A Day in the Life of a Craft Reality Show Judge

Glenn Adamson, Head of Research at the V&A and a regular columnist for American Craft, is currently acting as head judge on a television show for the BBC.

The premise of Paul Martin’s Handmade Revolution is simple enough: Amateur craftspeople bring in an object they have made, to be assessed by a panel of experts. The format is based loosely on a British show called Flog It, which in turn is based loosely on The Antiques Roadshow, familiar to most American viewers. In both of those programs, members of the public bring an object in for expert evaluation. The suspense lies in the true identity of the artifact: Is it worthless junk or a priceless treasure? At the end of each segment an approximate cash value, assigned by a specialist, delivers satisfying dramatic resolution. The implication is that every household may contain an unrecognized masterpiece.

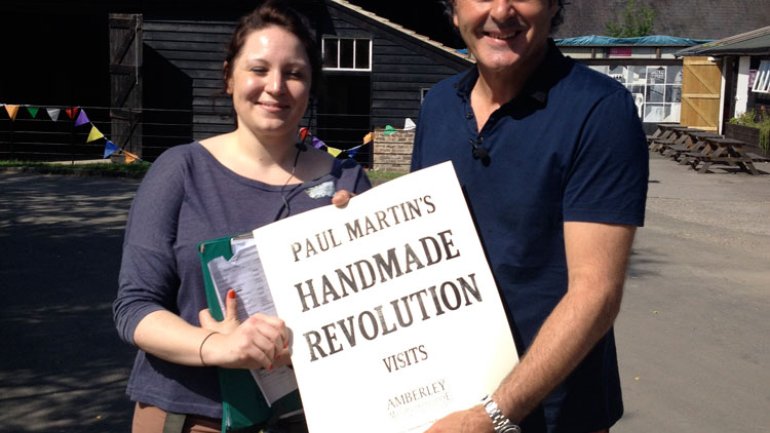

Paul Martin – a genial fellow who originally wanted to be a rock 'n' roll drummer (he grew up next door to Ray and Dave Davies of the Kinks) and has a pop musician’s natural charisma – has found fame across the UK as the host of Flog It. In August I participated in the first shoot for his new show, which is a sort of call to arms for craftspeople everywhere. The message is: You may not own a masterpiece, but you can make one! (This is Britain, however, so the tone is a little more understated than that: "Why not have a go?") My job as head judge is to lead a panel of three. For each show we consider five entrants, whose work ranges wildly in material, skill level, and conception. In one episode, we found ourselves trying to work out which we preferred among three leading contenders: a stone carving in the shape of a hare, a quilt made from fabric tinted in a washing machine, and a kinetic wooden clown sculpture. Apples and oranges look pretty similar in comparison.

It’s a tough job, but my co-panelists are terrific; and as a trio we’re at least as varied as the objects under scrutiny. My own role is to represent the Victoria and Albert Museum, which means projecting an air of authority, a knowledge of craft history, and a deep commitment to the creative process. The second judge, Mary Jane Baxter, is a milliner by trade. She is all charm, the friendly face on the panel, but ever ready with intelligent observations and helpful suggestions for improvement. The other panelist is Piyush Suri, a textile designer and entrepreneur who originally hails from India. He brings his business sense and a witty, acid tongue to the proceedings. Piyush is as close as we get to Simon Cowell, but even he strikes a mostly encouraging note with the makers. Finally there is Paul Martin himself, who acts as presenter. His job, as far as I could make out, is to emit boundless enthusiasm for craft. Looking up into the sky as the camera swoops above him, he praises the handmade as an antidote to dull mass production and exhorts the audience to rediscover traditional skills before they disappear forever. Only the most hard-hearted viewer is likely to be unmoved.

For a historian like me, participating in the show is an oddly familiar (as well as completely enjoyable) experience. In its atmosphere, the show conforms to the broad outlines of contemporary reality television. But its core message is descended from innumerable precedents - Walter Gropius’s proclamation in the 1923 Bauhaus manifesto ("architects and designers, we must all return to the crafts") or of course the writings of William Morris, the greatest craft guru of them all, whom Paul Martin name-checks in one episode. Seeking precedents for the show, you could go ever further back to John Ruskin’s Unto This Last (1860), Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854) or Thomas Carlyle’s Signs of the Times (1829), all of which outlined the need for a reinvestment in craft and self-sufficiency in order counter the dehumanizing effects of industry.

The idea of a "return to the crafts," then, is itself a venerable tradition. Yet the move to mainstream TV does entail a change in message, not just medium. Despite the incendiary term "revolution" in the program’s title, it is a gentle and almost entirely apolitical affair (reminiscent of the puzzlingly harmless phenomenon of "guerrilla knitting"). The atmosphere is light and joyful and focuses on personal development rather than social change. All finalists, regardless of skill level, are congratulated for their dedication and "passion," a word that is used a lot on the program. Only amateurs are allowed to participate, guaranteeing that the principal factor involved will be individual satisfaction, not economic gain. The message is that craft is a non-competitive, fundamentally life-affirming activity. This is perhaps most explicitly telegraphed by the fact that there are no winners on the show, only judges’ favorites.

The setting that the BBC chose for the first weekend of shooting, Amberley Museum and Heritage Centre in West Sussex, emphasized this gentle, pastoral tone. Amberley is a historic site – an old limeworks – which now has various demonstration areas for traditional crafts. As one of my PTCs (that’s Pieces To Camera, one of many fun technical terms I learned working on the show), I had the pleasure of speaking to John, an older man who volunteered at the museum. He’d spent his childhood in the wheelwright’s shop of his father and grandfather, and upon his own retirement he took up craft himself. The trade goes back in his family for many generations, and though it was never his own profession, he is deeply interested in this heritage and derives evident pleasure from following in his ancestors’ footsteps. He might be the last of the line, though. Unless some youngster rings him up to join on as an apprentice, he’ll be the last wheelwright in Amberley. Rubber tires are presumably here to stay, but it’s nonetheless moving to hear him describe the little variations in joinery that distinguished one village wheelwright’s shop from the next or watch him paging through a tinted catalogue of wagon designs akin to those his father would have made.

Stories like John’s make great television. Will they also make a real difference to the viewers? Many thousands of people – maybe over a million – will see Paul Martin’s Handmade Revolution, but how many will actually be inspired to start making? Many people have had the experience of cognitive dissonance while watching how-to television: watching a cooking show while eating takeout. But I have a pretty good feeling about Handmade Revolution. I’ve been studying craft from an academic perspective for 20 years. I thought I’d seen it all before. But I fell completely for the show’s finalists, so energized by their own pastimes. For each of them craft really had become a way of life, if not yet a paying job. The architecture student who took up jewelry while her studies were interrupted due to illness; the full-time caregiver practicing decoupage to find an outlet for her creativity; the eager young man hoping to break into animation as a model-maker: These are the stories behind the show. And there is something wonderful about giving them a media platform. Paul Martin may not be the second coming of William Morris just yet. But if he can’t get audiences at home to take up their tools and "have a go," then no one can.