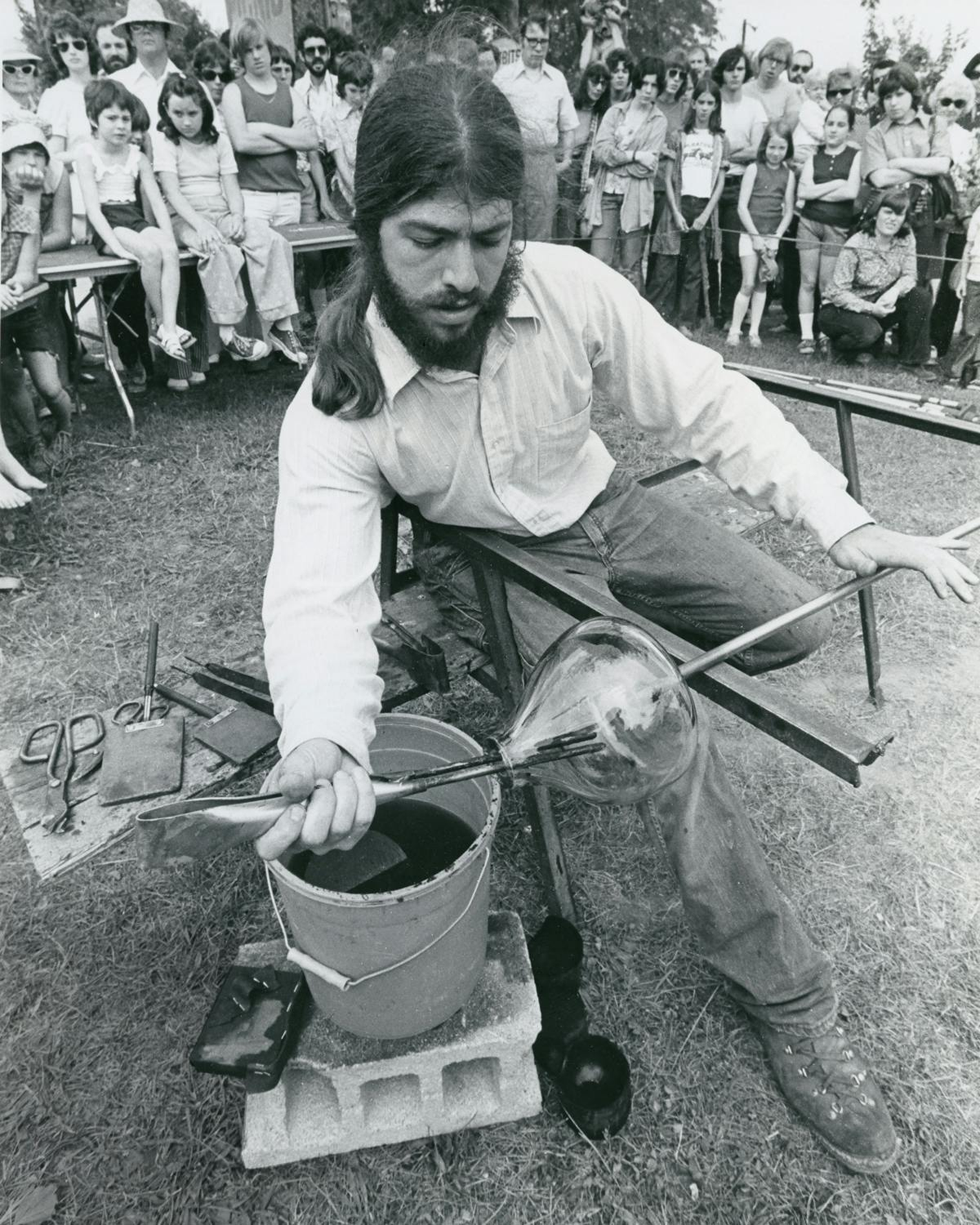

In the 1970s, Josh Simpson set out to make a living blowing glass. He rented a rural property in Vermont, built a small studio and the furnaces he needed, sewed a teepee from sailcloth to live in, and got to work. When he’d crafted several boxes of art glass, he’d pack up his Datsun pickup and traverse the regional highways and byways, looking for shopkeepers to buy his work. “It was tough going,” he recalls. Then Simpson heard about the Northeast Craft Fair 8 in Rhinebeck, New York.

When Simpson arrived, he was astounded. The fair was packed not only with collectors, gallery owners, retailers, and museum curators, but also with people curious about craft. “To meet and talk with a craftsperson, and understand why and how they’re making the work, and to get excited by the artist’s vibe, was so thrilling for people,” he recalls. “Delightful interactions happened.”

Those interactions were also fruitful for the artists. At his first show, Simpson sold all of the glass he’d packed into his pickup, took orders for more, and earned enough money to secure a bank loan for a new studio on his grandfather’s land in Connecticut. Simpson participated in every Rhinebeck fair thereafter, until 1983, and then at other locations for decades. He also built a trailer from which he’d give glassblowing demonstrations during the fairs.

The Rhinebeck fair wasn’t actually the beginning of what would become a phenomenon. Since the 1930s, a movement had been afoot in the United States to develop markets in metropolitan areas for rural craftspeople. In 1940 Aileen Osborn Webb formed the Handcraft Cooperative League of America in Vermont, and her friend Anne Morgan started the American Handcraft Council in Delaware. In the same year, America House, a retail outlet operated by the League, opened in New York City. Two years later, Webb and Morgan’s organizations merged and became the American Craftsmen’s Cooperative Council (ACCC)—the precursor to today’s American Craft Council (ACC).

Glass artist Josh Simpson demonstrates glassmaking techniques at the 1974 ACC Northeast Craft Fair held in Rhinebeck, New York.