On Hair and Tatter, Bristle, and Mend

Cultural anthropologist Paulette Young explores a Sonya Clark exhibition—as well as anthropological and personal reflections on hair.

Sonya Clark, Hair Craft Project Hairstyles (Ife), 2014, from series of 11 color photographs, each 28 x 28 in. On loan from the artist. © Sonya Clark. Photo by Naoko Wowsugi.

Tatter, Bristle, and Mend is the first mid-career survey of conceptual artist Sonya Clark’s 25-year career, on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, from March 3 to June 27, 2021. Clark builds on her knowledge and skill of fiber-art techniques and process to create mixed-media sculptures from human hair, thread, and the everyday objects and materials associated with hairdressing practice, such as combs, beads, cuttings, and currency, to comment on themes of identity, heritage, labor, language, and visibility. She weaves, folds, ties, braids, twists, rolls, wraps, rubs, dyes, and stitches these recognizable found objects to create artistic forms with new layered meanings that address, reimagine, and reassert race, memory, and belonging into our shared histories.

Tatter, Bristle, and Mend is a beautifully designed and thought-provoking show, housed in the landmark former Masonic temple. Delayed by one year due to the coronavirus pandemic, which disproportionately devastated my Black and brown neighbors, the show marked my first travel outside of New York City since the pandemic began. Feelings of grief and sadness along with the desire for and hope of rebirth accompanied me as I masked up and cautiously journeyed to DC.

As Clark reminds us, hair is a repository of our DNA that connects us to our ancestors and to each other. Hair and hairdressing are a major part of Tatter, Bristle, and Mend. She notes that while our texture and type may separate us, they also connect us: we are all tangled at our roots.

Hairstyling can mark a moment, celebration, or heartbreak. We dress the dead; we comb and style their hair to present them in a fine way for their final journey to the afterlife. Some communities shave their heads to symbolize mourning their loss, and for the Akan-speaking peoples of Ghana, traditionally the cut hair is piled at the entrance of the house in honor of the deceased. We save hair as a memento. My mother, understanding the power and history of hair, kept a lock of baby hair from all of my seven siblings so that she will always have a piece of us and our history through our hair’s DNA. In a similar vein, hair can also serve as a substitute for the physical body. I learned that for some Africans, when a relative died abroad, a tuft of hair or some fingernail or toenail clippings sent to the family was all that could be buried in the deceased’s home country. How might we use hair as a meaningful way to honor and memorialize our dearly departed and to heal our COVID-ravaged spirits?

These thoughts weighed on me as I came upon Pearl of Mother (2006) and Mom’s Wisdom or Cotton Candy (2011). In Pearl of Mother, a small, fragile hand sculpted of hair holds a delicate pearl shaped from Clark’s mother’s hair, a carefully constructed, beautiful treasure of a beloved and newly departed ancestor. It is juxtaposed with Mom’s Wisdom or Cotton Candy, a large portrait of Clark’s hands gently cradling a pure white puff of her mother’s hair. It is a sensitive homage, Clark notes, to preserve “the sweetness of her [mother’s] wisdom,” noting that, as the Yoruba peoples say, it is “when your hair turns white that your soul truly has become wise.”

As I moved through the show, what surprised me was the lessening of my anxiety and a growing feeling of comfort and nostalgia for home. Hair has played a significant role in my life. I was born bald and, much to the dismay of my mother, I remained so until the tender age of two, when my hair was finally awakened by natural oil massages, healthy foods, and hopes and prayers. I was subsequently blessed with a full head of black, richly textured natural hair, thicker than that of my three sisters.

On some weekends my aunts and cousins (real and play) would fill our kitchen with chatter about family, school, community issues, hopes, and dreams while our mother nurtured our hair. At the end she’d have created on each of us a virtual art form, a crown that celebrated Black womanhood. Today, I proudly style my wily tresses in a variety of braids, twists, knots, upsweeps, and the occasional Afro. Or, when I don’t want to be bothered, there is the snatch back, a simple style pulled back into a bun or chignon.

Sonya Clark, Fingers, from the “Wig Series,” 1998, cloth and thread, 10 x 14 x 14 in. Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, purchase through the Rudolph and Louise Langer Fund. © Sonya Clark. Image courtesy of Madison Museum of Contemporary Art.

Clark views hairdressing as the primordial textile art form. She notes, however, that “it’s not what’s carried on the head, but what’s inside.” Through my research, I have always been impressed by the rich array of African coiffure styles in field photos and present on traditional sculpture. One can identify a person’s ethnicity, gender, status, and phase of life development according to the type of hairstyle. Hairstyles in Africa are named, thus bestowing meaning and identity upon them, similar to other key objects, such as textiles, that mark important points in the life cycle.

Take Wig Series (1998), a collection of hairstyles made of thread on structured cloth forms. These descriptively named hairstyles—such as Crown, Unum, Hemi, Triad, Fingers, Spider, and Twenty-One—are reminiscent of the inventive ways that Black women create elaborate hairstyles to enhance their beauty, signify their status, and communicate power.

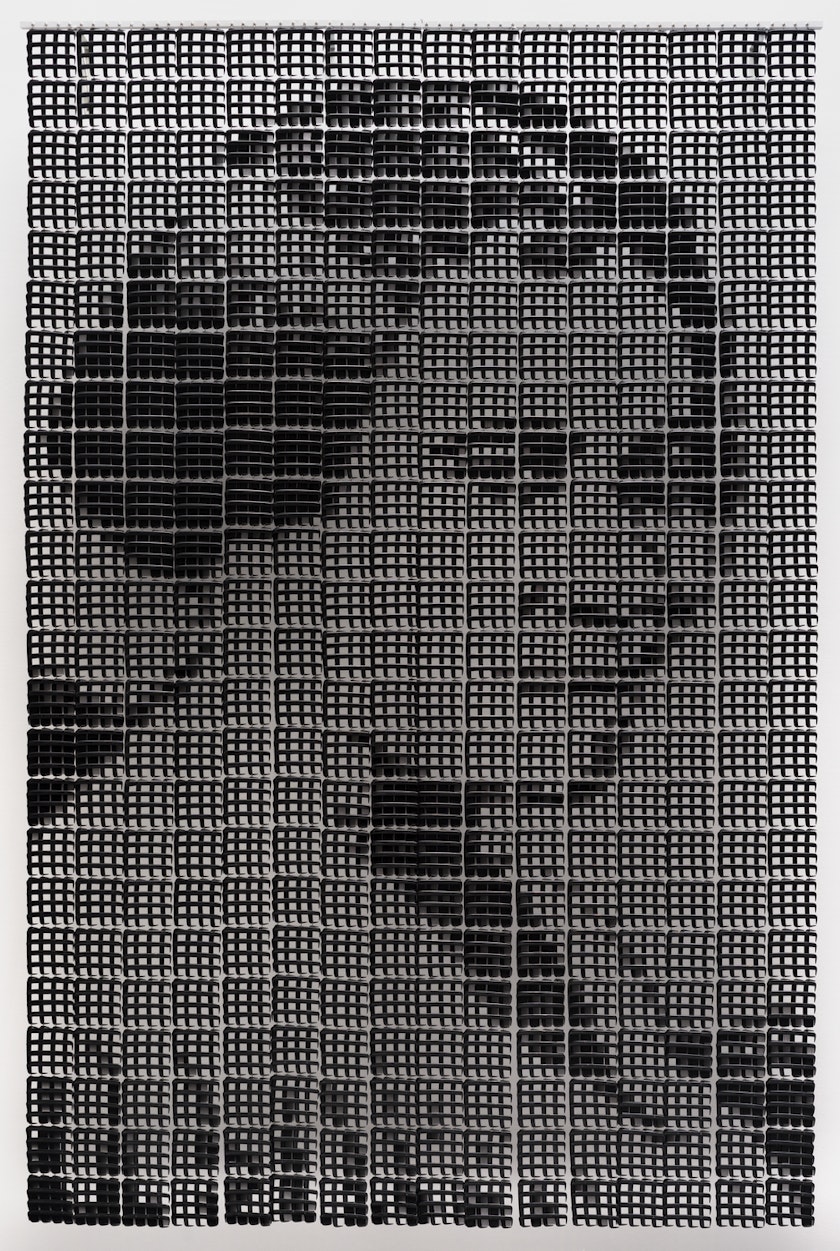

During my visits to the museum, I met various generations of Black women for whom the show resonated deeply. Many were from the DC area and came specifically and proudly to celebrate their local sister-artist. They were impressed with the creative ways that Clark transformed the comb, a primary tool for shaping the hair, into fine art and displayed it in a museum gallery. They took numerous selfies from camera phones with Madam C. J. Walker II (Comb Tapestry) (2019), a compilation of stacked combs that blend into a portrait of the African American self-made millionaire, philanthropist, and activist. Clark also uses a reductive technique, manipulating the teeth of the comb to create shading and to form patterns. In Kente Comb Cloth (2011), Clark uses black combs, offset by combs with colored spines and thread, to create a woven-like masterpiece that one would swear is an Ewe Kente cloth segment.

Sonya Clark, Madam C. J. Walker, 2008, plastic combs, 122 x 87 in. Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin, purchase through the generosity of Marilyn D. Johnson; Beverly Dale; Buckingham Foundation, Inc.; Jeanne and Michael Klein; Fredericka and David Middleton; H-E-B; Joseph and Tam Hawkins; Carmel and Gregory Fenves; The National Council of Negro Women (Austin Section); Lone Star (TX) Chapter of The Links, Incorporated; Town Lake (TX) Chapter of The Links, Incorporated; National Society of Black Engineers-Austin Professionals; Greater Austin Black Chamber of Commerce; National Black MBA Association Austin Chapter; and other donors. © Sonya Clark. Image courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art.

Despite the warnings I heard from other viewers on the danger of using human hair (It’s your energy, your DNA, and you can put “roots” on someone with it. That’s why you constantly sweep up the salon and the barbershop. You have to be careful.), it is the connection of hair to the body and to our heritage that calls out to Clark. She taps into the history of the movement of African peoples, from Africa to the Caribbean and to North America, to labor in sugar and cotton fields, and the making practices they brought along and developed. Triangle Trade (2011), a winding triangular cornrowed maze, juxtaposed with Sugar Eye (2016), a triangular framed all-seeing eye made of white sugar with an iris of rolled Black hair, depicts this history.

My mother, with familial roots in the rural Chesapeake Bay region of Maryland, wouldn’t allow us to wear certain hairstyles outside of the house. Braided styles like cornrows were associated with labor—unpaid work in the cotton fields during enslavement and slave-like wages for sharecropping arrangements in the Jim Crow South. Over time, the simple braid styles consisting of plaits and cornrows evolved to more complex designs.

A celebration of the skill and artistry of Black women’s hairdressing is on full display in Hair Craft Project (2014). Clark pays homage to 11 dynamic Black hair care specialists from Richmond, Virginia, with whom she collaborated to create original designs for herself. The oversized color portraits feature the artists with Clark as a model wearing their intricately braided styles. Clark notes, “The back of my head is evidence of their artistry.” In this way, she becomes their “walking art gallery.” This project is also a subtle monument to the labor of African American women in creating a wearable art form. I was particularly drawn to the image of Jamilah Williams’ floral pattern, which for me connects closely to the making of textiles, particularly the Yoruba adire eleko resist-dyed indigo cloth with its encoded meanings and messages. Williams’ design is akin to the cassava leaf Olokun design motif, named for the goddess of the sea and also associated with wealth.

Clark’s exhibition further explores the connection between hairstyling and textiles by highlighting the role of performance and participation to engage the audience in a complex dialogue on race. Clark introduces the viewer to the little-known Confederate truce flag, a basic white cotton cloth used by American Civil War troops to signal surrender. She contrasts this pennant with the Confederate battle flag in Unraveling (2015), in which she invites museum visitors to join her to deconstruct the battle flag thread by thread in a slow and methodical manner, similar to the communal practice of detressing braided hairstyles. Black women—some familiar, some strangers with a common goal—come together not to destroy but to detangle the coiffure strand by strand, reducing it to its basic form, and ultimately reimagining it as a new hair creation. In this communal practice, women share confidence in a fellowship that involves trust, care, and understanding. Similarly, participants in Unraveling are working shoulder-to-shoulder while unravelling the flag—often while sharing emotional reflections to the burden of America’s history of racial prejudice and injustice—and representing the painstaking work it will take to deconstruct long-held racial animosity in the United States. After the summer of 2020, with protests across the nation and world against racial injustice and the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other unarmed Black people, this performance is particularly poignant. Are we willing to deconstruct our past and weave a communal future that is just and inclusive?

Keep up on happenings in the craft world through our newsletter

Sign up to receive our Craft Dispatch, a curated dose of exciting events, opportunities, and content from our community delivered to your inbox each month.