Who's Afraid of Amateurs?

Who's Afraid of Amateurs?

Ask someone on the street about craft, and you’re apt to hear about yarn and glue guns, tie-dye and rubber stamps. This does not warm the hearts of professional craft artists and those of us who admire them. We tend to see a sharp distinction between the artists celebrated in this magazine and your average knitter or woodworker. We want the world to know there’s a whole other class of craft artist – not only highly skilled, but innovative and single-minded – that makes remarkable work in glass, clay, metal, fiber, and wood, among other mediums. Because we respect this professional artist so much, we may be wary of amateurs. We want people to know there’s a difference.

This impulse to distinguish between serious craft artists and their more casual counterparts is mirrored in the scholarly community. “The reality is that much craft scholarship, at least by art and craft historians, has focused on professional craftspeople,” says Cynthia Fowler, art historian and chair of the art department at Emmanuel Who’s Afraid of Amateurs? Why scholars – and all of us – should pay more attention to the work of non-professional artists. interview with Cynthia Fowler by Monica Moses College in Boston, whose research increasingly focuses on hobbyists and hobbyist practices. Scholars, Fowler points out, can be wary of amateurs, too.

This preference for the professional would make perfect sense if the boundary between amateur and professional were easy to discern and maintain. But it’s not. At what point does a backyard batiker become a professional? Is the threshold a matter of schooling? Making money? Time invested? There are acclaimed craft professionals who never went to art school. And there are artists with advanced degrees who can’t make a living. On top of that, there are part-time, self-taught artists who do extraordinary work. Suddenly, the categories become blurry.

It’s possible to identify differences between amateurs and professionals. But they may be subtle differences of degree rather than kind. After all, every professional starts as an amateur. The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

We consulted Fowler, who, with Susan Richmond of Georgia State University, is presenting “Amateur/ Professional: Reconsidering the Craft Divide” in October at the Southeastern College Art Conference. We asked her what makes a professional and why that seems such a thorny question.

In terms of how we observers tend to view craft artists, you’re either a professional, to be taken seriously, or you’re an amateur, and never the twain shall meet. It’s a professional/ amateur binary, rather than a continuum. Is that your experience?

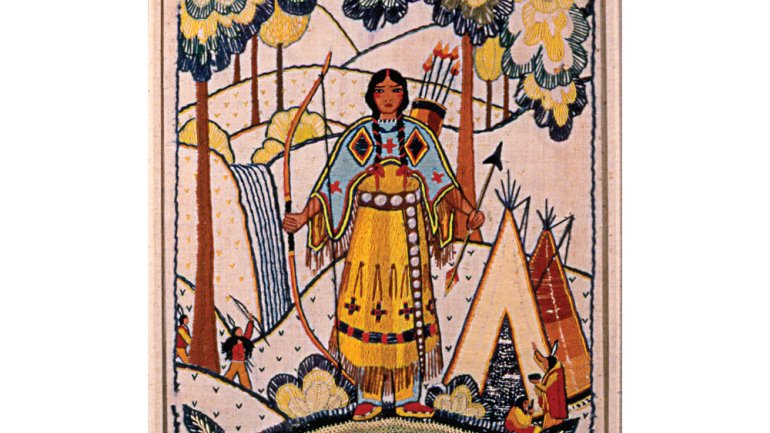

My own experience with the craft divide comes from my research on American artists experimenting with craft in the first half of the 20th century. The artists I have studied considered their experiments in craft, in which they were untrained, to be essential to their development as artists. Some of them ultimately gave up their painting practices and dedicated themselves exclusively to craft production. An example is Georgiana Brown Harbeson, who was trained as a painter but began making embroideries beginning in the early 1920s. She argued extensively throughout her career that embroidery should be viewed as art. She was more successful selling her embroideries than her paintings, so turned to making and designing embroideries exclusively.

Such artists who were not trained in craft might be considered hobbyists. But their art training resulted in their craft production being viewed as professional work. To your point that professional craftspeople and hobbyists form two distinctive groups: The question of training is central. What kind of training makes one a professional? Is it academic training at an art school? And at what point has a hobbyist, a self-taught crafter, developed enough in his or her craft to be viewed as a professional? Historically, these questions have been answered in different ways at different times.

Do you think the professional/ amateur boundary should be less rigid?

I’m not arguing that it should be less rigid. But I am raising questions about how this boundary operates to either include or marginalize certain groups of people from contributing to our understanding of the history of craft. The reality is that much craft scholarship, at least by art and craft historians, has focused on professional craftspeople. This is starting to change. Scholarly research on hobbyist craft will open us up to new perspectives on craft production as a whole.

The tendency to discount hobbyists is mirrored in the studio craft world at large. You don’t see this as much in the fine art world. I don’t think a weekend watercolorist is necessarily disconcerting to an acclaimed fine artist, but many in the fine craft world are leery of being lumped with Martha Stewart and scrapbooking. Why do you think that is?

I think this is because of the precarious position that craft has held historically in relation to [fine] art. Your question brings to mind the fiber arts movement of the 1970s. Fiber artists wanted their work to be evaluated in the same way that painting and sculpture were – as art. To ensure this, they could be quick to disassociate themselves from the long tradition of work in textiles by women untrained as artists.

What would the craft world look like if the boundary were less rigid?

For me, it’s not about blurring the boundary between professional and hobbyist craft so much as developing an understanding, both historically and critically, for both categories of craft.

That being said, we do need to consider what interests are served by maintaining a highly regulated boundary between the two categories – art-market interests, for one. And consider the ways in which women and artists of color have been excluded from recognition in the art world due to institutional biases that have prevented their full participation. Those same institutional biases are at work in restrictive definitions of art that position it as more valuable than craft. With a less regulated boundary, craftspeople who start out as hobbyists might be more easily recognized as professional when they develop their practices. And we can’t forget that several key contemporary artists – Tracey Emin and the late Mike Kelley are two examples – have appropriated hobbyist craft as a mode of artistic expression.

Do you think that people in the studio craft world would be unsettled if the boundary were blurred? If so, why?

I hope not. Why would they – out of fear that their status might be undermined? I respect those fears, considering the historical conditions that have undermined an appreciation for craft. But I hope that they can be assuaged by more serious analysis of the craft tradition. Hobbyists and studio craftspeople share an interest in an important form of creative expression. They share a love of materials and the possibility of exploring their full creative potential. That they engage in creative expression in different ways should not undervalue one group or the other.

In current ways of thinking about craft amateurs and professionals, what constitutes a professional? Many acclaimed craft artists (e.g., Lino Tagliapietra, often called the world’s greatest glassblower) don’t have BFAs or MFAs. So is professionalism a matter of being able to make a living as an artist rather than having a certain type of training?

I think it’s a matter of the types of dialogues a person might engage in their craft. Some selftaught artists have developed a craft practice that affords them a good living, while many professional craftspeople can barely get by selling their work. Craftspeople who achieve the status of Tagliapietra do so in part because they engage questions in their work that interest the world of art and of craft.

I’d suggest that hobbyists are engaging different questions, but these questions are equally interesting, and this is just beginning to be recognized by scholars. I’m thinking of embroidery hobbyists who add familial symbols, like a favorite chair or the family pet, to a standardized pattern they have purchased. Hobbyists may also be more engaged in local trends than global ones when making their work. Their creative community might consist of neighbors and friends rather than less personally connected participants in an international biennial, for example.

Hobbyists can often engage questions of interest to the art and craft world as well, but this, too, has yet to be fully explored by scholars.

If amateur/professional is not a fruitful way to describe the distinction, what would be? Beginner/advanced?

Rather than coming up with another binary, I think the goal is to consider these categories historically and how they operate to create hierarchies. All makers start at some beginning in their practice and develop or advance over time. Most important is to examine all types of craft production with consideration of points of convergence and departure, without making value judgments about which type of craft is more significant than the other.