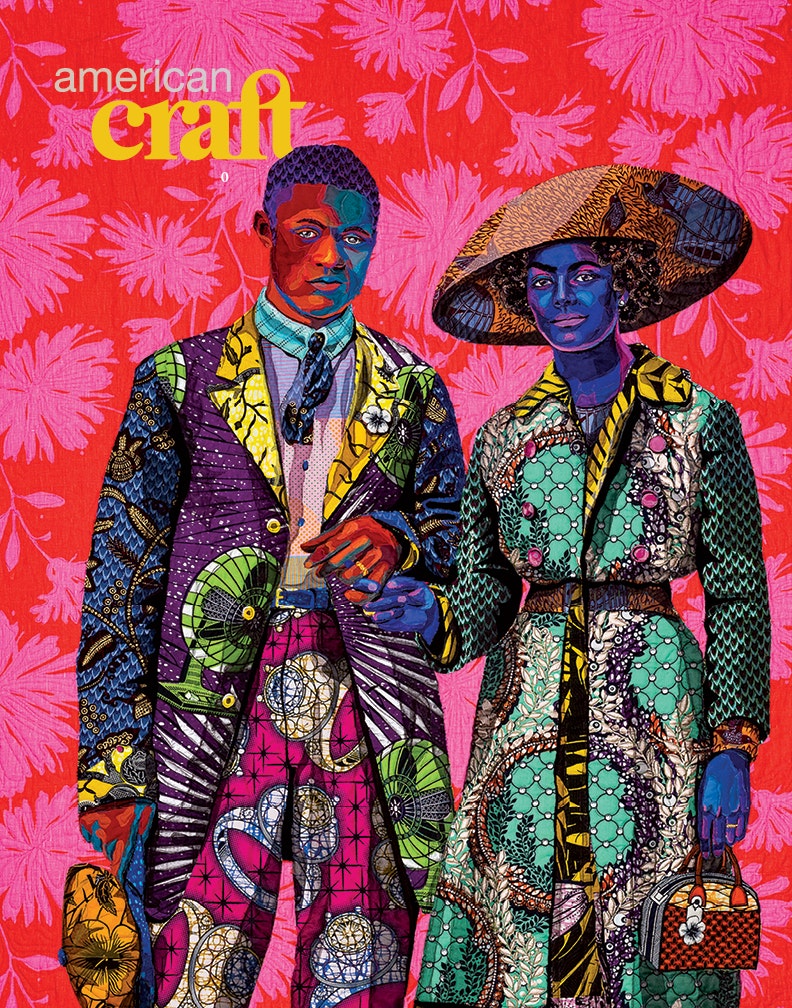

The Energy of Kinship

The Energy of Kinship

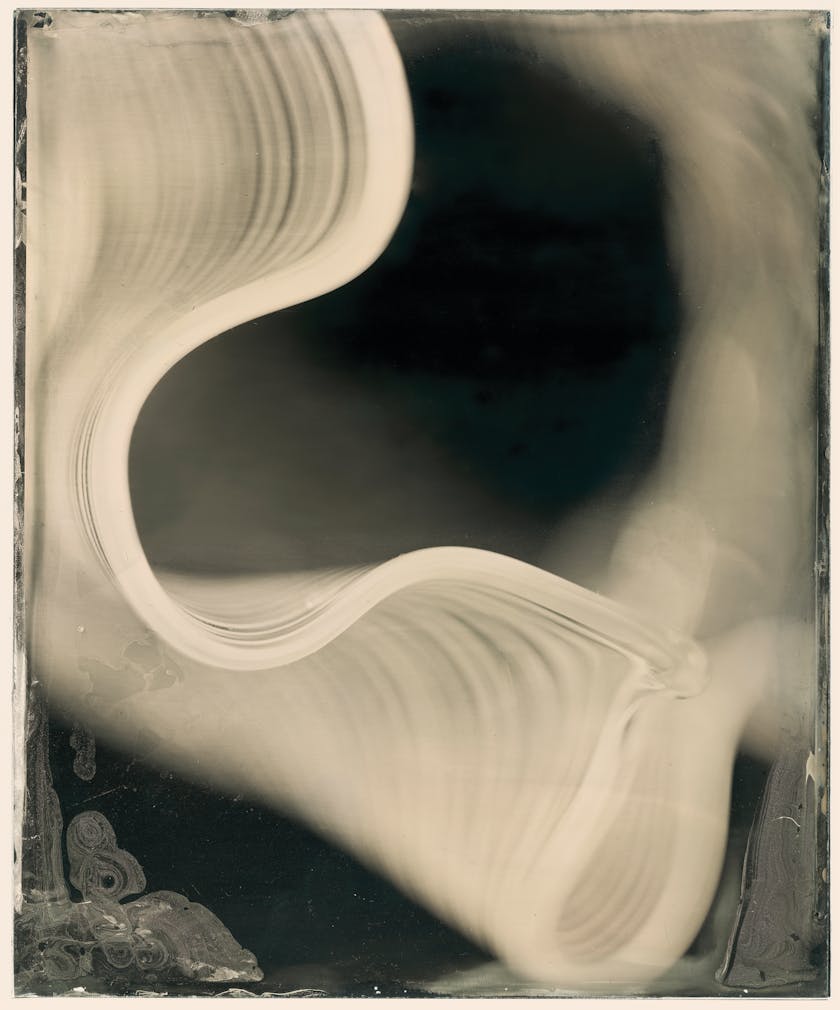

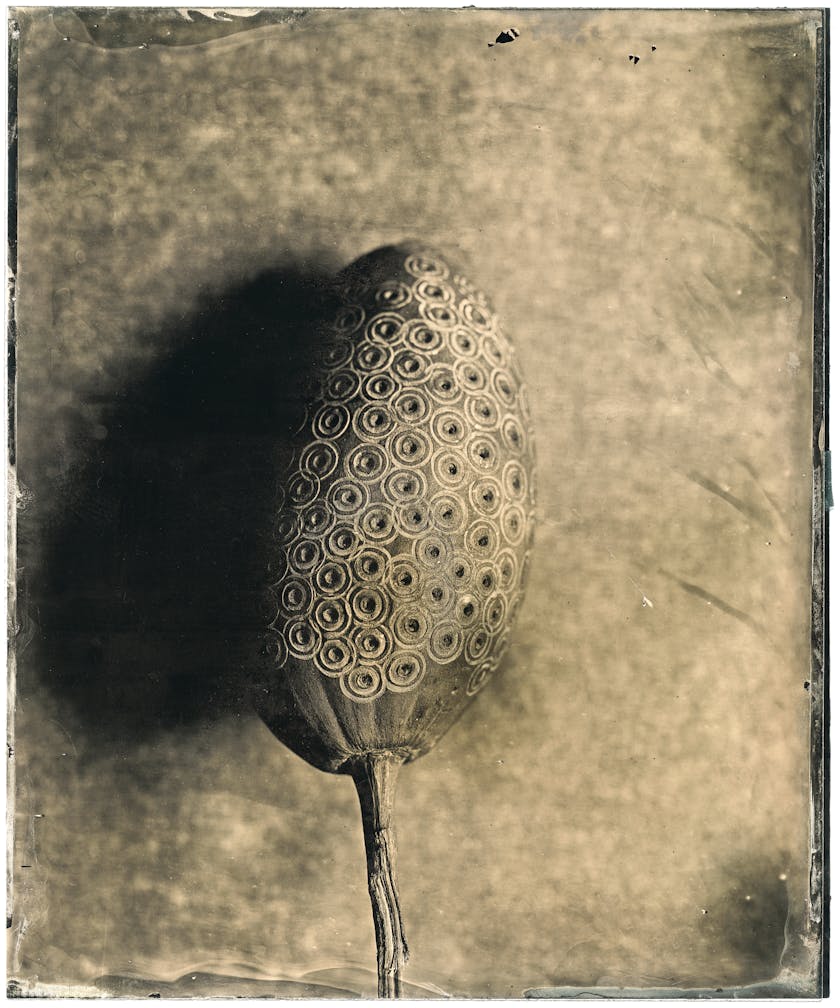

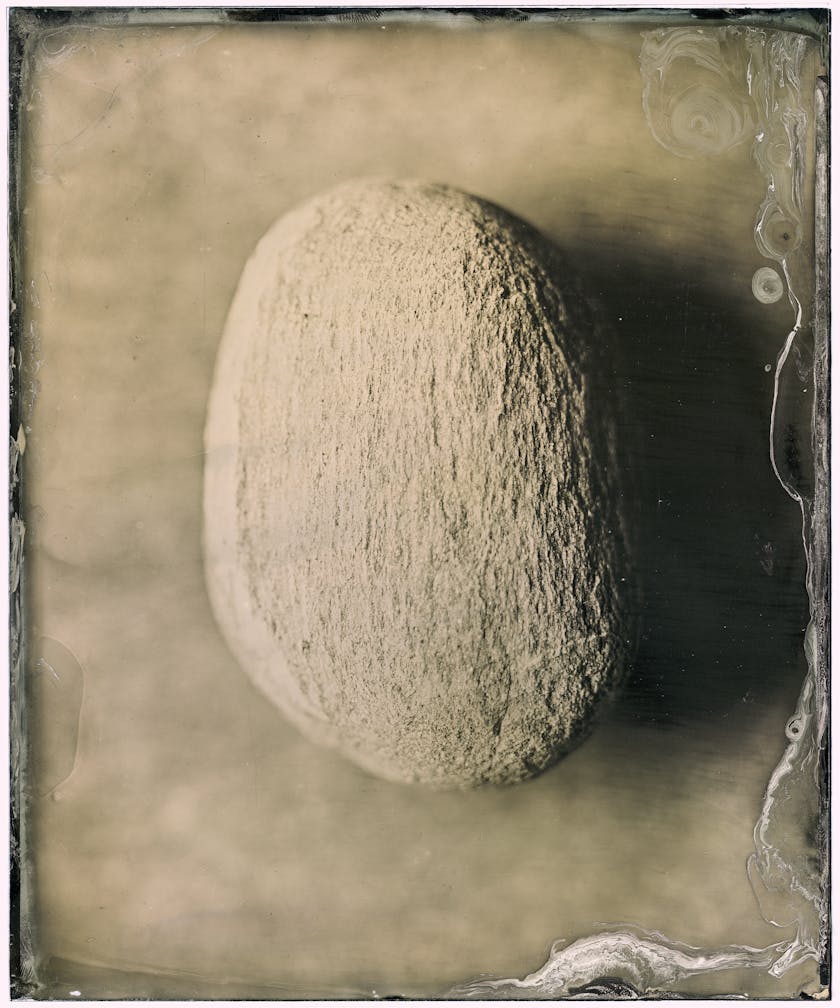

The images accompanying this article are collodion wet-plate photographs by Daniel Costa, who was assisted by Sylvain Belan and Henri Gaud.

Lidewij Edelkoort is one of the world’s most respected cultural forecasters, consulting for international companies in diverse industries. She is also a magazine publisher, a design educator, and an exhibition curator. Edelkoort is one of the founding members of Heartwear, a not-for-profit organization based in Paris that has worked with artisans in Benin, Morocco, and India since 1993. In 2015 her much-talked-about Anti_Fashion Manifesto was the first to raise awareness about the shifts and upheavals currently experienced in the global fashion industry, calling for a total overhaul of the system. Edelkoort is also the founder of New York Textile Month, and from 2015 to 2020 she was dean of Hybrid Design Studies at Parsons School of Design in New York, where she started an MFA textile program to merge craft and tech for a sustainable future. She received a Lifetime Achievement award from Aid to Artisans in 2005 and was honorary chair of the International Folk Art Market in 2017. Her recent book A Labour of Love, co-authored with Philip Fimmano, introduces the new makers in contemporary design, previewing an era of responsible production, circular thinking, ethical practice, and organic aesthetics. Edelkoort’s work as an agent for change culminated in the founding of the World Hope Forum in 2020 as a platform to inspire the creative community to build a better society.

The renewed understanding that we are all sentient beings connected us in a natural way, bringing the revival of animism to the fore, recalling the earliest primitive rituals and belief systems that came before organized religion, such as the veneration of the forest and the feather, the river and the pebble, the shadow and the twig, the flower and the animal. Many of these traditions are still alive and well in heritage cultures around the world.

Photo by Daniel Costa assisted by Sylvain Belan and Henri Gaud.

The term animism speaks of life and spirit. It is the belief that all objects, places, and creatures have a spiritual energy, and that all things are vibrant and alive. This idea breathes life into the ability of humans and nature to live as one. In modern society, people talk to their cats and cars as if it were normal. They sleep with their teddy bears, nurse their plants, and worship their phones like amulets. This is basic animistic behavior and invites us to further investigate the relationships we can foster with all other entities.

At the core of contemporary animism is a current strain of philosophy that acknowledges how all materials are powerful and energized, possessing their own properties and rights, just like animal rights and human rights. When we discover this other world, removing people from the center and instead sharing mental and physical space with unfamiliar forms of life, this brings a sense of belonging, opening up a flow of energy and unleashing positive unknown forces.

Photo by Daniel Costa assisted by Sylvain Belan and Henri Gaud.

New animism translates this connected view of the world into a form of unnovation, where proven ancient rites, rituals, objects, and beings form a vital kinship, rejoicing in what we have in common and revering the ecology of multiple selves. Relations are defined by a quest for organic wholeness, in stark contrast to the modern notion of separating nature and humans. In a world no longer divided between nature and culture, where we can discern art within a single seedpod or find instinct in humans, we long to unite these two spheres and can see our role as creative partners with the amazing natural world. Such assemblages of objects and beings will redirect the organic evolution of society and begin the healing process of reconciliation.

This newfound respect for nature and deeper understanding of the energies that abound will shape another way of designing and making, slowing down and taking time for observation, acknowledging the dynamic character in the product, object, or textile. When we create common relationships with the material world, seeing the living identities in things, we will also experience social obligations when engaging with these animated bodies. Receptive and communicative, they are able to create a dialogue with their public.

Photo by Daniel Costa assisted by Sylvain Belan and Henri Gaud.

Objects can survive in the jungle of excess, and their animistic spirit will bring solace to our interiors, where fewer products will wield more potential. With deities empowering objects, the role of the designer or artisan will change, based on observation and empathy. By conceptualizing the emotional value of goods, our culture can convey the ardor inherent in everyday items, to be contemplated in a consoling environment. We will thereby intuitively regulate overconsumption and the waste in the making process.

Born after the Second World War and raised during the years society was rebuilt, I enjoyed a simple youth without having anything at all: minimal food and only one toy, a box of colored pencils, and a sketchbook. Children had to invent their own world from scratch, or, as in my case, create everything else from cardboard. There was only one car on our street; it was my father’s, and this made him the local hero.

Following that very happy and creative childhood, I lived through decades of more and mediocre, of more and better, then more and more, and then more and too much. I have witnessed and participated in the birth of lifestyle, the advent of well-being, the democratization of taste, and the obsession of food and fashion. Soon, half a century will have passed before my eyes and ears as a forecaster.

The explosion of creativity that will result . . . could become the cornerstone of a new arts and crafts society.

Witnessing ever-fluid sociocultural scenarios in our post-virus landscape, it is clear we have to modify our unsustainable behavior patterns and choose what will promote the survival of our species—and that of our planet. We will focus on having less and doing better and living slow. An evolution of taste will see the light of day, one that will search for the soul in design, where the object—conceptualized with care and focus, manufactured with human dignity, and consumed with joy—becomes a partner for the long term.

An alternative way to describe design is form-giving—as we say in Dutch—which is a beautiful term since it includes the powerful notion of how talent and skill can create a sense of wonder. With the arrival of animism in products, we can reach another stupendous conclusion and realize that form is not given but found. Shapes can be born out of observation and interpretation, where a humble pebble becomes a trustworthy stool, a cloud is seen as a welcoming textile, a twig turns into an endearing chair, and so forth. Leaves translate as arts and crafts, feathers into fluttering fibers, roots become agrarian matter. Simply picking up an ornamental shell can be a creative act of form-finding, where the undulating creature can inspire objects, buildings, textures, and finishes. If we can imagine shapes in clouds and see spaces in between boulders, the exciting world of form lies before us.

Photo by Daniel Costa assisted by Sylvain Belan and Henri Gaud.

Perhaps we need to revisit the beginning of time and meditate on what the planet’s original peoples knew. Their wisdom and strength have been kept alive for centuries and are able to teach us new practices for age-old systems: overhauling the modern idea of progress, making space for ancestral architecture as well as sustainable manufacturing, farming, and fishing. Indeed, from farm to furniture, the harvest should now be related to production limits and the careful calculation of available resources. At times, the land needs to rest, and the forest needs to breathe, and we humans should wind down too, taking a break from consumption.

Here, the designer, artist, and artisan are all one and the same, and the making process guides the outcome that can be random and uncontrolled. Giving up control, with wilder grasses, bolder baskets, robust plates, and frilled fabrics. As if willing it, the explosion of creativity that will result from these innovative ways could become the cornerstone of a new arts and crafts society in the making.

It is time to recognize in goods their own character, an invisible energy locked into the design process. I believe this will allow the object, concept, or service to come alive to be our partner and friend, and to relate to us on a direct and day-to-day level. Only when emotion is central to design and craft will we be able to create a new generation of things that promote and sell themselves; we will have helped reveal their aura, which will seduce even the most hardened consumers on their own terms. Only then will more of us see that objects have soul.

Discover More Inspiring Articles in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine to stay in touch with our ever-evolving craft movement.