Risky Business

Risky Business

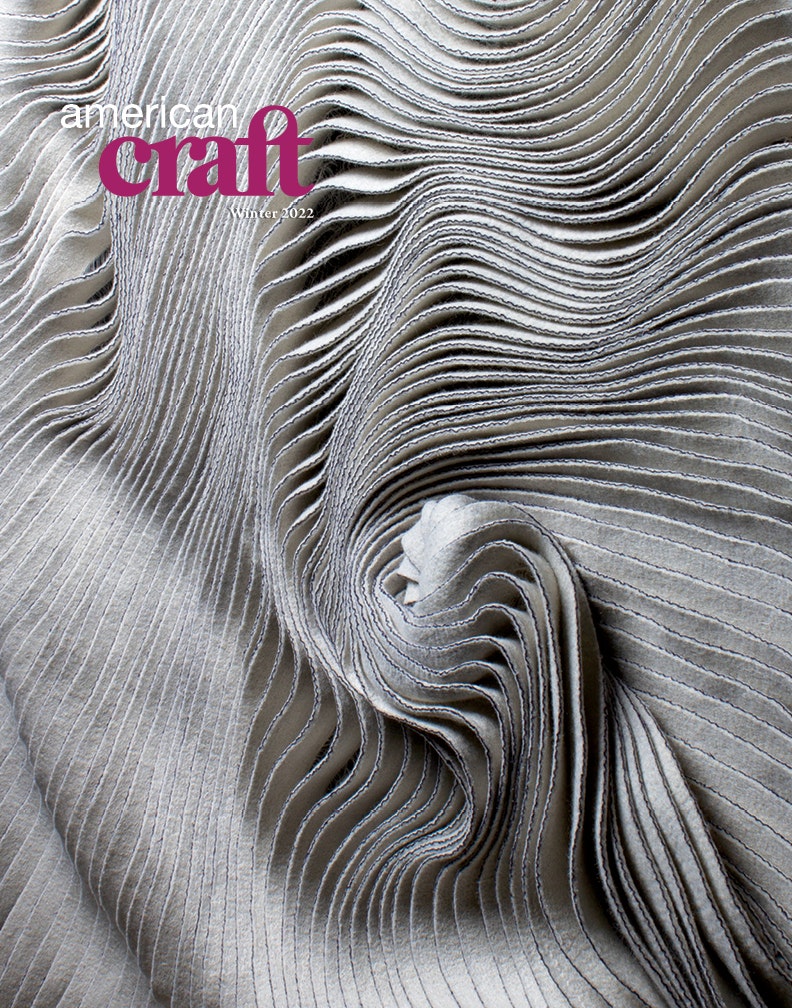

Ceramic artist Kevin Leiva, who lost his entire studio in 2016 during the wildfires that swept through Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, demonstrates his resilience (and humor) as he gets back to work. Photo courtesy of CERF+.

And those were the good old days. With the arrival of piecework and mechanization, craft trades were disrupted in an unstoppable wave. Cobblers were forced into divided labor. Seamstresses sat all day in front of sewing machines, making the same garment over and over again. Eventually, blacksmiths saw their shops converted to automotive garages. Through it all, artisans’ wages gradually declined, along with their autonomy. And as one might expect, the worst was borne by immigrants, ethnic minorities, and women, many of whom were not even recognized as professionals, whatever their level of capability. This is the ever-present backdrop of American craft history, though you wouldn’t necessarily know it from our nation’s museums or, indeed, the typical issue of this magazine. There’s an understandable tendency to focus on more positive narratives of revival and renewal, creativity and community. Those stories are important and inspiring, to be sure, and they should absolutely be told. But it’s always worth remembering that most craftspeople—throughout American history—have had precarious livelihoods.

This brings us to the word precariat, which has been making the rounds (though coined by French sociologists back in the 1980s, it has only entered general use in the past decade). A combination of precarious and proletariat, it refers to members of the working class who are highly vulnerable to economic risk and lack a safety net for their livelihoods when misfortune comes. The term has gained traction recently because of the rise of the so-called gig economy, which leaves even more people without the infrastructure of regular salaries, insurance, parental leave, and pensions.

When it comes to craftspeople, as I’ve just said, these dynamics are nothing new. As independent operators, they have always striven for self-sufficiency, which is a terrific thing—until it fails. Earlier this year I published a book called Craft: An American History, which recounts the story of the nation through the eyes of its makers. That project helped me see just how tough the artisan’s lot has often been and further increased my respect for those who have prevailed against the odds. It also made me want to better understand the current state of the craft economy—which has been massively disrupted yet again over the past two years, of course, along with just about everything else. Is it right to think of makers as part of the contemporary precariat? If so, how should that affect the way we think about craft and its cultural position?

Big questions. Fortunately, I knew just whom to ask: Cornelia Carey, the executive director of the Craft Emergency Relief Fund, known familiarly as CERF+. This vital organization was established in the mid-1980s by glass artist Josh Simpson and art fair director Carol Sedestrom Ross, with support from a group of like-minded craftspeople. These founders had seen too many of their colleagues experience economic distress, for all kinds of reasons—a fire or flood, a theft of work or equipment, or a personal health crisis. While the craft community was often generous in such circumstances, the “pass the hat” model was obviously inadequate. They resolved to do something about it.

Is it right to think of makers as part of the contemporary precariat? If so, how should that affect the way we think about craft and its cultural position?

Carey, who has a background as a state arts grant administrator, is marking her 25th anniversary at CERF+ this year. Over this time, she has seen a lot of change. (“For starters,” she laughs, “my hair was brown when I started.”) The organization has grown considerably, broadening its mission in response to need. Its origins were in the American Craft Council’s fairs, and its demographic was largely made up of white studio craftspeople, based mainly in the Northeast. The organization has since broadened its scope considerably, reaching an ever more diverse population. Today, the recipient of a CERF+ grant is just as likely to be a “folk” or vernacular maker, and the organization is active across the US and its territories.

With this expansion, Carey and her colleagues had to think hard about the tricky issue of merit. When working across such a varied field, linking aid to qualitative assessment is certainly difficult, and perhaps irrelevant. When COVID hit, the organization amassed a pool of nearly $1 million in emergency funds. Eligibility was based on dire need, such as food, housing, or health insecurity; Black, Indigenous, and people of color as well as folk and traditional artists were prioritized for support. Grants were awarded based on a lottery system, rather than some subjective, quasi-curatorial evaluation process. Given such policies, it may be that CERF+ is the most genuinely egalitarian craft organization in America.

At the same time, it has undergone a steady process of professionalization and expertise-building. Carey saw immediately that direct aid in the wake of a disaster, while crucially important, could not hope to meet the scale of the need. “No amount of money we could raise will help all the people affected right their lives,” she says. Accordingly, she began to focus more on planning, preparedness, and mitigation. CERF+ now concentrates on helping craft makers connect with bodies such as FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency), assisting them in navigating the mazelike bureaucracies of governmental bodies and insurance companies.

This distinctly nonglamorous work has become even more important given the steady increase of weather-related tragedies that afflict the United States. (Carey pointedly does not refer to them as “natural disasters,” because they are so entangled with human-induced climate change.) If a full history of CERF+ ever gets written, its milestone events will be hurricanes: Katrina in 2005, which got the organization involved with craftspeople in the Deep South; Maria, which devastated Puerto Rico in 2017; and Ida, which was unleashing its destructive force just as I was writing this article, flooding homes and studios from Louisiana to New Jersey. When responding to such large-scale tragedies, Carey says, money isn’t always the most important thing. It can sometimes be important just to witness what has happened, affirming to those affected that they are not unseen, and to continue providing practical advice months or even years later, when the news cycle has moved on.

Given all this, you might think Carey would be quick to affirm that the craft community is firmly within the precariat. But when I put the question to her, she wasn’t so sure. It’s true, she said, that even leading makers—including some National Heritage Fellows, who have earned the highest form of recognition given by the National Endowment for the Arts—are often “one calamity away from total silence.” Yet craftspeople are also remarkably able to rebound from a crisis. Firmly rooted in their communities, they almost always are able to find new ways to flourish. (It’s not a coincidence, Carey observes, that so many are gardeners.) Given a little assistance when they need it, craftspeople can usually regain their economic equilibrium, and these success stories are a big part of what makes her work with CERF+ so fulfilling.

For all the forces arrayed against them, it’s amazing how resilient artisans have been over the course of centuries, readily adapting to adverse circumstances.

This is a very different picture from the precariat as it’s typically understood by economists: a seemingly permanent underclass with little hope for stability. The British social theorist Guy Standing, who helped popularize the concept (and also accurately predicted the rise of right-wing populism in America and Europe) in his 2011 book The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, says that members of the precariat “lack an occupational identity or narrative to give to their lives.” This begins with a lack of educational opportunities, leading in turn to part-time, informal, or insecure jobs. In Standing’s analysis, one of the biggest problems for those trapped within the precariat is simple uncertainty: they must spend their time hunting for work, constantly retraining, and often coping with transient housing.

The situation for craftspeople is just the opposite. They have already put in the time to learn their trades. They know exactly what they need to do, and how. Their firm sense of identity is rooted in skill, which can be brought to new workspaces and applied to new products, materials, and markets, all without losing the essence of the craft. All this means that makers are able to achieve stability on their own terms, if their lives aren’t disrupted. And all this provokes an interesting thought. Craft makers find themselves perpetually situated at the edge of precarity, but they also have the means to escape the vicious cycle that traps so many people in low-income “McJobs.”

So maybe craft is actually a way to stay out of the precariat. This argument certainly resonates with my research into American history. For all the forces arrayed against them, it’s amazing how resilient artisans have been over the course of centuries, readily adapting to adverse circumstances: think of quilters, making do with scraps from home dressmaking, or woodturners, employing the offcuts of lumber factories.

Thinking through craft in relation to the precariat puts a new spin on some familiar themes: the 19th-century myth of the “self-made man,” the Arts and Crafts Movement ideal of “joy in labor,” the postwar trend to “do it yourself.” As the world of work becomes increasingly disjointed, these long-established notions of dignity and self-reliance are infused with new urgency. This is partly about actually making a living with one’s hands. But craft is also a powerful symbol, infused with proud individualism and community spirit, long-held values that the gig economy threatens to erode. As America pivots swiftly toward atomized opportunism, it looks as if more and more people will have to go it alone. A career in craft is indeed a fragile thing. But in an uncertain world, it may also be one of the strongest remaining foundations for a functioning society.

Discover More Essential Articles in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and gain the perspectives of the artists, writers, and community organizers who are moving the craft field forward.