Resurrecting a Legacy

Resurrecting a Legacy

I first heard of Emil Milan at the 2012 American Craft Council show in Baltimore when I met Norm Sartorius and asked him to be my spoon carving mentor. I had been working as an administrator at Penn State and longing for a creative outlet. Attracted to woodworking, I had found Sartorius’ work online and was amazed at his boundless creativity. I came to Baltimore that day to ask a master to take me on as a student. But I found myself embarking on two journeys: One was learning spoon carving; the other was learning about the life and work of Emil Milan.

Born in 1922, Milan was a prominent midcentury designer and artist in wood. By all accounts, he was a gentle, generous, and gregarious man with a big personality and a sense of humor to match. As a woodworker, he sought to design and produce what he called “functional sculpture,” particularly bowls, servers, and trays that are at once ergonomic and beautiful. His elegant creations were in early exhibitions of the American Craft Council, including “Designer Craftsmen USA 1953,” the first traveling exhibition of American fine craft. The show’s lineup was a who’s who of contemporary craft, featuring luminaries such as Bob Stocksdale, Peter Voulkos, and Kay Sekimachi; its success helped fuel the studio craft movement across the country.

While many of his peers became national figures, Milan slipped into relative obscurity after his death in 1985. One might wonder why; I suspect it was, in part, because of his move from his longtime home in northern New Jersey, near the New York art scene, to an old dairy farm in rural Pennsylvania. To a large extent, he traded renown for a simpler, more self-sufficient life selling his affordable, artful objects and teaching woodworking in his studio and at schools such as Peters Valley School of Craft.

I learned all of this while studying spoon carving under Sartorius, who had apprenticed with Phil Jurus, himself a Milan apprentice. Those relationships led me to see Milan – a man I was just learning about – as my ancestor in craft.

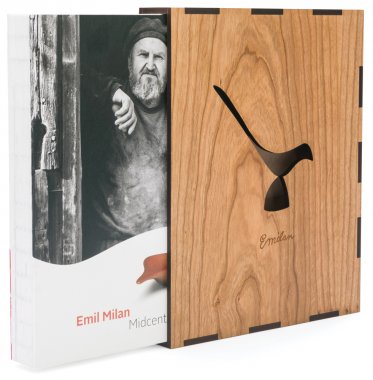

Since 2008, Sartorius, Jurus, and fellow woodworker Barry Gordon had been working to increase awareness and appreciation of Milan’s life and work. Impressed by their devotion to Milan’s legacy, I was compelled to join their project. Over the six years that followed, I dove into researching Milan and eventually wrote Emil Milan: Midcentury Master, published in May.

As I learned more about his life and work, I saw in him the rare flash of something special, like a sparkle of gold in a pan of sand and dirt: the rich vein of authenticity. His story is an American tale. It winds through the 20th century, entwined with the rise of fine craft in the US and the development of the ACC. The picture that emerged was that of a man I grew to revere, even though I never knew him.

I absorbed his reverence for wood and adopted his sensitivities to the curves of nature. I assimilated some of his ability to balance form and function. I also aimed higher when I learned how he encouraged students to develop their own designs. My expectations and standards for my own work rose after I read one of his handouts for students: “Make sure to do the best that you can do, not just what you can get away with because others do not know what is good.” I began to think that doing less than my best work was simply unethical.

I also got to know a remarkable human being. Like those who are hooked on genealogy, I found both a passion for researching Milan and a deep satisfaction in learning more about him – for I was also learning about my own artistic journey. What more can we ask of any labor of love, I wonder, than for it reveal us to ourselves?