From Sheep to Blanket

From Sheep to Blanket

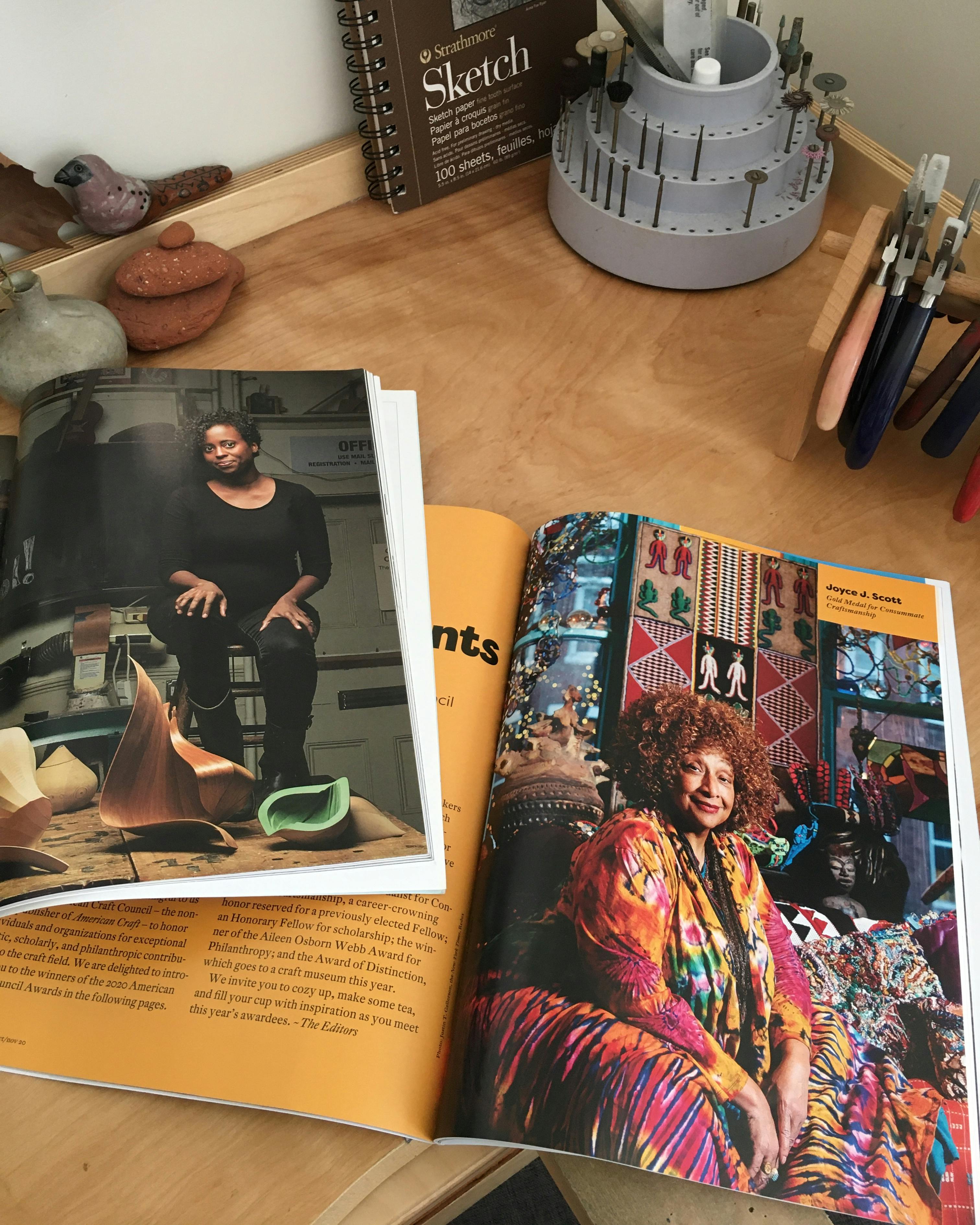

Photo courtesy of Nordt Family Farm.

The farmer placed the lambs in a pen in the bed of the truck, and Nordt headed south on Interstate 95. “Driving home, I thought, ‘What am I doing?’” she recalls. “It was both total excitement and also, ‘Is this the craziest thing I’ve ever done?’”

Three hours later, the live cargo arrived at the Nordts’ 400-acre farm along the James River southeast of Richmond, Virginia. “As soon as the lambs jumped out of the truck into the pasture, the horses started chasing them,” Nordt says. One lamb had a broken leg. Luckily, her husband, William, could use his skills as an orthopedic surgeon to fashion a splint for the injured lamb.

“There’s been all kinds of crazy learning experiences since then,” says Nordt, whose flock now rests at 36 sheep from a high of 50.

As a teen, Nordt couldn’t wait to leave the Virginia farm she’d grown up on for a life of fashion and glamour in a big city. But after studying fashion design at Virginia Commonwealth University, she realized that although she loved fabrics and constructing clothing, she abhorred the industry’s reliance on trends and disposable garments. Meanwhile, the farm life of her youth beckoned.

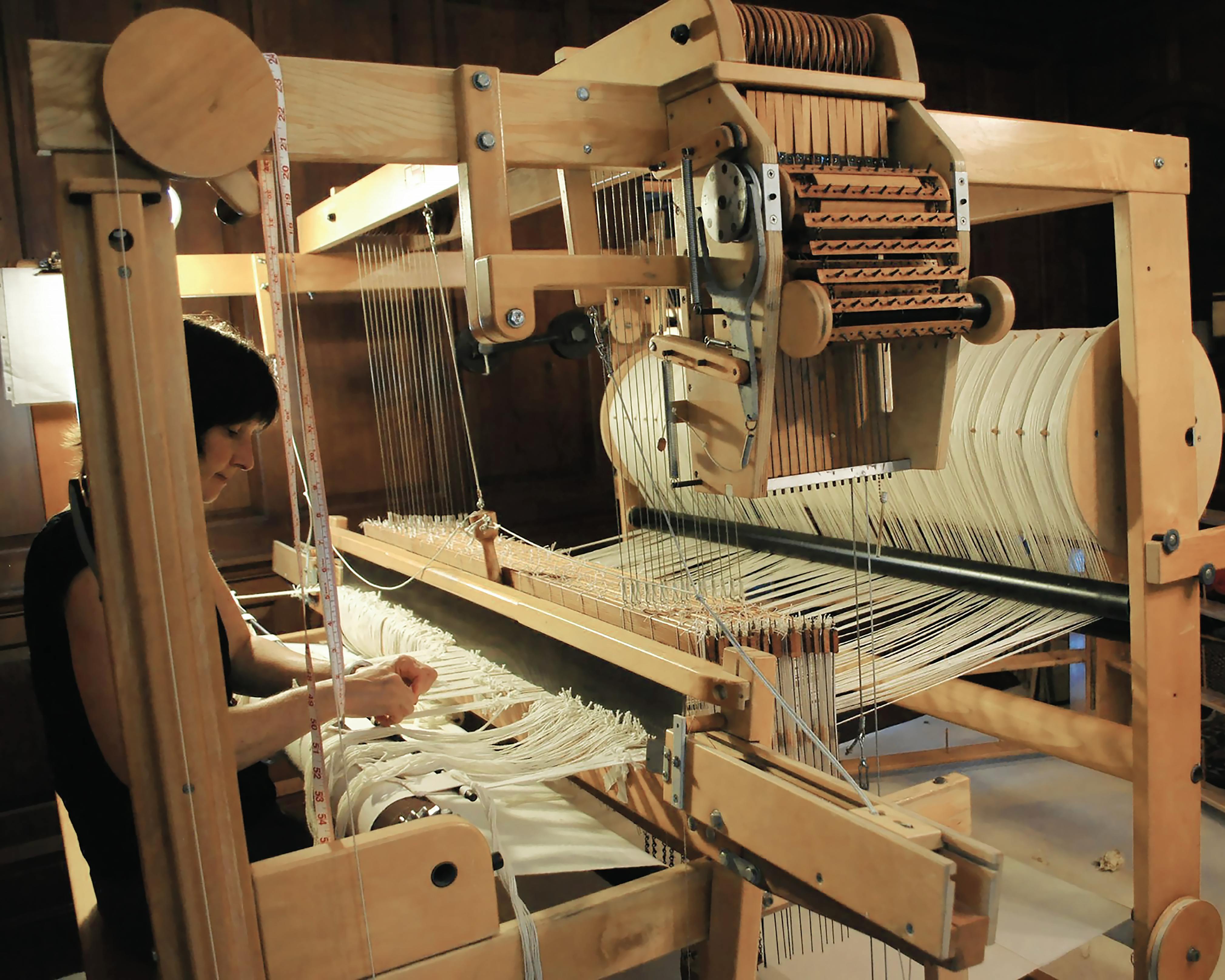

A chance peek into a room filled with looms drew Nordt to weaving, and she took every class in the subject she could. When her father said he wanted to give her a car as a college graduation gift, she asked for a 16-harness loom instead. After a long pause to raise three children (she also owned and ran a women’s shoe store in Richmond for a decade), she returned to weaving full-time and still uses her father’s gift.

Nordt focuses on making throws and baby blankets, which she started selling in 2011. She numbers each blanket, and is soon to top the 2,500 mark.

She keeps her designs simple and prefers the sheep’s natural hues of white, gray, and brown, with muted accents of yellow, green, and red yarn that she hand-dyes using natural sources.

“I consider myself a production weaver,” she says. “All of the design and color comes in the weft, from side to side. That allows me to save time and make a product that’s affordable to the consumer. That’s the sweet spot.”

Nordt weaves nearly every day.

“When I sit myself down at the loom, to this day I feel like this is exactly where I need to be,” she says. “The rhythm of locking myself into the loom feels like coming back into my heartbeat.”

Merino sheep,  originally from Spain,

originally from Spain, are known for their fine, soft wool. Weaver Dianne Nordt

are known for their fine, soft wool. Weaver Dianne Nordt

southeast of Richmond, Virginia. Her 36 sheep forage on clover and other natural grasses,

southeast of Richmond, Virginia. Her 36 sheep forage on clover and other natural grasses,  supplemented with hay

supplemented with hay  and grain. The sheep are

and grain. The sheep are  sheared every February by internationally known blade shearer Kevin Ford.

sheared every February by internationally known blade shearer Kevin Ford.

The average fleece produces eight pounds of wool,  which reduces to four or five after washing. The wool from one sheep can produce about four

which reduces to four or five after washing. The wool from one sheep can produce about four

to a mill in Michigan. There it’s cleaned, carded, and spun—a yearlong process. When the spun wool is returned,

to a mill in Michigan. There it’s cleaned, carded, and spun—a yearlong process. When the spun wool is returned,

manual loom to weave throws and baby blankets.

manual loom to weave throws and baby blankets.

She relies on natural colors supplemented by dyed yarn.  She dyes her own yarn using natural sources, such as goldenrod

She dyes her own yarn using natural sources, such as goldenrod -Golden-Rod-1_CMYK.png?fit=max&w=840&auto=compress,format&cs=srgb) and black walnut.

and black walnut.  She washes each piece and hangs it on a clothesline to dry.

She washes each piece and hangs it on a clothesline to dry.  She then hems the borders by hand. With each blanket she ships off, Nordt includes a personal handwritten note

She then hems the borders by hand. With each blanket she ships off, Nordt includes a personal handwritten note  and a photograph of her woolly flock.

and a photograph of her woolly flock.

nordtfamilyfarm.com | @nordtfamilyfarm

ABOVE: Photos of shearing (two) by Jeff Glotzl. Map by FogueraC / Wikimedia Commons. Hay bale photo by Tony Webster / Flickr. All other photos courtesy of Nordt Family Farm.

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member for a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.