Zawi Chemi Shanidar, in northeastern Iraq, is home to the earliest known site for the domestication of sheep. Evidence at the proto-Neolithic site shows that sheep were domesticated at the beginning of the ninth millennium BC, although domestication may have occurred earlier among nomads, who then brought their knowledge of shepherding to the people at the settlement. In the first phase of the domestication of sheep, people moved from hunting animals in the wild to keeping them in pens for slaughter later on. A second phase in the domestication arrived at around 4,000 BC, when people in Mesopotamia realized they could extract materials from their animals other than meat and hides. Kept alive, they could provide secondary products: milk, wool, and strength to pull the plow. As people discovered they could get a steady supply of cloth from live sheep, the wool on these sheep’s backs changed in character. Wild sheep, and the earliest domesticated sheep, were hairy, but by selective breeding practices early domesticators created breeds that were woolly.

Wool in Wyoming

The process of breeding sheep to improve their wool has been with us ever since. It entered a new phase in the 20th century United States, when sheep breeders were tasked with meeting the needs of an industrialized society that mechanically processed its wool into thread and fabric. The University of Wyoming in Laramie—the only university in the country to offer a PhD in wool—was for a time the epicenter of this effort. The university’s Wool Department was created in 1907—when the state of Wyoming was just 17 years old and home to more than six million sheep and fewer than 150,000 people, a ratio of about 41 to 1—with the goal of improving the quality of western fleeces.

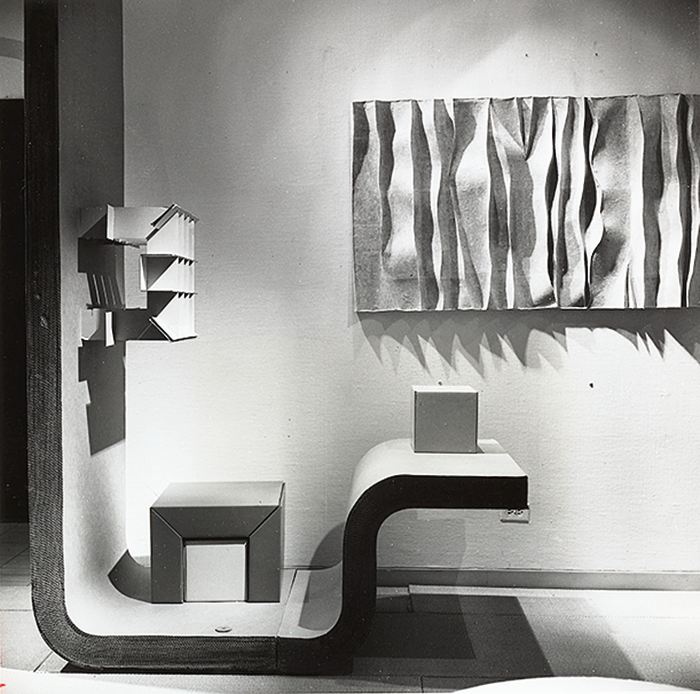

In the late 1930s, the USDA tasked the UW Wool Department with using its Wool Laboratory—a small pilot plant for scouring wool that would grow into a semicommercial operation—to develop federal standards for wool fiber, particularly as they pertained to fiber diameter, length, and shrinkage. The ones they developed would determine labels we see on wool products, so that fabrics marked “Super 100’s” were comprised of wool fibers with an average width of 18.75 microns or finer; while “Super 250’s” indicated 11.25 microns or finer.

Access to plentiful grass on the open range alongside strong wool and lamb prices created Wyoming’s first major sheep boom in the 1880s. Wyoming sheepherders competed for grass with cattle ranchers, and “away from the settlements the shotgun is the only law, and sheep and cattlemen are engaged in constant warfare,” Wyoming banker Edward Smith testified before Congress in the early 1880s. An 1897 tariff on Australian wool started a second boom, and by 1900 Wyoming had more than five million sheep. As grass became scarcer, conflicts escalated. These conflicts were brutal. In 1905 masked riders rode into a sheep camp in Big Horn County and shot, dynamited, or clubbed to death four thousand sheep, burning the herder’s sheepdogs alive. Nevertheless, sheep herds kept expanding. By 1908, Wyoming led the US in wool production.