Returning

Returning

Randy Takaki’s studio, where his figures stand awash in natural light. Photo by Lisa Hartmann.

We were on a 10-day photography retreat on the Island of Hawaii in March 2008, and it was the first day. A group of us—six photographers and our teacher—piled into an SUV to begin our tour and to meet some of the local artists, including the late Randy Takaki (1952–2016), to see artwork, explore landscapes, and make photos. I was expecting to shoot some images, then make my own artwork in response—a familiar workshop routine.

Takaki’s studio was an old and unassuming converted garage outbuilding—rusted corrugated metal siding with a moss-covered metal roof—in the middle of an incredible riot of plants near the rain forest slopes of the Kilauea volcano, Hawaii. As we were walking along the path to it, I noticed a wire sculpture sitting under a tree: a human body formed in chicken wire. I thought it was lovely, but it didn’t prepare me for what I would see in the studio.

We walked in, and Randy quietly welcomed us, but there was no presentation, no “this is my work, this is my philosophy.” We were left to ourselves to experience what we were seeing, simple figures that have been called “guardians” by some, though Randy didn’t give them a name.

The figures were made of wood, stone, and old wire fencing—one was even drawn with motor oil on plywood. They were one-foot, two-foot, nine-foot, life-size, six inches, a quarter of an inch—all intentionally placed with remarkable care. Every one of them had their heads bowed slightly and embodied gestures that evoked reverence, meditation, presence. There were hundreds of them.

Randy Takaki’s figures range from a quarter inch to about a story high. This carved wood “guardian,” with its head bowed, stands about eight feet tall. Photo by Lisa Mauer Elliott.

When I looked at figures, it felt as if everything fell away from me: any idea of myself, why I was standing there, what I was supposed to be doing with myself or with my body. Tears started flowing. I felt grief, love, undoing. Yes, it was an undoing, and it was holy.

I had this very peculiar sense of being completely naked, seen, and of accepting my own humanity at its core, with no complications, because everything else was just . . . gone. It was an encounter with the sacred; like walking around as a soul—difficult, beautiful. Like touching grace, touching the essence, touching holy ground. Like being loved and accepted, in the deepest, simplest way. It felt like forgiveness. Like being opened, by the gentlest of hands, bowing heads.

The figures were weeping, reverent, present. They seemed to know and accept all, without complications. Like sweet music that rearranges your cells and aligns you to what is and always has been whole. And I was cleaned out. A death. A rebirth. A resonance with the divine. I was understood, known by them, without any explanation needed. All the angst, confusions, and uncertainties were removed for a time, and armor fell away. I was washed by the tears clean out of my skin. I was home.

What he did isn’t easy to sum up. Part of it, I think, is the sheer beingness of these forms, and his recognition of that beingness.

After a while, I thought to myself, I have got to pull myself together. I have to stop crying. This is ridiculous. It’s our first day! I have to make photographs. I’m supposed to be making work. So I started wandering around, and now and then I would take a moment to make a photograph of one of the figures. I wanted to say “Hello” to them, but I had no idea how to do that in the state I was in.

Takaki would ask for permission from found materials, such as this tree stump, before claiming them and creating his figures. Photo by Lisa Hartmann.

To try to break the spell, I walked outside to the back of the building where there was a massive wooden water cask, part of a rain catchment system, that had a gorgeous, rusty metal wrap around it. I added a moss-covered branch and took some photos of the composition, but still I couldn’t figure out how to regain any semblance of what we call “self-possession”—to come out of this state of no words, all tears, grief, recognition, awe, and of being seen the way you’re seen when someone perceives your very essence and says yes to that essence—yes to you, just as you are.

Something about what Randy Takaki did in making that work entered into me for good.

What he did isn’t easy to sum up. Part of it, I think, is the sheer beingness of these forms, and his recognition of that beingness. I came to learn that one of Randy’s core practices was about permission—asking anything that he was touching whether or not he had permission to complete the form he had in mind, and listening for the answer.

This listening is deeply respectful. You can feel its presence in the most massive figures and in the ones that are a quarter of an inch high. In many of them you can see the texture of the wood and how it has cracked: a sense of time and of the profound age of the materials. Randy understood what it is to be the means for something to come into being and not the “master maker.”

Outside Takaki’s studio building, three 4 to 5 inch stone carvings sit quietly among moss and leaves. Photo by Lisa Mauer Elliott.

He created so many of these figures, thousands of them—offering his hand and his skill to help these forms emerge over and over and over again. Thousands of encounters with his materials in which he kept saying, Yes, I’ll ask again, and again. There was no forcing. He told me that sometimes he would dream about the figures. And he told me that staying with them as he created them had meant staying with the feeling of longing.

That was the beginning of something in my own work that has to do with seeing more deeply into the materials that are in front of me, with wanting to express the aliveness in everything. There’s a word in Japanese, inochi, that means the life essence that is in everything. In rocks and in trees. In ants. In water. In air. In wind. You know it when you see it, the something within that’s alive.

I live with two of these figures: one that I bought from Randy when I was there, and one sent to me several years later by a dear friend I’d met on that trip. They sit quietly on my bedside table, felt and loved daily. Randy’s forms are a distillation; a partnership between; a gift; a path of returning to ourselves. And his figures are little guides for me: they remind me, as my encounter with Randy reminded me, that our work as artists is all about returning.

Returning again and again to the work, as Randy did, as we all do, in order to distill our work down to its core. Returning to our essence as beings in this world rather than mere nodes in the systems we’ve created. Returning to the wonderment, curiosity, and unstructured exploration of childhood. Returning again and again to the deepest part of ourselves and then working from that place out.

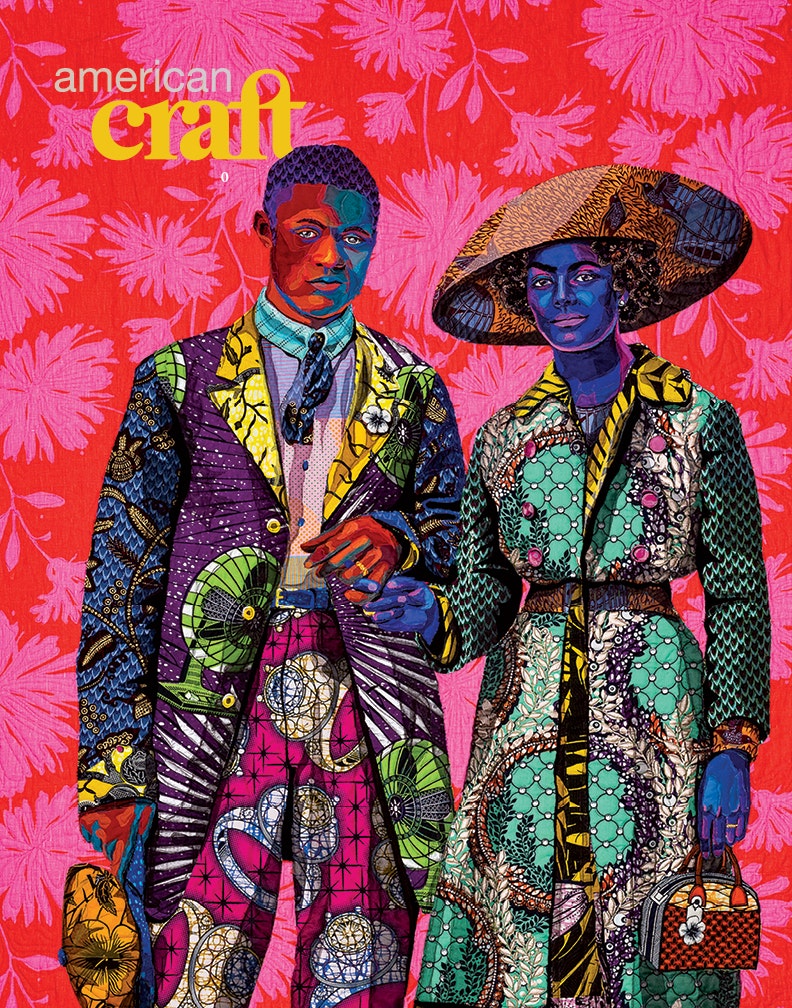

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.