Crafted stories.

Every object has a maker, and every maker has a story. Discover the narratives of emerging and established artists, the evolution of their creations, and how the everyday is made more extraordinary through the fine art of craft.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

280 articles

-

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadThe Queue: Felicia Greenlee

Felicia Greenlee carves and chisels images of social change in her layered narrative wood collages. In The Queue, the Seneca, South Carolina–based artist shares about the craft community in South Carolina, the skills she gained as a textile designer, and a traveling exhibition featuring her work.

Digital Only

The Queue -

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

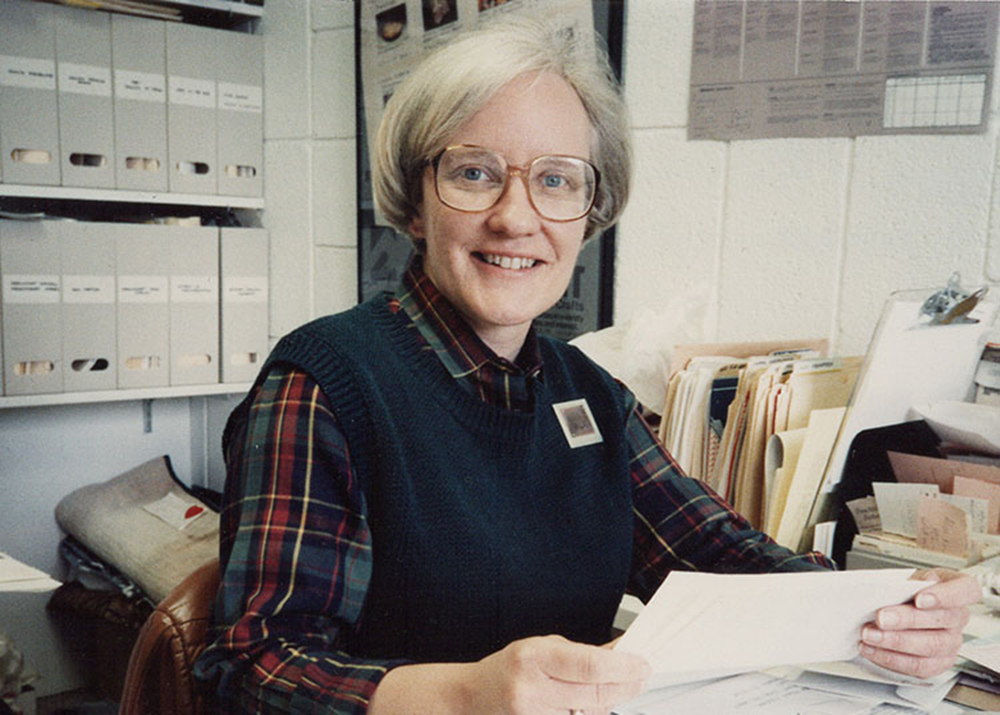

ACC NewsFree To ReadRemembering Sandra Blain

ACC Honorary Fellow Sandra Blain passed away on December 19, 2024. A multi-faceted leader in the craft community as an educator, administrator, and ceramic studio artist, she had a long-time relationship with ACC.

Digital Only

-

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadThe Queue: Nosheen Iqbal

Nosheen Iqbal foregrounds Pakistani and Islamic art in her entrancing embroidery-on-wood compositions. In The Queue, the Dallas-based artist and designer chats about CraftTexas 2025, developing clients in the corporate and hospitality worlds, and two contemporary events pushing Islamic and South Asian art forward.

Digital Only

The Queue -

![Patterned ceramic cups and plates]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadI Love Pots

A studio potter and the founder of @nonclaypots and @potterytattoos writes about how and why she began sharing her passions on social media.

Digital Only

Essays -

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadThe Queue: Samantha Briegel

Samantha Briegel’s fashion-inspired porcelain vessels dazzle with patterns and textures. In The Queue, the Maryland-based ceramist talks about how she creates her work, her favorite slow fashion designers, and what she’s looking forward to at this year’s American Pottery Festival in Minneapolis.

Digital Only

The Queue -

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadCouture Craft

A new nonprofit, Closely Crafted, advocates for skilled makers in the fashion industry.

Fall 2025

Craft Communities -

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

ACC NewsFree To ReadMN State Fair 2025

The Minnesota State Fair is here! Each year, the American Craft Council is proud to give an award to an entry in the Fine Arts category that exemplifies craft. This year, ACC is pleased to give the special recognition to Iah Q’s The Past Holds Me, a stunning work of beadwork on leather.

Digital Only

-

![Metal handbag created by Bliven for Tory Burch]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadRunway Ready

Metalsmith Thomas Bliven crafts handmade accessories for top-tier clothing labels and the celebrities who make their fashions memorable.

Fall 2025

Features + Profiles -

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadThe Queue: Dawn Williams Boyd

Dawn Williams Boyd fashions recycled textiles into powerful paintings in cloth. In The Queue, the Atlanta-based textile artist talks about her family’s dedication to the handmade, the extensive list of tools that make her work possible, and the importance of senior art programs.

Digital Only

The Queue

Story categories.

-

Craft Happenings

Browse a timely, curated, and frequently updated list of must-see exhibitions, shows, and other events.

-

Points of View

Essays, craft histories, ideas, analysis, and other perspectives on the significance of craft.

-

Makers

Profiles, interviews, studio tours, and videos on people who are making the world more beautiful.

-

Materials & Processes

Learn about materials and how craftspeople transform them into functional and sculptural works.

-

Handcrafted Living

Discover practical and pleasing handmade goods and stories about living with meaningful objects.

-

Travel

Explore the world of craft by visiting the places and communities where it is created and celebrated.

-

Media Hub

Discover new books, niche periodicals, videos, and podcasts—plus highlights from ACC’s archives.

-

ACC News

Explore the impact of the American Craft Council and the ACC community through stories and updates on our programs, events, artists, and more.

Take part.

Become a member of ACC.

Craft is better when we experience it together. Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and explore the nationwide craft community with a membership to the American Craft Council.