Wearing the Truth

Wearing the Truth

The artist portrayed in Madame Beauvoir’s Painting, 2016, a photograph from the Rewriting History series, is attired in a gown made of paper. She paints a formerly enslaved man whose back bears the scars of brutalization. Photo by Fabiola Jean-Louis.

Jean-Louis in her studio. Photo by Aundre Larrow.

Jean-Louis’ handmade garments tell stories of the transatlantic slave trade and its aftermath. They also tell stories that center and empower Black lives—specifically those of Black women—and are imbued with elements of Vodou, powerfully grounding the artist’s Haitian identity and spirituality in each piece. Working across sculpture, painting, and photography, Jean-Louis performs her own kind of magic through her materials as she builds her ensembles with paper, not fabric, which she hand-paints. “Everything starts out with white paper,” she says. “I’m constantly inspired by the material. Every time, I push it even more to see what I can do with it.”

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art approached Jean-Louis to create an artwork for its new period room, a space rooted in Afrofuturism, the artist responded with a sculptural dress designed for war. The room, called Before Yesterday We Could Fly, debuted in November 2021. It features new commissions alongside collection objects that respond to the history of Seneca Village, a 19th-century Black community that was displaced to make way for Central Park. “I was thinking about the kind of rage and upset that causes,” Jean-Louis says. “[Designed for] a Black queen, the outfit is a rallying cry to speak on a revolution and on the need to prevent Black bodies from constantly being moved out.”

Ornamented with 24-karat gold, the dress features an hourglass silhouette based on 19th-century garments and latticed bishop sleeves that evoke armor. Entwined serpents wind along its mosaic bodice, portraying flowers, which symbolize offerings to Ezili Dantor, the loa, or spirit, of vengeance in Haitian Vodou. To create this battle dress, Jean-Louis blended paper into a malleable claylike pulp, then dried and baked it into tiles that she could arrange into designs. The resulting pattern “deals with my idea of Black experiences, the mosaic of Blackness,” she says. “This was a design I created from imagination to talk about my Haitianness, my Blackness, and my spirituality.”

The result is a garment that is also “a spin on an altar,” she added. Existing in its own magical reality and a space of its own time, the dress marks for Jean-Louis a new generation of garments.

“Everything starts out with white paper.”

—Fabiola Jean-Louis

ABOVE: Before Yesterday We Could Fly, the Metropolitan Museum’s speculative period room celebrating Afrofuturism. LEFT: Jean-Louis’ contribution to the period room is a garment for an imagined 19th-century Black queen that she designed “to talk about my Haitianness, my Blackness, and my spirituality.” Photos courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Histories Revealed and Recast

The stories Jean-Louis confronts in her work originate from the transatlantic slave trade and the enduring racial injustices and trauma of what African American studies scholar Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlife of slavery.” In Rewriting History, cruel images emerge that speak to the brutalization of Black bodies and the circulation of such visuals over centuries. A portrait reinterpreting a Thomas Gainsborough painting depicts, in the distance, white men raping a Black woman. A bronze paper dress features a stomacher, a decorated triangular panel of a corset, that reveals a lynching. Jean-Louis insists on depicting this violence because it is real: “I decided early that I would become a visual activist, and that meant showing things that were going to be very uncomfortable—not only for me, but for other people.”

Yet, while acknowledging these violent histories, Jean-Louis also adamantly generates beauty. Take Madame Beauvoir’s Painting (2016), a photograph of a woman painting a formerly enslaved man known as Gordon, and depicting his scourged back. Here, Jean-Louis designed the woman’s garment so the woman looks “like a flower, almost—something beautiful and soft compared to the harsh, traumatizing whip marks.” In her sculptures, she also adds elements of luxury through her choice of embellishments, such as Swarovski crystals or lapis lazuli, which symbolizes gods and power as well as spirit and vision. “I was trying to find a vehicle to carry these ugly truths,” says Jean-Louis, “and fashion was going to help me do that.”

In the photograph They’ll Say We Enjoyed It, 2018, Jean-Louis reinterprets a Thomas Gainsborough portrait. An elegant 18th-century woman in a paper gown poses with her lapdog; in the background, white men rape a Black woman. Photo by Fabiola Jean-Louis.

Portrait of an Artist

Jean-Louis has used style to assert her voice since she was a teen growing up in Brooklyn. She began wearing corsets at 16 as part of the 1990s New York goth scene; she also became a professional dominatrix. An immigrant from Port-au-Prince, she often felt out of place in the United States. “I became too Black in some circles, and not Black enough in others,” Jean-Louis recalls.

Her love of fashion led her to the High School of Fashion Industries in New York. Later, she studied medicine at Florida’s Nova Southeastern University but dropped out, partially due to academic pressures. In 2013, she began taking photographs of herself in surrealistic scenes: floating through rings, as if in mid-teleportation, or dancing from puppet strings, her balancing act alluding to how Black women have historically been controlled or manipulated. “I really leaned into art again as a form of therapy,” she says. “I started scrutinizing my Black identity much later on in life. I wanted to find more of myself, my own voice, so I would know what I really wanted to say.”

“I was trying to find a vehicle to carry these ugly truths, and fashion was going to help me do that.”

—Fabiola Jean-Louis

Rest in Peace, 2018, a life-size paper dress ornamented with an atrocity. Photo courtesy of Fabiola Jean-Louis.

While establishing her photography studio, she was keen to bring fashion into her art and began constructing paper dresses. Initially, the material was a cost-effective option. “Not having access to fabrics, not being able to afford to rent costumes for photoshoots, I was forced into that space of creativity,” she says. “What started out as a necessity to bring my visions to life eventually became my style.”

Material and Spiritual Strength

Nowadays, making a dress takes at least three months. Using four paper types, including a highly fibrous Korean handmade paper, she constructs a skeletal armature, petticoats, beads, and neckpieces. She paints details with pigment powder, alcohol ink, and acrylic, and uses wood glue, with some sewing, to bind her handiwork. “I’m really enjoying sculpture right now,” she says. “There have been a few small and big successes that I’ve made in the process of working with paper, and I want to keep exploring those. It’s about creating the hand memory, really holding on to things I’ve learned.”

Altar Shrine, 2021, 20 x 20 x 5 in., made of clay-treated paper and adorned with 24k gold, labradorite, dried flowers, brass, and Swarovski crystals, expresses Jean-Louis’ blend of Black consciousness, the Haitian religious tradition, and a keen historical sense. Photo by Fabiola Jean-Louis.

In Jean-Louis’ hands, paper, often perceived as fragile, becomes a supple tool to affirm the inherent dignity of Black lives amid the persistent spectacle of Black trauma. Alluding to records and documentation, the material also underscores the central idea of Black authorship in her art. If it is worn, those wearing it and animating it are always Black. “I was clear that I would only put Black women in my work, because [individual portraiture] was a space we weren’t taking up enough,” Jean-Louis said. “If you’re Caucasian, you can be a fairy, this magical being. Rarely are Black women depicted in such a delicate, magical way. Somebody needed to do that, and it needed to be a Black woman.” In Rewriting History, sitters are protagonists in stories from which they’ve been erased; they enact, in spaces historically inaccessible to them, a resolute act of reclamation. Last April, the series was acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Library, assuring that these narratives attain further longevity as research tools.

In a self-portrait, Jean-Louis reimagines the Madonna in Paradise Lost, 2020. The photograph is part of her Atonement series, an engagement with spirituality and Catholicism. Photo by Fabiola Jean-Louis.

Paper continues to lead Jean-Louis in many directions, across the mosaic of her own sense of self. She has been developing a series titled Atonement that explores her relationship with spirituality and Catholicism through portraits of herself and others wearing paper garments. The Met commission also provoked a desire to depict an all-paper installation that presents a deeply personal rendition of the Haitian Revolution. Her vision includes full-scale altars—magical sites of remembrance and ancestral connection that are both sacred and protective. “What I’m really talking about in all of my work is a certain type of spirituality that I believe is at the center of Black identity,” Jean-Louis says. “I’m tapping into the roots and magic at the center of strength.”

fabiolajeanlouis.com | @fabiolajeanlouis

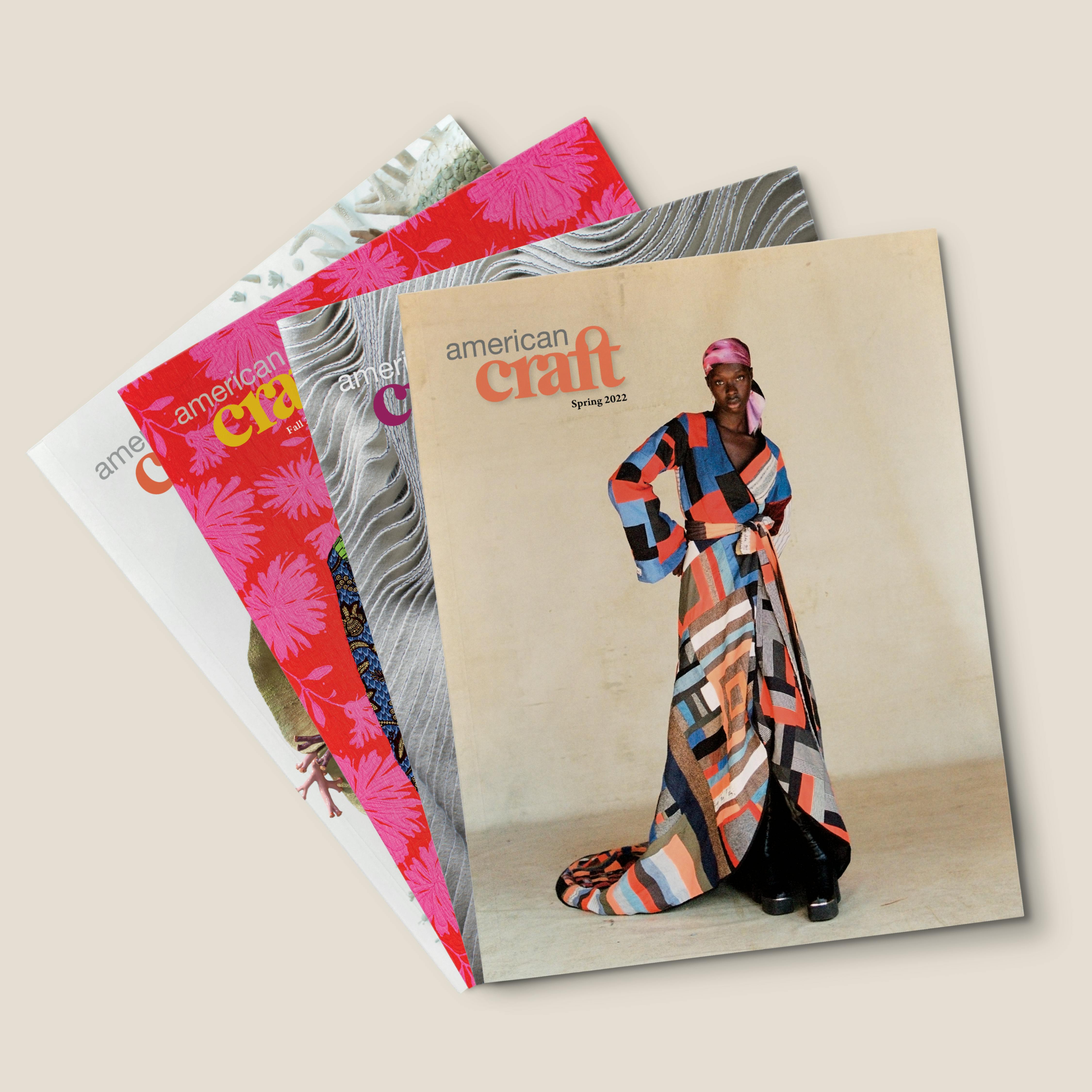

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.