The Future of Craft Collecting

The Future of Craft Collecting

Cheech Marin (center), one of the world’s foremost collectors of Chicano art, with Einar de la Torre (left) and Jamex de la Torre (right) at The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture at the Riverside Art Museum in California, which opened June 18, 2022. Photo by Carlos Puma, courtesy of The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture at the Riverside Art Museum.

In America, many of the earliest craft collectors were inspired by the 1969 traveling exhibition Objects: USA, a show that epitomized the trend of craft as fine art. Helen Drutt English opened the first craft gallery in Philadelphia in 1973. Around the same time, the American Craft Council shows played a significant role in the early development of the craft economy. (Read more about the history of ACC’s shows in the Summer 2022 issue of American Craft.) Buyers were drawn to the unique creativity of craft art, and they appreciated the approachability of its scale, familiarity, and affordability.

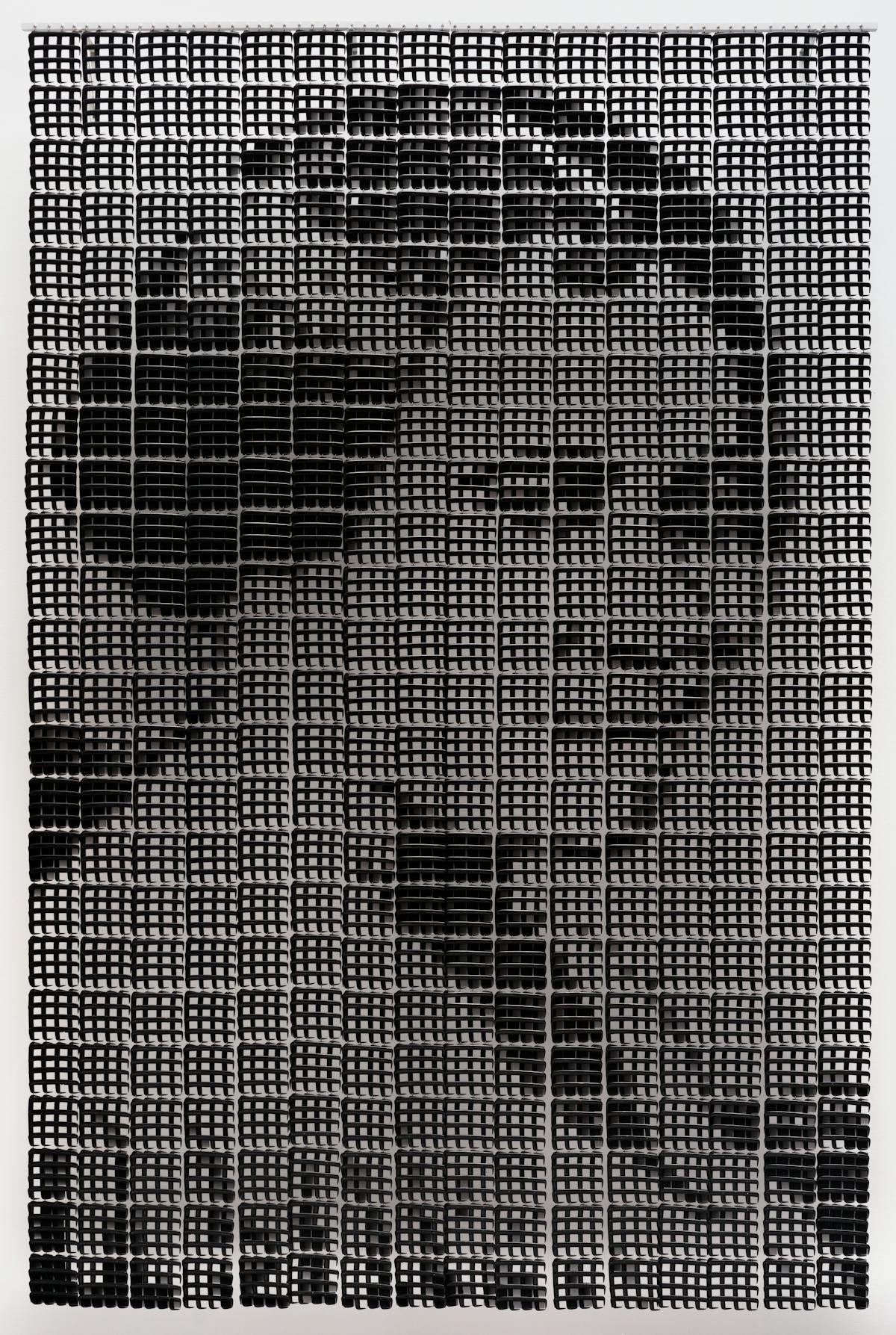

At The Cheech Marin Center's entry is a 26-foot-tall lenticular artwork by the de la Torre Brothers. It features an image of the Aztec earth goddess Coatlicue. When viewed from the right angle, the image changes to a Transformer-like robot made of lowrider cars. Photos by Carlos Puma, courtesy of The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture at the Riverside Art Museum.

Craft collecting reached its height in the 1980s and early ’90s. Contemporary craft galleries proliferated in American cities, and as craft became more popular, prices increased and the boundary between art and craft blurred. Many collectors continued to support the artists as traditional patrons, buying new works, offering lodging when artists were in town, and forming lasting friendships. Conceptual artwork, ephemeral objects, installation, performance, and artwork later known as “craftivism” were popularized in the 1990s. However, in the early 2000s, independent (“indie”) artists led a return to functionality. They created useful items with a DIY aesthetic, to engage a new generation of socially conscious buyers.

Early collectors are now in the process of deaccessioning their collections via gifts to institutions or sales through galleries and auction houses. Securing the placement of a piece in a major museum can elevate the value of the artist’s work, with ripple effects benefiting other artists in the same medium, other works in a collector’s roster, and the field at large. However, museums are now taking a harder look at what their institution’s collection will say to future generations about the craft movement and the society at large. For example, the coveted Renwick Gallery recently added almost 200 craft works to its collection, but only about 10 percent of the works offered by collectors were accepted. Donors may instead choose to increase public exposure to craft by giving to less obvious public institutions, such as smaller museums, colleges, hospitals, or large encyclopedic museums that lack American craft. Additionally, the influx of works into the market will be a benefit to new collectors who will now have access to high-quality works.

The future of collecting is now poised for a reimagined revival. As craft evolves with new mediums, concepts, and artists, so does collecting. Contemporary trends and exciting innovations suggest a more accessible, democratic future where collecting can be a force for change.

Louise Rosenfield donated a large portion of her collection of 4,000 handmade mugs to the Everson Museum of Art with the stipulation that the works be used. Pictured here (top to bottom) are mugs by Kari Radasch, Pattie Chalmers, Akio Takamori, Naomi Clement, Beth Lo, and Calvin Ma. Photos courtesy of the Everson Museum of Art.

1. Reframing Who Is—and Can Be—a Collector

Art history has long painted collectors as gatekeepers and authorities of taste. For centuries, collecting has symbolized colonial looting and the dominance of wealth within societies. However, this outdated mindset doesn’t encompass the array of steadfast supporters and collectors of the craft field today. Recently three next-generation craft collectors were interviewed for the James Renwick Alliance for Craft’s Craft Quarterly. It was made clear that deep-rooted elitist stereotypes about collecting, a lack of transparency about the collecting process, and dated authoritarian narratives are hindrances to a new generation of buyers and others who seek a more inclusive future. Reframing the notion of what a collector is may be the biggest challenge craft collecting has to face.

Serious collectors in the craft field are very welcoming and have dedicated a major part of their lives to learning about craft, supporting artists, and promoting organizations that advance the field. Because the studio craft movement was founded in defiance of commercialism, buyers of craft have always made a statement with their purchase, whether intended or not. Instead of buying mass-produced objects, they invest in an artist’s future, thus defining their aesthetic and social priorities.

A new generation of collectors has emerged, and their interests are as diverse as the collectors themselves. Some embrace the socially conscious aesthetic of the DIY movement by filling their homes with handmade objects. Other new collectors see no difference between art and craft and purchase conceptual artwork that’s based in a range of craft materials. When a craft collector is understood as a person who prioritizes the purchase of craft art, collecting ceases to be for a select few and is open to everyone who wants to make a difference in the field.

An innovative example of collecting and donating according to one’s personal convictions is the Rosenfield Collection. Louise Rosenfield is an avid pottery collector who began by purchasing a humble handmade mug and has since developed a collection of more than 4,000 pieces. As a proponent of the functional value of her vessels, Louise recently donated a significant part of her collection to the Everson Museum of Art with the stipulation that the works must be used and enjoyed daily. Soon, a new Everson Museum café will open where you can drink or eat from these superb pieces made by international artists.

2. Increased Access to Craft Art

Traditionally, a buyer would purchase an artwork in one of two ways:

On the primary market: buying directly from the artist or on consignment through a gallery.

On the secondary market: buying from a former owner through an auction house or gallery.

Large craft shows have provided easy ways to learn about and purchase craft art. However, first experiences in the field can also be convoluted or intimidating due to an unwelcoming gallery owner, buyer insecurity, or seemingly unobtainable price points.

One of the most interesting trends that breaks the mold of the art market is crowdfunded museum acquisitions. Madame C.J. Walker, a portrait by Sonya Clark made entirely of black hair combs, was acquired in this way for the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas. Marilyn Johnson, a docent and local Black businesswoman, led the initiative to purchase this work of art to ensure representation in the museum for other women like her. She raised the funds with the help of the museum by reaching out to other Black business owners in the community and ultimately secured more than 50 private donations to purchase the piece.

In the past two decades, buying opportunities and points of entry into the craft market have multiplied through social media platforms, significantly influencing the way people buy. The growth in the online art market has largely been driven by young people and pushed forward by the isolation of the coronavirus pandemic. In a recent study published by Artsy, the leading online platform for art purchases, 83 percent of survey respondents had purchased art online, up from 64 percent in 2019. Online art market participation was even higher at 91 percent among “Next-Gen Collectors,” a subset of buyers who started collecting in the past four years.

Contemporary trends and exciting innovations suggest a more accessible, democratic future where collecting can be a force for change.

3. A New Transparency in the Market

Even if aspiring collectors have been exposed to craft and have defined their aesthetic preferences, they don’t necessarily know the idiosyncrasies of the craft market. Conservation, documentation, insurance, and deaccessioning are among the many facets of collecting. Some collectors don’t know about the buyer’s premium of auction houses, payment plans, selective gallery sales, or even where to ask questions about these things.

Galleries, museum associations, and other organizations, such as the James Renwick Alliance for Craft (JRACraft), Wood Art Alliance, or Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass, have long brought craft collectors together. They provide rich opportunities for collectors to discover new artists, discuss the field, and learn about the care, management, process, and placement of collections. They also offer programs about documentation, appraisals, insurance, and deaccessioning.

New online resources provide further opportunities to learn about the collecting journey and make the process of collecting far more transparent. Author and art-market expert Magnus Resch concluded from his research that a fundamental issue limiting the growth of new collectors is these artificial boundaries and a lack of information about buying artwork. To remedy this situation, he founded Larry’s List, an online resource and educational outlet for collectors. Artsy also makes the process of collecting more transparent and simplifies the purchasing process. Pricing is clear and artists are easy to find. Artsy publishes statistics about sales and dedicates immense resources to a blog that shares personal stories and scholarly articles about trends affecting the art market.

For emerging collectors who are new to the field, there are exciting new grassroots ways to approach collecting. One is the subscription model. Before the pandemic, the Station North Arts District in Baltimore, for example, offered subscribers quarterly lectures by local artists and then invited them to select their top three artists from whom to receive artwork. Similarly, artwork rental companies, which have mostly served large corporate clients for decades, have been moving online and offering their services to individuals. For those who prefer a modern take on the traditional patron approach, there is Patreon, a subscription service that allows supporters to contribute monthly to someone’s artistic practice. Depending on the artist, a contributor may receive a work in return, early access to exhibitions, and/or regular updates on the artist’s activities.

A new generation of collectors has emerged, and their interests are as diverse as the collectors themselves.

Marilyn Johnson led the initiative to purchase Sonya Clark’s Madam C.J. Walker (2008, combs, 122 x 87 in.) for the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin through crowdfunding. Other donors include Beverly Dale; Buckingham Foundation; Jeanne and Michael Klein; Fredericka and David Middleton; H-E-B; Joseph and Tam Hawkins; Carmel and Gregory Fenves; the National Council of Negro Women (Austin Section); the Lone Star (TX) and Town Lake (TX) Chapters of The Links, Incorporated; the National Society of Black Engineers Austin Professionals Chapter; Greater Austin Black Chamber of Commerce; and National Black MBA Association Austin Chapter. Photo courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art.

4. Collecting as Advocacy

Collecting and personal identity have been intertwined for almost as long as collecting has existed. Famous art collectors such as Peggy Guggenheim and J. Paul Getty furthered the notion of collecting as a pastime of the wealthy elite. Yet collecting has also been used as a tool for social change for decades. Prominent Black art collectors William H. Dorsey and Edward M. Thomas were cultural leaders before emancipation in 1863, and collector Wilhelmina Holladay secured a place for women artists when she founded the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, in 1981. Collectors continue to buy work based on their personal values to advance their identity as individuals and invest in causes they care about.

One lauded example of preserving cultural identity and promoting change through collecting is the recently opened Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture in Riverside, California. This self-described “center of Chicano art” opened with a retrospective of glass artists known as the de la Torre Brothers. Both their exhibition and the center’s permanent collection reflect the values of collector Cheech Marin, a first-generation Mexican American collector and one of the world’s foremost collectors of Chicano art.

Innovation in craft collecting comes from reframing, recontextualizing, and asking questions. How can we reconsider the role of the collector? How can we make collecting and deaccessioning more transparent? What if like-minded friends started sharing resources to buy artwork to support causes they care about? There’s room for more innovation in collecting, and it’s going to take time to overcome the problematic history of the field. These emerging trends offer hope for the future and encourage us to keep asking those vital questions about what collecting means, how it should go forward, and who will participate.

Discover More Thought-Provoking Articles in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.