Emerging Voices: Announcing the 2019 Awards

Emerging Voices: Announcing the 2019 Awards

The American Craft Council’s biennial Emerging Voices Awards honor the talents of remarkable young makers and thought leaders who are shaping the future of craft. You’ll meet this year’s seven honorees, each of whom is within five years of significant training.

“ACC is committed to supporting new, diverse voices and material practices shaping the field of contemporary craft,” says ACC executive director Sarah Schultz. “We’re excited to see how this cohort of artists will continue to break new ground.”

Many thanks to our 2019 Emerging Voices jurors: Beth McLaughlin, chief curator of exhibitions and collections at Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, Massachusetts; ceramist Jennifer Ling Datchuk, the 2017 ACC Emerging Artist; and textile artist Michael Radyk, a former director of education for the ACC.

Emerging Artist: Diedrick Brackens, Los Angeles

Since early on in his textile studies, Diedrick Brackens has been drawn to silhouettes for what he calls “the psychological effect they have on a viewer.” He cites several Black artists who have used them in their work – Bill Traylor, Aaron Douglas, Kerry James Marshall, Belkis Ayón, and Kara Walker among them – as influences. Woven with cotton that he hand-colors with everything from commercial dyes to tea to bleach, Brackens’ tapestries are not only a nod to the legacy of Black fine artists in the US and abroad, but also to the textile artisans of Western Africa, the American South, and Europe whose work has often been dismissed as inferior for its ties to domesticity.

The past couple of years have been busy ones for Brackens. In 2018, he was awarded the Studio Museum in Harlem’s coveted Wein Prize, and his work was featured in the “Made in LA 2018” biennial exhibition at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Most recently, he had a solo exhibition at the New Museum in New York that closed in September.

Through his tapestries, the 30-year-old explores life as a Black queer man in America by threading together personal and historical narratives. Some tapestries are composed of abstract images. Others, which draw on actual people and events, depict backlit figures in a landscape. All pose pressing moral, spiritual, and political questions through an eloquent symbolism, layered with material and conceptual references that he builds like a collage.

By working with cotton, a fiber with inextricable ties to the enslavement of Black bodies in US history, as his primary material, Brackens pays tribute to those who came before him. The opportunity to do so under dramatically different circumstances from his forebears makes the weaving process both an act of contemplation and of activism.

Through his work, Brackens also seeks to raise poignant questions about gender: What does it mean to be a man practicing the art of weaving, which historically has been viewed as “women’s work”? How do perceptions about textile art shift when it is practiced by a man? Furthermore, how can rendering powerful narratives about history, injustice, and identity in fiber art make them more meaningful? Brackens’ vivid, lyrical tapestries present us with thoughtfully layered and complex allegories through which to consider those questions.

What do you know now that you didn’t when you started?

I was first attracted to weaving, like so many others, because of its meditative quality and the way that structure and order are built into the process. But very quickly these things began to feel limiting, like restrictions. Now, with over 10 years of experience, I find that weaving is quite malleable. It used to feel like math or an equation, very finite. Now it feels expansive, like drawing or writing.

What is your favorite part of the process?

Dyeing the yarns and weaving. These are parts when I must engage my mind, my eyes, and every limb in order to achieve the desired colors and forms.

What is an ongoing challenge?

Time.

What are your hopes for the larger craft field?

That we continue to expand our definition of what constitutes craft and continue to find ways to bring more diverse makers into the field. One of the biggest barriers to participation is expense, from the cost of specialized tools and materials to instruction. I also believe the ways we have professionalized the field need to be rethought in order to encourage participation and make room for new voices.

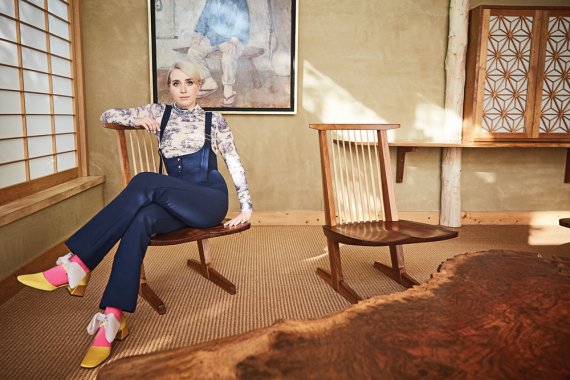

Emerging Scholar: Sarah Darro, Philadelphia

Writer and curator Sarah Darro sees craft as much more than a mode of artistic production. For her, it’s also a form of discourse, and one that’s increasingly helpful in studying American culture today. “The way it is entangled with every type of cultural production, yet is removed enough from stratified disciplines and industries to maintain a critical distance, allows craft to be a lens rather than a bounded category,” she says. It’s that flexibility that makes craft “uniquely positioned to host critical conversations.”

Darro, 29, first studied anthropology and art history at Barnard College of Columbia University in New York before earning her master’s degree in visual, material, and museum anthropology from Oxford University in 2014. But it wasn’t until she was awarded a three-year Windgate Foundation curatorial fellowship at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft four years ago that she says her practice came into focus. Before then, “my research was primarily concerned with investigating the power structures of the built world and understanding objects as actors in our social fabric,” she says. That makes the field of contemporary craft and design a good fit for her interests. “It’s built upon a history of makers who understood the power of objects and materials to catalyze culture.”

Now Darro is working collaboratively with artists to re-envision the ways we speak about, write about, exhibit, and experience craft.

What do you address in your work?

I want to address contemporary culture – its identity politics, its museums, its architecture, its legal systems – all through the lens of craft. Craft is a field founded on the transformation of material through specialized skill, process, and embodied histories. My curatorial ideology is founded on the transformative potential of the art-viewing experience. I strive to build exhibitions that allow for authentic engagement with the objects and critical concepts being put forth by artists.

By applying the nimbleness of the exhibiting artists in navigating material and process, and by problem-solving across disciplines to build exhibitions with them, I strive for a curatorial practice that reaches diverse audiences and responds and adapts to rapidly changing cultural priorities and problems.

What do you love about conducting research and writing?

The thrill of following a lead and pulling threads that seem tangential or unrelated but ultimately work in concert with larger themes, ones that may become significant years down the line or manifest in a different project. I am also invigorated by the ways in which research and fieldwork generate community.

Research has been the connective tissue for me to access a dynamic orbit of archivists, librarians, oral historians, scholars, and artists in the field. It is my instrument for tapping into specialized knowledge and institutional support.

More than any other act, writing incites conceptual discovery for me. It is where the big picture ferments. I often find my thesis emerges or changes during the writing process. I’ve also found that co-writing and co-interpreting is incredibly valuable in elevating curatorial practice and discourse.

What makes a great exhibition?

A great exhibition feels much like an essay’s argument, but in physical form. As you move through a show, the artworks, the relationships established through their placement, and the accompanying writing and educational materials act as evidentiary support.

What is an ongoing challenge for you?

I struggle to reconcile curating – which, historically, is hegemonic in perspective and approach – with an increasingly complex and intersectional contemporary moment, one that necessitates redistributed and shared authority. This is a challenge for curators and museums in general. How can we subvert traditional models and instead curate collaboratively, equitably, and with a decentralized approach? I am working to develop strategies for decentralizing my own curatorial practice by collaboratively establishing curatorial frameworks and advisory panels from the outset, with voices from inside and outside of the field.

Shortlist Artist: Marisa Finos; Pawtucket, Rhode Island

In her ceramic art, Marisa Finos engages with the complexities of death and dying as a way of probing the deep disconnection between US society and those topics. Through clay vessels, sculptures, and performances, she brings the inescapable experience of death up close and personal, to challenge the distance and denial we’ve cultivated.

“In generations past, death was a larger part of life, and people were involved through each step of the process,” she says. “Now, death happens at a far distance. As a result, we struggle to connect with mortality, death, and grief because we don’t know how to allow the space for it.”

In her work, the 33-year-old artist expresses the natural stages of life that clay and the human body share. “Like clay, we are malleable beings, constantly molding into different forms as our bodies record each touch, experience, and exchange,” Finos says.

The many life stages and transitions we undergo also share striking similarities with clay. “Eventually, clay dries and becomes fragile, and has the ability to either be reclaimed and reused for future purposes, or fired to withstand time,” she says. “I like to think that, upon death, our bodies have similar options.”

What do you know now that you didn’t when you started?

At the time I began my Vessel series, I didn’t realize how many obstacles I would encounter nor what it would take in order to maintain my practice. I didn’t have a studio or access to ceramics facilities then, so I had to change my way of thinking and making. I relied on various residencies and exhibitions to make this body of work.

What is your favorite part of the process?

The most exciting parts for me are when I’m sitting or standing in the middle of the piece and coil-building around my body. Watching the vessel slowly grow around me puts me in a meditative state.

I also enjoy the very end stages of building, when I slowly begin to enclose myself inside. It’s just me. I’m all alone and completely present with myself. I sit inside the hollow form, feel the cold dampness of the clay, observe the marks left by my hands, and start to understand how I connect to the vessel. The unknown parts of the process – the things I can’t anticipate or plan for – at the end bring me the most satisfaction. I’m always left with a positive revelation, a new discovery or an observation about the work or myself.

What inspires you?

I want to make vessels of different forms and scales to experiment with how sound travels through them. I’m interested in using one’s own voice to explore the vessel as an instrument, communication tool, or container of sound. Inside the vessel, a person is surrounded by their own sounds and voice. I’m interested in collaborating with vocalists, musicians, and performers to further explore these qualities and potentials.

What is an ongoing challenge?

The creative cycle ebbs and flows over time, and that’s a huge lesson I’m trying to learn. If I’m not making at this moment, it doesn’t mean I’m any less of an artist.

On a continuum of inward reflection to outward expression, where do you and your work fall?

I would say I fall right in the middle, quite literally and figuratively. I create to understand myself and how I exist within the world now, and beyond death. I’m often motivated by my frustrations of not feeling allowed to discuss the complexities of mortality and death, so I create my own conversation and invite others to join me.

Shortlist Artist: Luci Jockel, Philadelphia

Luci Jockel is intrigued by the fragility of ecosystems and the many nonhuman lifeforms within them, which she memorializes in her jewelry. By crafting intimate, wearable opportunities for people to experience reverence for these overlooked-yet-vital organisms – from honeybees to lichens to muskrats – Jockel says she helps people understand “the harm humans have been inflicting on our environment and onto these fragile and beautiful living organisms.”

Her artistic mission is shaped by the wooded environment of her childhood home in Western Pennsylvania. “I was surrounded by a diversity of ecosystems,” says the 28-year-old artist. “I was always attracted to what was overlooked and began collecting things I could fit into my pocket. I knew I wanted to somehow show others, to see – to really see – these treasures.” Jewelry, with its inherently precious and emotional qualities, has given her the means to do so.

How has research influenced your practice?

Jewelry has a rich history of sentimentality and memorialization. While I was a graduate student at Rhode Island School of Design, I studied the mourning rituals of many cultures. I learned that mourning practices vary, but they have one thing in common: memorializing loved ones using their physical remains, from hair clippings in Victorian mourning jewelry to the full skeletons of Roman catacombs drenched in jewels. In these cultures, the remains acted as a bridge between the realms of life and death, and assisted in the grieving process.

What do you know now that you didn’t when you started?

Working within a community is so important for my practice. I used to dream of an “ideal artist’s life” of seclusion, making work day in and day out. While this may work for some, my practice would be stagnant without community and others to bounce ideas off, and to gain momentum and learn from.

What is your favorite part of the process?

Getting lost in an idea for a new piece. This is the moment when everything else fades away and is one of the reasons I keep doing what I do. That part of the process is where the passion is for me.

What inspires you?

My work emerges from my own personal experiences with my surroundings and the relationship I have or seek to have with them. For example, my 2018 series Linked is based on my upbringing in Western Pennsylvania, where hunting is a cherished tradition. Being brought up to normalize the killing of animals, while simultaneously being surrounded by a diversity of fauna and flora that enriched my childhood, has definitely affected my views of our relationship with the environment and caused me to question what I saw as a contradiction of loving yet killing.

The work begins from this introspective place, but it is my hope that the work functions as an emotive device that generates discussion of environmental issues on topics such as ecological imbalance, colony collapse disorder, mass extinction, and climate change.

What is an ongoing challenge?

It is easy to become comfortable with one’s work and to keep producing what feels familiar. It can be a challenge to explore other avenues, but there is no learning if you are not pushing boundaries. I strive to always be in a place of not-knowing.

What are your hopes for the larger craft field?

It is my hope that it makes more of an effort to be more inclusive of a wider range of voices. I also hope that the craft field continues to be critical of general historical practices, ideas, and techniques. As a craftsperson, it is important to master a skillset and to understand the history of one’s medium, yet I believe that in order for craft to be relevant and to enter new territory, it is imperative not to be hindered by what is historically considered “right” and rather rebel against established rules. Breaking that barrier is necessary if we want the field to reach new limits.

Shortlist Artist: Raven Halfmoon; Helena, Montana

Raven Halfmoon (Caddo Nation of Oklahoma) has always been an artist. She doesn’t remember a time when she wasn’t drawing and painting. As a child, she explored many forms of making, including building traditional pottery with her elders, but it wasn’t until she was a sophomore in college that she fell in love with clay. Ever since, she’s been honoring the storied history of the medium within her culture.

“Ceramics is something that dates back thousands of years within my tribe,” says Halfmoon, 28. “It is an art and tradition that has been revered not only in Caddo culture, but across Indigenous societies since time immemorial. These crafts are part of the foundation of our tribal heritage. They tell our story and are passed from generation to generation.”

What does your work explore?

My art is an extension of me, as I continuously try to understand my place within the world, within my tribe, within society, and within the fine art world. It is important for me to emphasize that Caddo people and American Indian people are relevant and continue to build traditions and create with clay today. My artwork exists to break the mold of the Native American stereotype and to simply say, “We are still here, we are resilient, we are powerful, and we are important.”

What have you not yet addressed in your work but want to?

I would like to start incorporating comedy into my work. The subject matter and issues I talk about can be hard and heavy hitting. I would like to start making a body of work that incorporates humor, even if dealing with serious content.

What is your favorite part of working with clay?

Getting my hands dirty. I enjoy every part of the building process, from coil-rolling to shaping details of a face. When I create a piece, I am very precise about what the outcome should look like and, for me, I enjoy the challenge of re-creating my idea or sketch. I also love glazing. In the past, I have painted on 5-foot canvases, so glazing my large heads or figurative sculptures satisfies me in a similar way.

What is an ongoing challenge for you?

I am constantly challenged by the technicalities of building large-scale ceramic artwork. The real challenge for me is not coming up with concepts or ideas, but physically executing the sculptures. Half of the challenge is not even the building of the sculpture itself, but figuring out how to move, fire, unload, ship, and store it. However, I believe being challenged is instrumental to producing great work. It’s what keeps me in the craft field.

What is something you’ve been surprised to learn?

How small the art world is! Use your connections and network at exhibitions, shows, and conferences. It has helped me tremendously.

What are your hopes for the larger craft field?

Craft acts as a carrier and a physical manifestation of culture. I view the field of craft as a direct line and connection to our past, our history, and our ancestors. We have the same materials and tools – our hands – as those who came before us, and we carry the mantle forward for the next set of makers.

Craft and, specifically for me, clay carry a rich story and history. Clay, for example, has been a material used for thousands of years by American Indian tribes throughout the nation. Each tribe used clay in their own specific way to make functional objects, ritualistic pieces, etc. How each piece was made and decorated can be traced back to a specific region and point in time for that tribe. Clay as a material alone carries such a unique and intricate history, which is why I am drawn to ceramics.

Shortlist Artist: Bukola Koiki; Richmond, Virginia

As a child in Lagos, Nigeria, Bukola Koiki was fascinated by her maternal grandmother’s upright loom, her mother’s style, and her Yoruba culture’s long history of cloth weaving, dyeing, textile decoration, and basketry. When she moved to Texas to study communication design in college, however, that interest was suppressed in an attempt to assimilate into American culture, she says. But after returning to Nigeria for an extended visit, she was reminded of all the pleasures of craft and went on to receive her MFA in applied craft and design from a joint program between the Pacific Northwest College of Art and the now-defunct Oregon College of Art and Craft.

It was there that Koiki, 41, began developing her practice of combining textile art with intensive research to explore issues of memory, dislocation, and cultural hybridity. “The work I make always starts from a nagging question about the world, which causes me to reflect on my own views, personal experience, and insights about a pressing topic,” she says. “I’m a maker whose work holds a mirror up to the world and hopes it looks back, finds something familiar, and starts a conversation.”

What are you working on now?

I started a series of large embroidered collagraphs (prints made from low-relief materials affixed to a background), and it has been challenging to stitch through two layers of white netting because it has an almost hallucinatory effect. As part of this work, I’m also attempting to print with palm oil. Figuring out how to do it practically has been frustrating, yet exciting, because it’s new and unusual. It is my hope that my work always surprises me. When it ceases to do so, then it’s time to move on to other pursuits in life.

What have you not yet addressed in your work but want to?

I have an ongoing fascination with understanding my place in Nigerian history as a child born in post-colonial Nigeria in which the presence of British colonizers is still felt, in ways big and small. Using a recently discovered colonial-era government text as a Rosetta Stone of sorts, I seek to understand the factors that led to Nigeria becoming a colonized country: the history, complexities, and complicities of the people, corporations, and entities involved in the trade of slaves, crops, and other valuable natural resources to Europe and the Americas. I am mining this book, as well as embarking on other personal, visual, and textual research, in the seemingly elusive hope of knowing my ancestors. By learning from them and through them, I hope to begin to know myself, my family, my country, and how the events of the past have shaped this divisive and uncertain present and future we find ourselves in.

What do you know now that you didn’t when you started?

I didn’t know how many of my feelings and ideas about fiber were influenced by Western culture. Ironically, it was taking a craft history class in grad school that opened my eyes. I was appalled at how Indigenous knowledge, history, and cultural beliefs were whitewashed or omitted altogether. Realizing how few of the movements, constructs, and canonical artists resonated with me, or made me feel included, inspired me to dig deeper into the craft histories of Nigeria and West Africa.

What are your hopes for the larger craft field?

One of my hopes is tied to my challenges: that the larger craft field fully embraces intersectionality and that artists of color and their work are not merely tokenized.

I would also like to see where the ongoing conflations of digital technology and craft propel the field in the next decade and beyond. I think experimental techniques like 3D-printed textiles and ceramics and the like make a lot of tradition-bent craftspeople bemoan the loss of “the hand” in craft, but the craft world (like every industry) must innovate. That is why craft schools matter and why the many recent school closings are worrisome, because only by knowing our history and how far we have come can we ensure that the future of craft never loses sight of the humanity that seeded it into the universe.

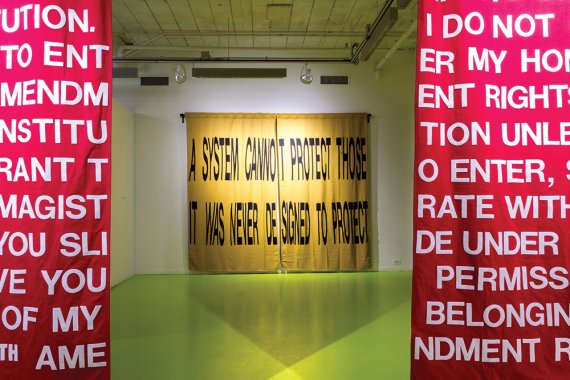

Shortlist Artist: Aram Han Sifuentes, Chicago

Aram Han Sifuentes merges handwork, performance, and education in her socially engaged projects to get people talking about immigration and the myriad related, often unacknowledged, issues that exploited people living and working in the margins of society face. Using fiber as her primary material, the 33-year-old artist aims to create empowering spaces for individual and collective changemaking.

Projects such as the Protest Banner Lending Library, both a place where one can check out banners and a series of workshops on making them, aim to build community and provide a productive outlet for those who want to take political action. Other projects focus on education. The ongoing US Citizenship Test Sampler, which welcomes non-citizens to stitch questions and answers from the test onto fabric panels, provides a way for participants to study for it in addition to illustrating for the public the obstacles of obtaining US citizenship in a tactile way.

For Sifuentes, the work is personal. When she was 5 years old, her own family emigrated from South Korea to California, where she experienced firsthand the financial challenge of settling into a new country. Finding employment was not easy for her family, and her mother, a seamstress, taught Sifuentes to sew when she was 6 so that she could spend time with her daughter while she worked.

Now Sifuentes draws deeply on her family’s history in her practice. “My family’s immigration experience is not uncommon – how we struggle, how we survive and thrive, what type of work we find ourselves doing, what types of discrimination and racism we face on a daily basis, and what sacrifices we make for the next generation,” she says.

What was your first community sewing project?

I started that with my ongoing project US Citizenship Test Sampler, where I invite non-citizens to stitch the citizenship test questions on samplers. Each participant picks a test question and answer to complete, and it becomes a way to study for the test. Each of these samplers are for sale for $725, the cost of applying for citizenship. The money goes to the maker.

You often use written language in your work. Why is that important to you?

Words frame the way you see the world. Words also reveal a lot about their users, in terms of perspective, philosophy, and attitudes. I read a lot and find so much power and strength from the books I read, so I have always found a lot of power in words.

I do think written language has become a bigger part of my work in recent years, when making simple declarative statements for the protection of people of color and immigrants has become necessary.

Why are sewing and embroidery meaningful to you?

They are forms of literacy and language in and of themselves. I also cannot see sewing devoid of the exploitative labor practices of textile factories throughout the world. How can the language of embroidery and sewing flourish when it is more and more controlled by the manufacturing industry and when the conditions for creativity become economically unsustainable?

How is your practice growing?

I’ve been doing much more writing of short stories, poetry, and experimental texts. Much of these texts come from my personal stories of family, ancestry, PTSD, healing, and teaching.

What’s something you learned since you started making art?

To speak your truths without hesitation. If you feel it, it is because it is so, and you are not alone. It is imperative to talk back to power.

What is your favorite part of your practice?

Meeting people all over the world who use art and music to create change.

What is an ongoing challenge?

That the works of people of color are merely seen as representations of our people. When will dominant culture step aside and resist the urge to define us?

What are your hopes for the larger craft field?

I want the field to dismantle the power structures it is built upon that keep people of color out.