Archiving a Landscape

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 2

“For the soul, then, beauty is not defined as pleasantness of form but rather as the quality in things that invites absorption and contemplation.” ~Thomas Moore, Care of the Soul

My work was born of a place. Specifically, it was born of a dry, hard-scrabble landscape surrounding a house on a hill off of a dirt road in Gallup, New Mexico, where I spent my formative years. As a child, I wandered and memorized that landscape, finding perfect sandstone perches, observing as fallen cactus limbs slowly evolved into dried, lacy skeletons, squeezing unearthed coal in hopes of making diamonds, taking in the smell of juniper and wet dirt after a quick downpour. My family and I moved east for my teenage years, and perhaps it was the sudden absence of my foundational landscape that sealed its value for me. To this day, that southwestern land, with its subtle shades of green and brown, evokes a feeling of rightness, and of home.

Careful observation of natural forms in their habitats has been a long-standing personal occupation and fascination, and these observations form the basis for my work. The forms that plants, stones, and shells take over time are infinite and varied. Tree rings show evidence of growth, drought, and fire. Holes in stones found at the ocean’s edge could be evidence of natural mineral decay or of sea creatures that have bored their way through to make their small, protected homes. Scarlet pimpernel plants are small and grow low to the ground. Their flowers are coral-orange; after blooming they evolve into tiny, perfectly spherical capsules that eventually dry and split into halves, spilling out minuscule brown seeds for the next year’s cycle.

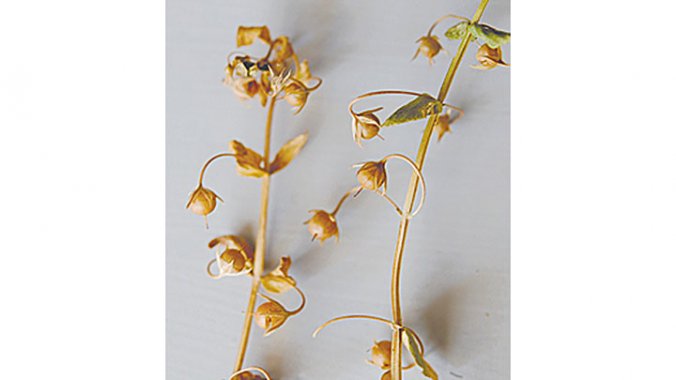

On close examination, what might have otherwise been overlooked can become an object of wonder and poetry. The gracefully downturned neck of the iris pod, emptied of its seeds, speaks of surrender, of life served in its rightful way, now nearly over. The golden nigella pod, standing proudly at the end of a long stem, is at once regal and thorny, hiding dark seeds and a fragile inner network, inviting one to marvel from a distance. Old pieces of driftwood piled on the banks of the Potomac River, smoothed over by time and the flow of water, invite wonder about their secret histories; perhaps they originated in many faraway places.

Observation of nature in varied environments, from desert to forest to tundra, brings an appreciation for both the amazing variety as well as the striking commonality of natural forms. Botanical specimens such as the devil pod (also known as a goat head), with its odd, bat-like appearance, are a wonder of evolution. They are hollow, black, and fierce in their appearance. Mahogany capsules are large and amazingly intricate, with a thick, woody outer layer and a thinner, yet still tough, inner layer; they open in sections to expose perfectly nestled seeds. Once freed, these seeds can fly on papery thin tails to the ground, leaving the exposed innermost center, an elongated oval with a ribbed tip. Just as amazing as these geometric marvels are the similar patterns to be found across species. Spirals can be found in grapevine and sweet pea tendrils, in the growth patterns of cacti, certain other succulents, even in shells. Star formations exist in sand dollars, in the opening pattern of many seedpods, and in the opening holes of the blue gum eucalyptus pod.

The natural materials I collect for my jewelry and sculptural works are organized and stored by place and by time. Items collected over decades are sorted and stored in various boxes or pressed in spine-stressed books. Reviewing my collection as part of my creative process becomes both a meditation on form and a survey of memory and personal history. In one old box I find cottonwood pods from a tree that stood next to a little restaurant with excellent Frito pie near Georgia O‘Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch. It was a memorable find, collected many years ago at a time when my work was just beginning to evolve into its current form. In another box I review a collection of old shells from Vancouver Island, originally shaped like cones but now so weathered they are lovely white ovate rings. They were found near a large fallen hollow tree where my husband, young son, and I sought refuge during a coastal downpour. Each item, whether found in colorful bloom or discovered cracked and old in a pile of debris, carries a story of its own existence, as well as a piece of my own. My collections of natural specimens remind me of places I’ve lived or visited, significant life chapters, and small moments that might otherwise have been forgotten. It is a great pleasure to pore over my collections of items and memories, looking for objects that will contribute to the essence of the feeling or dynamic I want to capture.

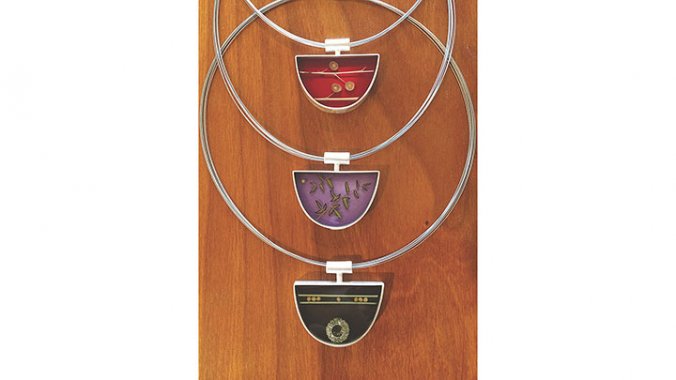

In the spirit of a child discovering a glorious pebble, it is a great joy for me to share my observations and creations with others through my work. In this sharing, I have met many fellow explorers. We compare notes on plant names, on varieties of galls and poppies, on native versus invasive species in different parts of the country. I am honored to receive materials in the mail from some of these others, sometimes to make commissioned work, other times purely because the sender wants to share a special find. Items I’ve been fortunate to receive include a box stuffed with amazingly varied dried mosses and lichens on twigs from Texas; purple sea anemone spines found on the island near where Amelia Earhart’s plane is thought to have gone down; a pressed clover bracelet, made on a first date and secretly saved for a special gift years later; dried flowers from the last garden of a deceased loved one. It’s my honor to be the holder of meaningful objects for others, and at times to create pieces that serve as memory objects for them of places, times, and relationships. The natural objects I collect serve as the raw materials for my jewelry and sculptural work. I plan my compositions over days of slow deliberation, examining and dissecting new and old materials, exploring form, gesture, or story. The compositions are then suspended, using dyed resins within small containers made of silver, wood, or steel. These containers serve as frames of focus. It is work that is made with the intention of sharing, and when pieces find new homes, I often feel a satisfying sense of catch-and-release.

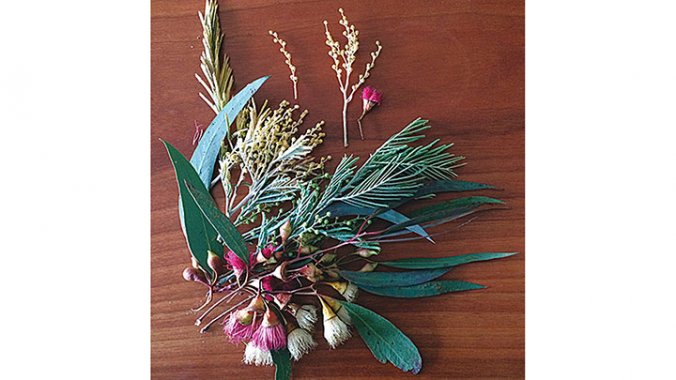

I currently live in Ojai, California. It’s a beautiful town of about 8,000 people, surrounded by mountains, hills, and orchards. The nearby hills are usually covered with live oaks, chaparral, wild grasses, lupines, and yucca. Wild fennel plants grow in abundance, their fine fronds tasting of sweet anise. The land is both rugged and fertile, with a Mediterranean climate that feels like an odd mix of tropics and desert.

From my studio I look out on the northern hills, watching as sunlight moves over crags and valleys through the day. I venture onto nearby hiking trails as many days as I am able, glad to have such immediate access to a world in which nature is so vast, wild, and encompassing. Over the years I have come to memorize which rock signals the proximity of my favorite coffee fern, the time of year the mustard flowers evolve into long stems holding tiny, narrow seedpods, which eucalyptus trees produce the pods that look like small perfect vessels, and when they turn from lime green to terra-cotta brown. Even on days when I embark on a hike with the express purpose of exercise and forward motion, an unusual detail on a twig will inevitably catch my eye. A second’s pause can easily extend into minutes of absorption into the details of a small area.

The Thomas Fire began on the evening of December 4, 2017, when two wildfires that started just east of Ojai merged and spread with explosive force. Fueled by historically strong winds, the fire raced across dry terrain, at times traveling at speeds of an acre per second. My family and I evacuated quickly. Over the following days we watched with grief, fear, and desperate hope as the fire spread west and north, threatening our town on every side. Firefighters were battling 70 mph winds, and containment was close to impossible. Smoke filled the air for many miles, darkening the sun and staining it red.

On the night of December 6, neighbors who had remained in town saw flames approaching at the end of their street, only blocks from my home and studio. We anticipated the worst, and watched the fire map through the night. Through the ingenuity and true heroism of local and national firefighters, as well as a miraculous few hours of shifting winds, most of our town was saved from what could have been even greater destruction. Tragically, the Thomas Fire destroyed more than 1,000 homes and other structures, covering 280,000 acres over the weeks that it burned. It was a time of immense loss for many. But amid the disaster, a fierce community spirit was also ignited, with neighbors coming together to lend support, information, muscle, and always to share stories.

Returning home after days absent was both a relief and a devastation. Through smoke-filled air, I encountered a land that was scorched in every direction, looking more like the moon than the land I’d come to know. The contrast between the green in the areas that had been saved and all that had burned around it was profound. Ash was so abundant in places that it almost looked like snow. Trails were closed, and air quality was in the toxic range for weeks. When it was finally safe to walk the nearby trails, I found that most of the areas which had grown so familiar were completely altered. Trees were blackened and leafless, evidence of the plants that had once thrived was nonexistent, and the vast, exposed earth was notably charred. I discovered remains of small animals apparently caught as they fled, overcome mid-stride. Never in my life had I experienced an environment that was so reflective of a single event in time.

Observing as natural process takes its course in the weeks and months after the fire, I have been deeply interested in which plants have returned, which have not returned, what has moved, and what is new. My favorite coffee fern did not grow next to the boulder this year, but some wildflowers that were new to me appeared in its place. I found my fern growing in an altogether different area. Seeds must have somehow migrated, traveling by wind or water during and after the fire, a mysterious process to me. The green that emerged in the hills after rains was deep and vivid, emerging in stark contrast to the still-darkened land. Charred live oak trees that had looked as if they would forever stand in stark silhouette began to sprout leaves, creating a striking reminder that growth can happen even after the ravages of fire.

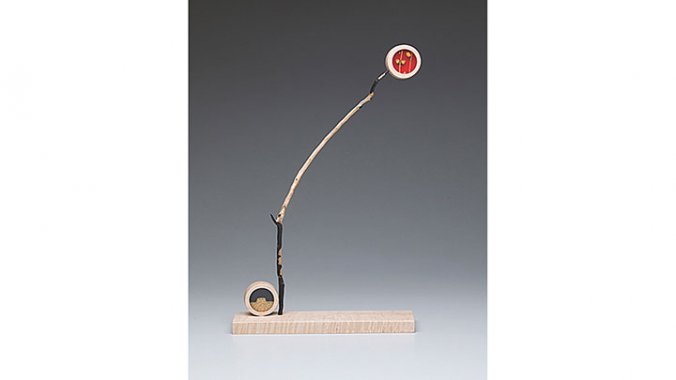

My creative process has become a crucial vehicle in my efforts to digest and make sense of all that has happened since the fire. Boxes of locally collected wild stems and fragile pods have become precious holders of before, as I wonder what will continue to come after. Singed branches and charred rocks found in my explorations after the fire reflect the awesome forces of nature, evidence of both destruction and survival. With an awareness of how the community’s sense of home has been altered on so many levels, I find myself using materials from the surrounding land to create pieces holding themes of shelter, vulnerability, and change.

In an environmental sense, periodic fire is good for the land. To know this and to witness this are two very separate experiences. As time passes, the land no longer solely reflects the single event of the fire but begins to incorporate the story of what comes after. Many years from now, overt evidence of this event will be minimal, recorded mainly in buried layers of earth, and in the rings of trees. The landscape will continue to evolve from here, and I look forward to continuing my own version of archiving this brief chapter in its evolution.

Read more from the fourth issue purchase issue