The Body Eloquent

The Body Eloquent

For Cristina Córdova, the expressive potential of the human form knows no bounds.

How does an artist take a timeless form and make it her own?

Cristina Córdova, who sculpts the human figure in clay with great skill and sensitivity, knows the allure, and challenge, of working in a format that has captivated artists since time immemorial.

“Because it is such a monolithic tradition that you drag in, it’s hard – especially in the contemporary setting of art – to use the figure in a way that does not drag you back, that is perceived as fresh and valid,” Córdova, 35, observes. Then again, there is no limit to what she describes as “the potential of the eloquence of the body to manifest a state of mind.”

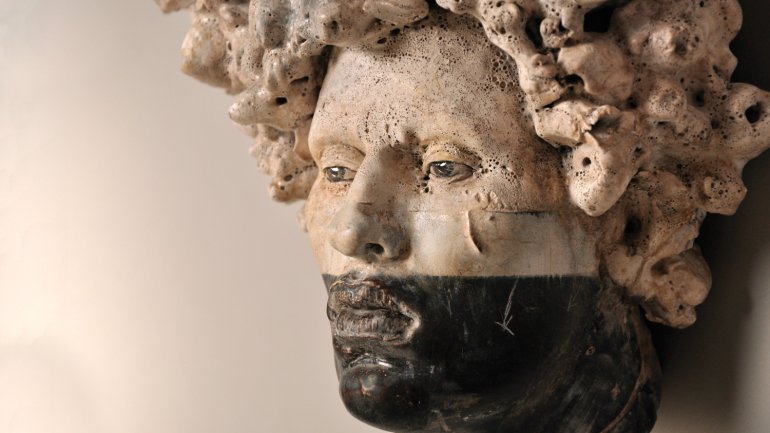

And so Córdova creates players on the stage of life, captured in moments of transition as they reveal themselves through gesture, from wild contortion to the subtlest lift of an eyebrow. Her figures range from tabletop size to larger than life. Some are black, others white (usually a choice made for aesthetic reasons, Córdova says, though she acknowledges color can be a charged element as well). They may be riding a beast, or adrift on a boat, or perched on an island in an archipelago, ready to hop to the next place.

Some read as motionless, yet radiate emotion through their stance, surface texture, and accoutrements, gazing down from high on a wall or pedestal, or reclining in the nude. How will all their dramas play out? That’s largely up to us.

“When you look at ballet, there is a loose narrative, a thread. But it’s not very overt. In modern dance it’s even less so. That’s how I’ve approached these figures. I’m not interested in being terribly clear about the story.”

Córdova was a dancer through her childhood and into her 20s, so it’s no surprise she’s inspired by the body, movement, and theater, nor that she finds her expressive sweet spot in a delicate balance – that of the personal and the universal.

“I feel my work performs in different layers,” she says. “The most accessible are the ones that have to do with overt figuration, an in-your-face expression through gesture and scale. When you peel down, there are subtleties and color and symbolism, still quite universal but more embedded. And if you keep peeling down, eventually you’ll get to a level that is very close to my sense of culture – and very specific to that culture.”

For most of the past decade, Córdova has made her home in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, close to Penland School of Crafts, a place near and dear to her heart. But her soul resides a world away. She was born in Boston, where her parents were medical students; they returned to their native Puerto Rico for good when she was 6 months old.

The island’s omnipresent Catholicism gave Córdova her earliest sense of the power of the figure, and fostered her interest in magical realism. “My parents were very consistent in taking us to church. On Holy Friday, we would visit 10 churches, and my mom would light a candle in each one,” she recalls. During Mass, she would stare up at the statues of saints, profoundly moved by the sorrow, passion, and benevolence expressed in their faces and stances, the position of their hands, the folds of their robes.

“They drew so much out of me, so much empathy. But also they were intimidating, and they were sad, and they were grotesque, some of them, like the bleeding Christ,” she says.

Later, as an art student at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, Córdova became fascinated by how certain visual effects in religious iconography – the overlarge, glistening eyes of the statues, their smooth skin – were by design, if not really divine, meant to elicit a visceral response in the faithful. What would happen, she wondered, if such devices were transposed to a contemporary art context?

At university, she dabbled in painting, drawing, and printmaking before taking a course with Jaime Suárez, a leader in Puerto Rico’s contemporary ceramics movement. “He had a very free and fluid approach to the material.” Soon Córdova was “obsessed” with clay. “That it somehow captured so much of an imprint – not only physically but also the imprint of myself, the frequency of what I had inside – was really captivating.”

To develop her technical skills, Córdova went on to study ceramics at Alfred University in New York, and was committed to the figure by the time she earned her MFA in 2002. She also met and married fellow student Pablo Soto, a glass artist from Texas, whose parents, Ishmael Soto and Finn Alban, are both ceramists. Their friend Cynthia Bringle, the celebrated potter long associated with Penland, told the young newlyweds about the school’s three-year residency program for emerging artists. They arrived at Penland in 2003 and never left.

Today the couple live with their two little girls in a 1920s country bungalow, and work in a his-and-hers studio they built on a knoll behind the house. Penland’s executive director, Jean McLaughlin, speaks warmly of Córdova as an engaged, and engaging, member of the school community, always visible on campus – working with students, at the coffee shop with her daughters, speaking before a crowd at Penland’s annual auction about the power of the creative process.

“Each time I stand before one of her works,” McLaughlin says, “I think of the voice of the figure and the voice of the artist – each highly observant, each expressively wise – the eyes and hands saying something everyone wants to stop and hear.”

Córdova regards her life at Penland as a gift that has afforded her the space, serenity, and support to develop as an artist. Still, there’s a part of her that she says gets “paused” when she’s away from Puerto Rico and reactivated whenever she goes back for a visit. When the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico in San Juan gave her a solo show in 2009, she was “proud and terrified,” excited for her work to be seen and understood by an audience with a shared collective consciousness. The following year she did a series of pieces inspired by her search for “the epicenter of culture” on the island, which she concluded exists, ironically, “at the margins of society.”

While Córdova doesn’t want to be labeled a Puerto Rican artist – or a woman artist, or any type of artist, other than a compelling one – she does believe authenticity can come only from a deeply personal place.

“I’m not necessarily interested in being too generic. It’s important to anchor yourself in the specificity of your culture and your story.”

Joyce Lovelace is American Craft’s contributing editor.