Line by Line

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 2

I find that a craft gives somebody who is trying to find his way a kind of discipline. – Anni Albers1

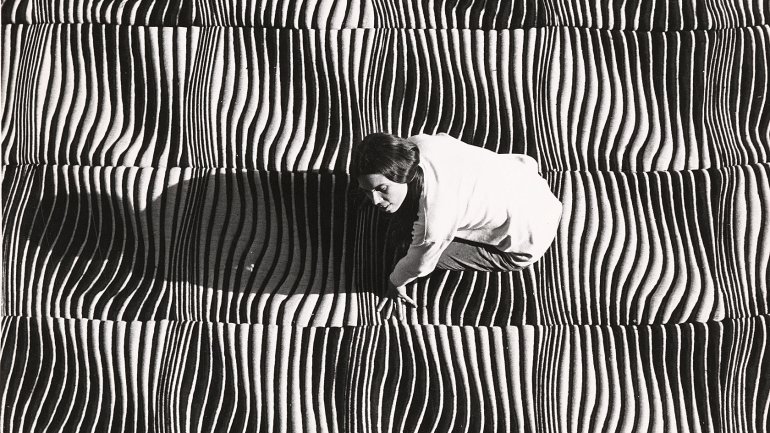

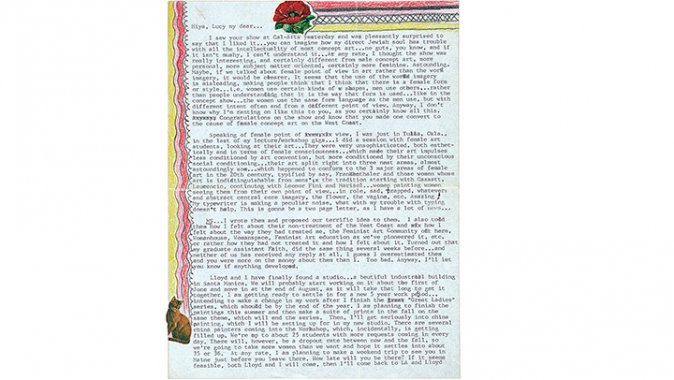

Craft is everywhere in the Archives of American Art. Take, for example, a midcentury photograph of Jackson Pollock trying his hand at a potter’s wheel in Springs, New York, or a circa 1990 snapshot of Sarah Mary Taylor hand-stitching a quilt at home in Yazoo City, Mississippi. Then there is Kay Sekimachi’s 1948 membership card for the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland or a 1973 letter to Lucy Lippard from Judy Chicago about an upcoming china-painting course at the Feminist Studio Workshop in Los Angeles. Documents such as these reveal stories about artists finding their way with craft. This is the lure of the archive.

Archival records contain key evidence – the who, what, where, and how of the art world. They help map the biographical details, economic circumstances, and technical advancements of artists. Researchers seek archives for these gifts of clarity, but archives can also be evasive, following their own logic, refusing easy assumptions about the ever-looming “Why?” They expose conflicting narratives and historical gaps. It is within these fissures that new questions about art, history, and culture emerge. With all this in mind, this essay explores how craft is represented in archival records. How can they help us find our way?

To begin, I’d like to introduce myself and the Archives of American Art, where I have worked since 2008 and where I found my own way to craft. The archives were founded in 1954 in Detroit, Michigan, by E.P. Richardson, then director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, and art collector Lawrence A. Fleischman to support the fledgling field of American art. In 1970, the archives became part of the Smithsonian Institution, with new headquarters established in Washington, DC. The archives’ current holdings are made up of more than 6,000 collections, including letters, diaries, and scrapbooks by artists, dealers, curators, and collectors; unpublished manuscripts of critics and scholars; business and financial records of museums, galleries, schools, and associations; photographs of art-world figures and events; sketches and sketchbooks; rare printed material, film, audio, and video recordings; and also, digital materials such as email and databases. The archives have also conducted more than 2,000 oral history interviews with artists ranging from photographer Dorothea Lange to collector Cheech Marin (yes, that Cheech, of the comedy duo Cheech & Chong).

American craft moments and movements are well documented in the archives. In a 1965 editorial for Art in America, archives co-founder Richardson wrote that the mission of the research center was to “collect basic source materials necessary for the study of American painters, sculptors and craftsman.”2

Craft is woven into the documentation of New Deal arts projects, such as the Index of American Design, and into the rise of modern design, as evident in the papers of Dorothy Liebes, Esther McCoy, Eero Saarinen, Florence Knoll, and others.

In 2000, Liza Kirwin, then Archives of American Arts’ curator of manuscripts (and currently its deputy director), led the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and the Decorative Arts in America. More than 200 artists – many considered pathbreaking leaders of the American studio craft movement – were interviewed, and dozens of their manuscript collections were acquired under the aegis of the Laitman Project. These resources evoked the possibilities and experiments inherent in clay, metal, fiber, wood, and glass, collectively articulating the very meaning of 20th-century craft.3

When it began, the archives were structured on existing models that focused on gathering disparate manuscript collections into one central location for easy access. Archivist and author Kate Theimer has compared the archives field to the mining industry, describing how “archives collected the raw materials – records and manuscripts – and ‘refined’ them, as one would a natural resource, by processing them and producing descriptions of them.”4 Trained scholars, the niche users of most archival repositories, would then transform these resources into secondary sources – books, exhibitions, and documentaries – for use by more general audiences. This workflow demonstrates the long-standing power of an archive as a keeper of cultural memory.

Over the past several years, the “archival turn” in both the humanities and archives professions has upended the presumption that archives are inherently neutral and authoritative.5 Archives are no longer understood as passive storerooms to be mined but rather as sites of knowledge production, even activism. The processes of acquiring, describing, presenting, and interpreting materials are becoming more experimental, collaborative, and attuned to historical silences and inequities. Similarly, primary sources are becoming more widely accessible online, from individual social media platforms (where, for example, users can scroll through Cindy Sherman’s Instagram feed) to the Smithsonian archives’ digitized collections, where users can page through Beatrice Wood’s glaze books.6

In this era of widely available and decentralized archives, even as the very term “archive” has become more nebulous, the research value of unique documents has continued to grow. In addition to being a site (physical and virtual), an archive might be deployed as metaphor, a category, or a process, much as craft is. In a 1968 oral history interview for the archives, German textile artist and printmaker Anni Albers recalled how “the limitations and the discipline of [weaving] gave me this kind of ... railing. I had to work within a certain possibility, possibly break through [it], you know.”7 For Albers, weaving was simultaneously a limitation and a support system. Her discipline helped her to transcend the system. Archival research is similar in that primary sources structure an established line of inquiry and also reorient researchers toward entirely new lines. The personal papers of studio craft artists offer a window into their deep engagement with materials. Compared to those of other visual artists, the papers of craft artists typically contain more voluminous documentation of workshops or apprenticeships in the form of snapshots and mailers and show how schools, such as Arrowmont, Haystack, Penland, and Pilchuck, have incubated intergenerational and interdisciplinary communities. Correspondence among friends, teachers, collectors, dealers, and curators elucidates these communities across space and mediums. Reflective documents such as diaries and artists’ statements simultaneously delve into the nitty-gritty of process and express irrepressible creativity. With this in mind, let’s follow a thread.

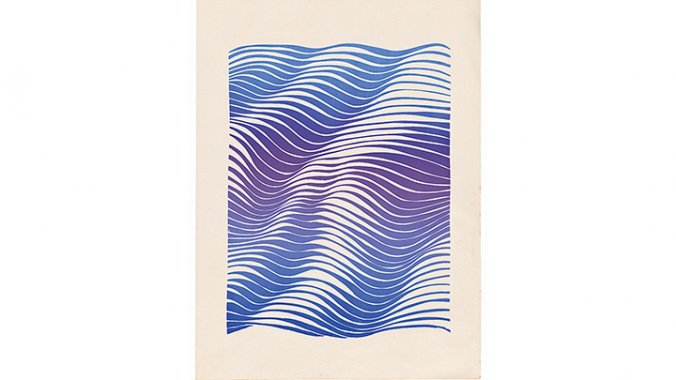

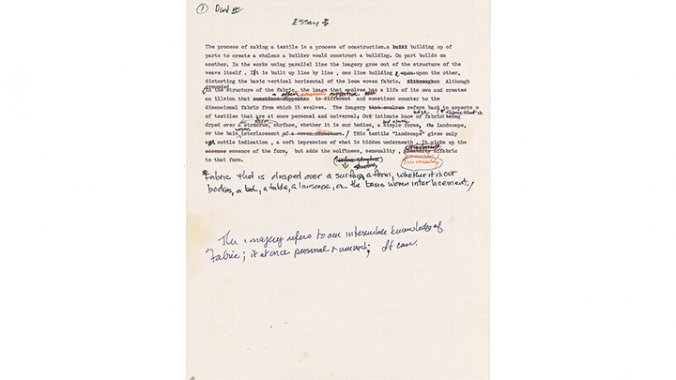

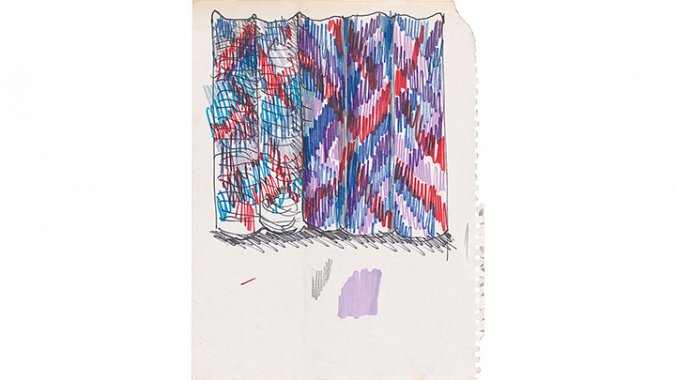

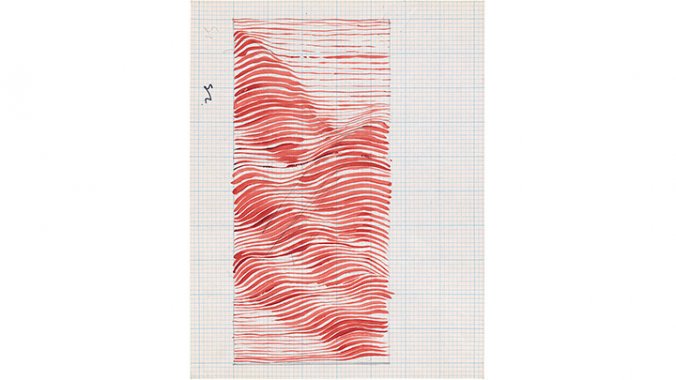

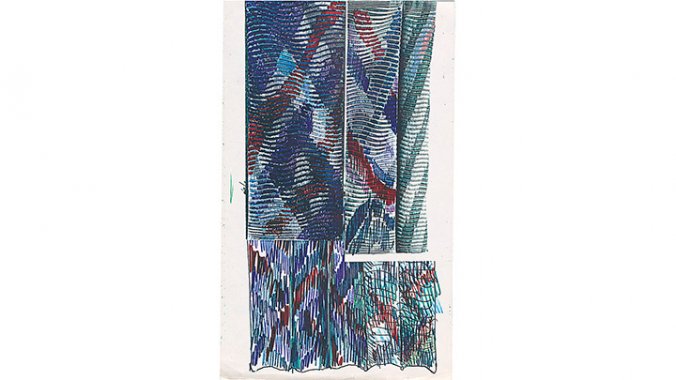

In a circa 1975 essay draft, artist Lia Cook outlines how she constructs a textile. “The process of making a textile is a process of construction … It is built up line by line, one-line building upon the other, distorting the basic vertical/horizontal of the loom-woven fabric. Although grounded in the structure of the fabric, the image that evolves has a life of its own and creates an illusion that is often supportive and sometimes counter to the dimensional fabric from which it evolves. The imagery refers back to aspects of textiles that are at once personal and universal.”8

Cook’s surfaces gesture toward, but ultimately do not reveal, the underlying structure of the weave. This reminds me of archival inquiry. Historical analysis is constructed – line by line – from the fragments, rumors, and distortions of evidence into a representation that is “often supportive and sometimes counter” but can never fully mirror the original moment. To be sure, this position is positive. Primary sources are catalysts for personal reflection. As they are imbued with a creator’s artistic idiom and personality, they also prompt profound feelings of empathy. This more reflexive approach underscores how the use of the archive adds nuance to a topic. Dear reader, this is where I ask for your help. For critical craft scholarship to flourish, its archives require users. My colleague, the archives national collector Josh T. Franco, states that “archives are inheritances. Their fate can range from dusty boxed-up obscurity to spectacular consumption. That is up to the inheritors.”9

As the current inheritors of craft’s histories, all of us – artists, family members, curators, collectors, archivists, and students – must plot our course(s) of action to ensure the vibrancy and relevancy of craft to future inheritors. We need to think through craft with primary sources, and then make our stories. These stories will, in turn, prompt a return to the archive. As this cycle picks up speed, it will constantly produce new insights. This intimate attention to the historical record will also improve the ways in which archives can challenge art world hierarchies and emphasize marginalized artists, mediums, and movements. Perhaps one of the most exciting prospects of archives is that they are never complete. We always have work to do.

To find our way, we must use archives as a kind of Anni Albers-like railing. This is an opportune time, given the broad accessibility of primary sources. Archivists love hearing from you. Visit local and regional manuscript repositories (e.g., a university’s special collections or a historical society) to discover new topics. Or visit the Archives of American Art, which has been steadily collecting the personal papers of studio craft artists for the past two decades. We have recently acquired the papers of Rudy Autio, Garry Knox Bennett, Paulus Berensohn, Karen Karnes, Marvin Lipofsky, Miye Matsukata, Don Reitz, Marjorie Schick, Mary Schimpff-Webb, and J. Fred Woell, among others.

Exhibition ideas, art projects, and thesis topics await you in our manuscript collections. You need only start by opening a box. This is the promise of the archive.

Read more from the fourth issue purchase issue

1. Oral history interview with Anni Albers, 1968 July 5. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

2. E.P. Richardson, “Editorial: How to Make a Time Capsule,” in Art in America, vol. 53, no. 4:21 (Aug. – Sept. 1965), 21. See also Garnett McCoy, “The Archives of American Art” in The American Archivist, vol. 30, no. 3 (July 1967), 445-451.

3. See Liza Kirwin, “Primary Sources for the Study of Studio Craft” in American Art, vol. 21, no. 1 (Spring 2007), 23-27; and Liza Kirwin and Joan Lord, “A Toolkit of Dreams: Conversations with American Craft Artists,” in Archives of American Art Journal 43, no. 1/2 (2003), 1-24.

4. Kate Theimer, “The Future of Archives Is Participatory: Archives as a Platform, or a New Mission for Archives” April 3, 2014, (accessed August 6, 2018), archivesnext.com/?p=3700.

5. See Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Shawn Michelle Smith, American Archives: Gender, Race, and Class in Visual Culture. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999); Maryanne Dever, “Archives and New Modes of Feminist Research,” in Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 31, no. 91-92 (April 2017), 1-4. Kate Eichhorn, The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013).

6. Kate Theimer, “The Future of Archives is Participatory.”

7. Oral history interview with Anni Albers, 1968, July 5. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

8. Lia Cook, draft of an unidentified essay, ca. 1975. Lia Cook papers, circa 1970 – 2000. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

9. Josh T. Franco, “Más Rudas Collective, 2009 – 2016 (An Archival Epilogue to an Epic Pachanga),” in Journal of Feminist Scholarship, 12/13 (Spring/Fall 2017), 38-53.