The Connector

The Connector

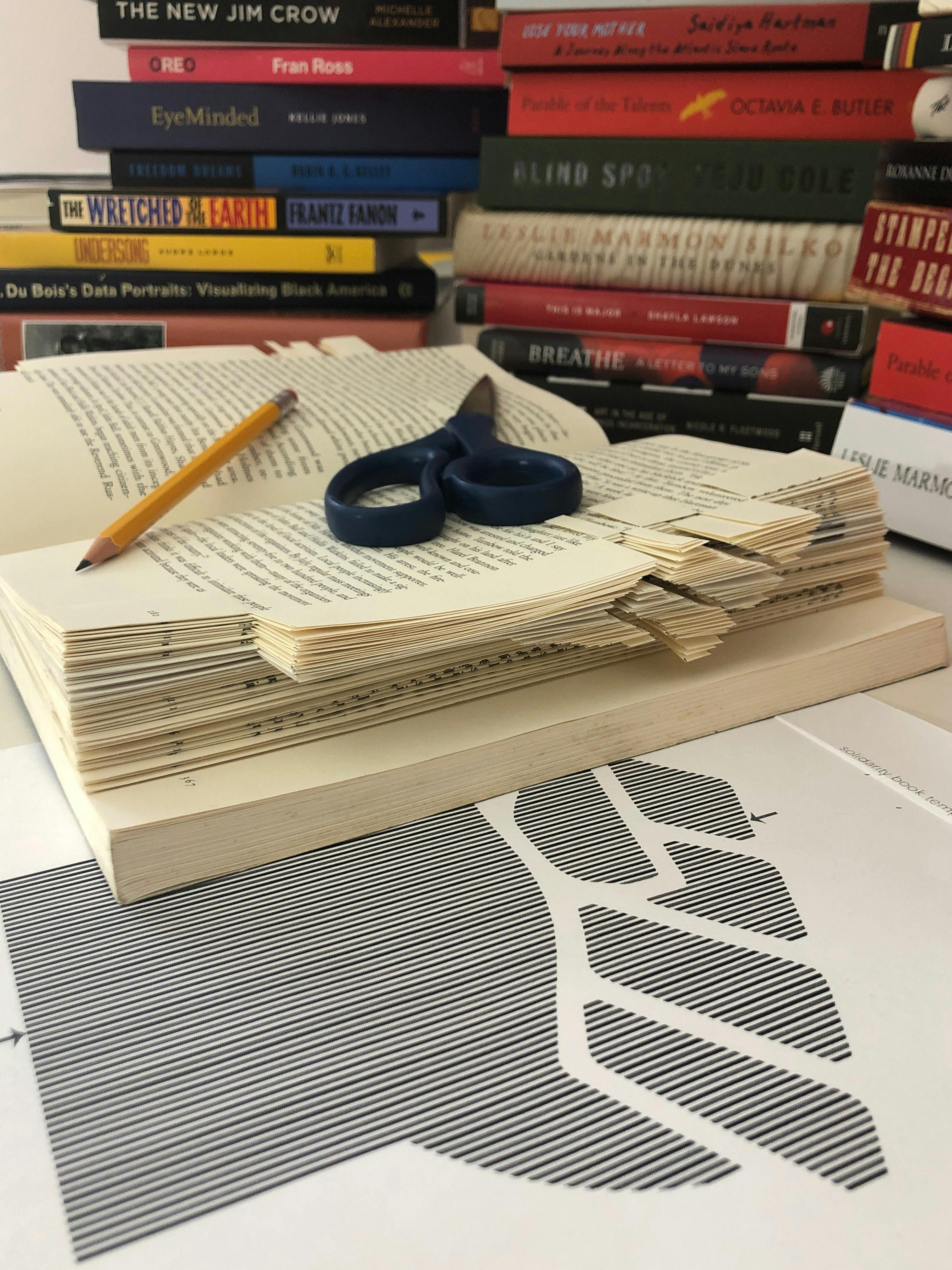

Many participants reshaped books for Sonya Clark’s Solidarity Book Project, here exhibited at Amherst College. Photo by Maria Stenzel, © Amherst College.

Anyone could join in. The prompt was simple: take a book that has taught you about solidarity with Black and Indigenous communities and carve a solidarity fist into it. During the initial year of the project, Clark asked participants to mail the books to her. They were exhibited as part of Amherst College’s 200th anniversary in the fall of 2021, which was also the 50th anniversary of the Black Studies Department and the fifth anniversary of student activism that had resulted in the hiring of more faculty of color (including Clark).

As part of the project, Clark partnered with Amherst—named after Jeffery Amherst, who advocated for the use of biological warfare against Indigenous peoples—to financially match participation in the project. For every individual who read an excerpt or sent a book, Amherst contributed up to $200 to be donated to organizations supporting Black and/or Indigenous communities. The project raised $100,000.

Clark holding a book cut and folded into a solidarity fist. Photo courtesy of the Solidarity Book Project.

In response to people who want to donate money directly to the project, Clark says, “I don’t want your money. I want your participation in this visual and communal work of solidarity.” In December 2021, the website that serves as the project’s digital archive was launched, where a virtual monument is being constructed out of photos of sculpted books. People are encouraged not only to sculpt their own books but also to launch their own projects—to build community, create public monuments, and partner with institutions that have benefited from colonialism, in order to give back to Black and Indigenous communities.

Each cut and folded book in the Solidarity Book Project, 2021, taught someone about solidarity with Black and Indigenous communities. Photo courtesy of the Solidarity Book Project.

The Solidarity Book Project asks us to think about the work of solidarity and, through art, to practice what liberation looks and feels like through our collective making practices. It allows us to see the true power of our actions through how they wondrously ripple, combine, and build off the work of others.

This collaborative approach, giving voice to the power of the collective, is fundamental to Clark’s work as an artist. “I can unpack anything as a collaboration,” Clark says. “When I draw with a pencil on a piece of paper, I didn’t make the pencil, I didn’t make the paper, I didn’t even make this hand. Genetically there are more people in this hand than I can count. There are multiple people in the room already, and all I’m doing is drawing. We’re never singular. We’re always in community. Even though one body might be in this space, that body is also this composite of many.”

Polyvalent Artist, Powerful Vision

Born in Washington, DC, and raised by a Trinidadian psychologist and a Jamaican nurse, Clark rose to international fame with powerful and intricate artworks using hair and flags to express complex aspects of African American identity, pride, and struggle. Collaboration is present in nearly all of them.

In Hairbow for Sounding the Ancestors (2013), for example, she rehaired a violin bow with a dreadlock of her own hair and asked jazz violinist Regina Carter to use the bow to play “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (aka the Black national anthem), “America the Beautiful,” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” in a public performance.

For Skein (2016), expert hair braider Kamala Bhagat gave Clark all the dreadlocks from the head of one of her customers; Clark connected them into one very long dread representing the approximately 80,000 individual hairs on a typical human head. The point, and the heartbreak, of the piece is that 80,000 is also the number of Africans enslaved by Europeans and transported in a single year at the height of the slave trade.

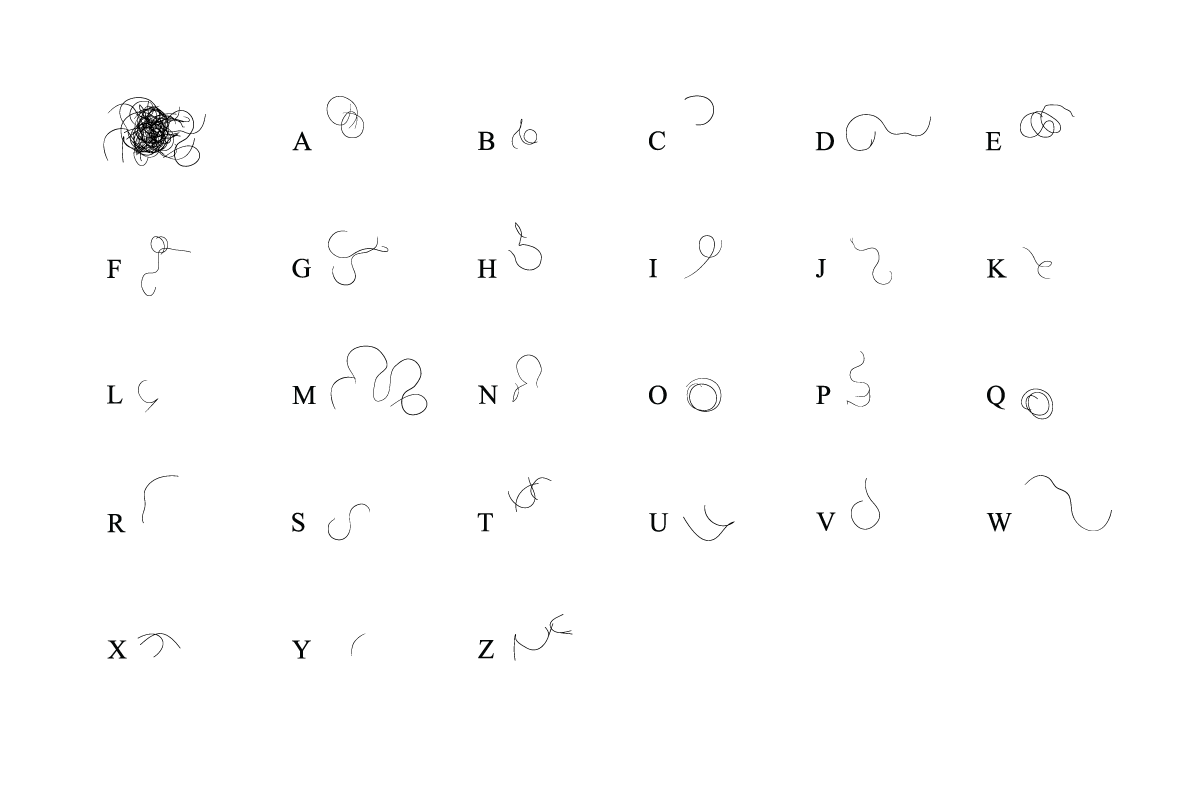

Six years ago, in collaboration with graphic designer Bo Peng, she developed a digital type font by snipping off a lock of her own hair and instructing Peng to pull all of the letters from the shapes present in her own curls. It’s a personal gesture, of course, but also a critique of how the Roman alphabet has come to dominate so much of how we communicate with each other and document reality; the font is also a way of acknowledging the many African languages still colonized by the script of the Roman Empire. Although Twist (the typeface was named by poet Rita Dove) is based on the 26 letters in the Roman alphabet, this unique script has quite literally grown out of the head of a Black woman artist.

“I can unpack anything as a collaboration.”

—Sonya Clark

TOP: Skein, 2016, is made from dreadlocks. Photo by Taylor Dabney. BOTTOM: With graphic designer Bo Peng, Clark developed the typeface Twist, 2016, using her own hair. Photo courtesy of Sonya Clark.

“I am hard-pressed to point to a Black woman who is an artist who has not made work about hair or at least contemplated it,” Clark says. “I’m someone who thinks about hair as a medium, as an art form, and as the carrier of our DNA and our heritage and our ancestors, something that actually outlives us. The rest of my body could go to dust, but my hair will exist and persist. It becomes a lineage; it remains.”

Trained as a textile artist, Clark says she will always be able to make artwork around hair, which of course is a fiber. She points out that although weaving has historically been seen as mere “women’s work” or the production of a taken-for-granted commodity by low-skill labor, “we wouldn’t even have the technology that we’re so dependent on right now if it weren’t for the complexity of a loom, that early jacquard loom that had the punch-card system that led to the punch-card system of early computers, and then to today’s tech. I often say to people, You wouldn’t have a microcomputer in your pocket if it weren’t for a loom.”

Then there are the flags. In Unraveling, a series of performances beginning in 2015, Clark has invited audience members to join her in unraveling a Confederate flag. Her traveling exhibit Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know, launched in 2019 at The Fabric Workshop and Museum, reframed and highlighted the little-known Confederate Flag of Truce, a repurposed dishcloth that ended the Civil War at Appomattox. In a related performance, Reversals, Clark used a dishcloth printed with a Confederate flag to clean a floor covered in dust gathered from Independence Hall and Declaration House, to reveal the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence. “Maybe you can use the master’s tools to undo the master’s house, right? Sometimes,” she says.

Clark works with gallery and museum audiences to take apart Confederate battle flags for Unraveling, 2015–present, a performance piece. Photo by Taylor Dabney.

Constantly making more connections, Clark has built a career that encompasses far more than the two signifiers—hair and the flag—most closely associated with her. The full range of her work is vast and multifaceted, incorporating not only other people and books, but also beads, cloth, combs, copper, and sugar, and practices like weaving, sculpture, and performance. Her vision operates on many scales and many registers at once: from the earth and its processes and the chemical bases of life to the realm of history and the historical struggles of people of color—and on into the stars.

Beads and Star Seeds

One long-term collaboration that shows Clark’s love for the grand scale, her sense of language and history, and her tendency to reach for the transcendent while remaining tethered to the earth is The Beaded Prayers Project, which Clark started in 1998. In it, she asks people of all ages and backgrounds to create beaded packets that contain their prayers, wishes, hopes, or dreams. “I’m not a religious person,” she says, “but I love the idea that bead, in this language that I’m speaking to you in, is synonymous with the word prayer, because beads were used as a mnemonic device to understand where you were in your rosary bead cycle.”

The work has involved more than 5,000 people in dozens of countries, and it’s the oldest and longest project she has done. “Five thousand physical people couldn’t fit in a room, but their presence can,” she says. “And the rooms do feel powerful. Whenever I’m with The Beaded Prayers Project, I’m like, ‘Still feeling it? I should be used to it by now!’ But the power is still there.” So powerful that in 2021 the city of Detroit asked her to create a version called The Healing Memorial to address the losses of that community during the pandemic. Already the participants in that version number in the thousands.

“Five thousand physical people couldn’t fit in a room, but their presence can.”

—Sonya Clark

TOP: At The Gallery at VCUarts Qatar, visitors experience The Beaded Prayers Project, 1998–present. Photo courtesy of VCUarts Qatar. BOTTOM: A closeup of beaded packets that project participants made to hold their prayers, wishes, hopes, or dreams. Shown here at The Textile Museum in Washington, DC. Photo courtesy of Sonya Clark.

Clark has connected the Black centuries-long struggle for liberation with cosmic and transcendent powers and values. Finding Freedom (2020) is a case in point. Commissioned by Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a stop on the Underground Railroad, it’s a 1,500-square-foot quilt—the largest piece she’s ever created. She asked individuals from many places, including the Czech Republic, a prison in Massachusetts, and an artists’ retreat in Maine, to sprinkle vegetal seeds “randomly and quickly” on the textile squares, each treated to create a cyanotype. This photographic process produces cyan blue images on the parts of a treated surface exposed to the sun. The places the seeds landed remain dots of white that look like stars. The point was to create a sort of cosmos of freedom.

“Harriet Tubman and other freedom fighters and abolitionists were also astronomers,” Clark says, “because they were looking to the sky to understand where we are on this earth but also looking to the sky to access their freedom. Which is just like this beautiful thing, like you’re here, planted on this earth, and you’re looking to distant suns to understand how you can navigate your way toward the freedom that is rightly yours, but someone else has made you unfree.”

Clark wants viewers to consider the present, and “the many freedoms that are taken away all of the time.”

TOP: A closeup showing the white star pattern left behind on this cyanotype by scattered seeds blocking exposure to the sun. Photo courtesy of Sonya Clark. BOTTOM: At the Phillips Museum of Art in Lancaster, Pennsylvania—a site along the Underground Railroad—viewers of Finding Freedom, 2020, use black light flashlights to look for one of the Big Dippers in the quilt. The constellation points to the North Star, a guide for enslaved people fleeing to the North. Photo courtesy of Phillips Museum of Art at Franklin & Marshall College.

Clark chose seeds of plants that serve as food for humans to call attention to precisely who was, and is, working the land—enslaved people, migrant workers, and individuals “enslaved in the carceral system,” to use her words. A suggestion from one of the men at the prison in Massachusetts eventually led to illuminating Finding Freedom with black lights, making the white and blue contrast even more vibrant. The result was a visually stunning patchwork canopy that hung from the ceiling at the Phillips Museum of Art at Franklin & Marshall and more recently at the Jepson Center of Telfair Museums in Savannah, Georgia, the various shades of blue speckled with glowing constellations of white dots.

Embedded within the canopy of random stars are several intentional Big Dipper constellations. Each one points to a North Star, the star enslaved people followed as they fled north. Viewers of the quilt, carrying black light flashlights, can gaze up into those stars. “You see the problem there, don’t you?” asks Clark. “You’re in a white gallery space, you’re happy, and Finding Freedom is a piece of wonder. It’s blue—everybody loves blue. . . . Your life isn’t at stake, there are no hound dogs chasing after you, no bounty hunters, none of that. None of the really terrible part of it is in the experience. In no way is this gallery experience even close.”

Instead, she says, she wants viewers to consider the present, and “the many freedoms that are taken away all of the time,” and to reflect on a Toni Morrison quote: “The function of freedom is to free someone else.”

TOP LEFT: Using a photographic process, cotton quilt pieces for Finding Freedom, 2020, were exposed to the sun to create blue images. BOTTOM LEFT: After being exposed to sunlight, the cloth cyanotypes go into water with hydrogen peroxide, which turns them dark blue. TOP RIGHT: A pile of finished pieces created by art school students, people who are incarcerated, and others. BOTTOM RIGHT: Clark and a participant at work on the quilt. All photos courtesy of Sonya Clark.

Clark is also thinking about the many ways the sky has been colonized by Europeans. Many cultures have names for the constellations though we commonly use those designated by Ptolemy. She asks us to consider how the act of looking up into the night sky to the stars is a privilege denied those who are incarcerated or living in dense urban areas. “Who gets to see the night sky?” she asks. “If you’re a kid growing up in the city, and your city is filled with light pollution, you actually don’t know what the Milky Way looks like or even why it’s called that.”

Connecting people and the sky, the loom and the cell phone, books and signs of solidarity. Bringing thousands of people into a gallery in the form of packets full of dreams. Adding a cosmic dimension to freedom struggles and representing that connection by turning tiny seeds into stars. These are powerful examples of how Clark’s mind works: she sees seemingly simple things in the context of great stretches of space and time and is always mindful of how age-old practices like weaving and food growing connect to contemporary issues. Then, with the help of others, she turns all of this into beauty that can open hearts and change minds.

sonyaclark.com | @sysclark | solidaritybookproject.org

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.