Origin Stories

Origin Stories

While hiking in the desert earlier this year, I found a perfect little cube of charcoal in the middle of my path. It stood out against the sandy ground, a deep rich black in stark contrast to the golden-brown surrounding it. I picked it up and examined its shape and texture, waffling about whether I should carry it with me in my palm or put it in one of my pockets, potentially crushing it and having charcoal dust settle into the seams.

This piece of charcoal—probably no bigger than a small cube of cheese—took me back for a moment to 10 years earlier, when a friend was making charcoal in a fire pit, demonstrating the process to a group of artists. The results were beautiful: chunks of inky black pigment with surface luster like that of lead pencils. Everyone was awestruck and excited. Despite our prior “understanding” of what charcoal was, making it intentionally from the wood that surrounded us on this site—wood from the hundreds of acres of hardwood forest that embraced the property—was a revelation.

Finding this small piece in my path, as opposed to intentionally seeking it out, made me want to disperse it in place. As my partner and I turned back from our walk, I drew a simple symbol to represent the day on the generous, flat face of one of the boulders that marked the midpoint of our hike. The drawing was exactly the size of the piece of charcoal, in the sense that it was finished when the piece was exhausted down to its last crumb of pigment.

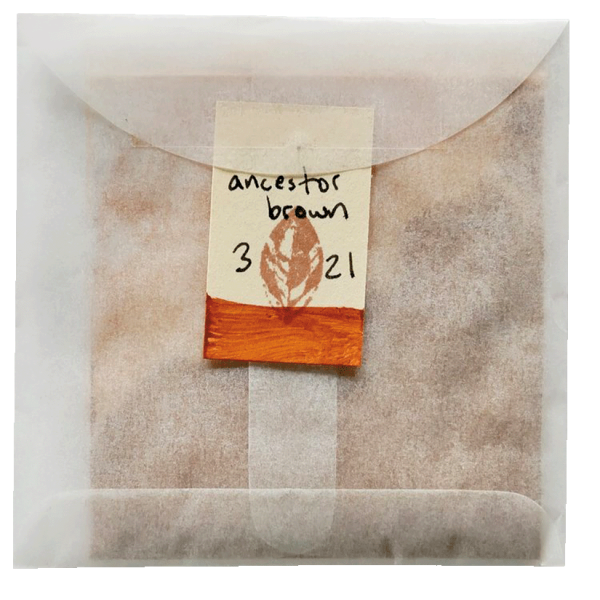

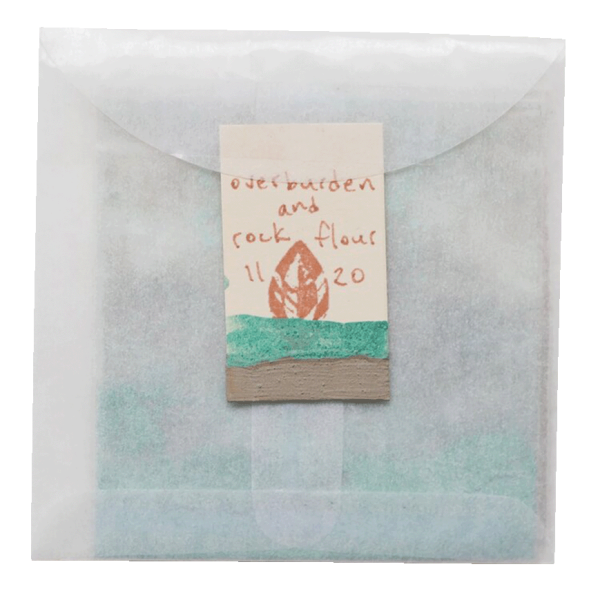

Balls of foraged pigment and colored leaves in Tilke Elkins’s Ground Bright Leaves installation. Each pigment is part of the Ground Bright subscription. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

That experience, unexpected as it was—not quite foraging but akin to it—resonated with me as a simple ritual. I experienced a heightened sense of presence throughout this activity and an awareness of the place I was visiting—the geological, atmospheric, emotional, and visual aspects, and the sense of time embedded in all of it. Because of this, the process of making a mark with the materials of the day was a surprisingly earnest one. We left our simple symbol, one we came up with on the spot, to the quick work of the weather. It was left behind less as a remark to others that we were there, and more as a punctuation in time. Stopping to notice and feel a place and our temporary contact with it felt briefly and truly intimate.

Finding and collecting materials from the land in a respectful way is an act of noticing and listening to the world; the presentness and attention in the process inspires a slowing down and forges a deeper relationship to place. As I learn more about artists who forage and process the materials they work with, it is apparent that such acts create both a sense of place-as-being and strong connections to the histories embedded there. To work with materials in this way is to more deeply connect to and think using place—both the wild and human-altered. These artists not only use found or foraged materials, which lots of makers do, but also embrace the histories and stories tied to the materials and include them as part of their process and finished works. And that has impact.

Transforming Relationships

Other artists and work have also helped me see the relationships between foraging and thinking, between place, stories, and understanding.

British textile artist Alice Fox works to “develop a deep connection with place and material” and live with a small environmental footprint. In West Yorkshire, she manages her own allotment—a small area of land leased from a private landlord or a local government authority—making her art from what grows wild and what she cultivates there. Part of her work is simply processing materials. Then she stitches together, delicately weaves, or “mends” them into textiles. With the dandelions that populate her allotment, for example, she dries the stems and makes cordage that she weaves. “I’m trying to use things that are classed as weeds just as much as I might use the things I plant,” Fox writes in her book Wild Textiles: Grown, Foraged, Found. “My garden and allotment are a slightly riotous mix of cultivated plants, sown or planted specifically, and self-seeded plants, which I can choose whether to leave in place or ‘weed’ out. This is an ongoing conversation between gardener and plants.”

Fox gathers and dries various plant fibers in her allotment shed in West Yorkshire, England, storing them for later use. Photo by Carolyn Mendelsohn.

Long dandelion stems, which Fox also uses for cordage. Photo by Alice Fox.

Downing, pictured here during her residential fellowship at the Lunder Institute for American Art in Waterville, Maine, in 2022, uses foraged clay in her ceramic works, including vessels and wall hangings. Photo by Ben Wheeler.

E. Saffronia Downing forages clay in her former backyard in Chicago in 2019. Photo courtesy of E. Saffronia Downing.

Founder of the Toronto Ink Company (and also a contributor to Ground Bright), Canadian Jason Logan has an ink-making practice rooted in experimentation and creating with whatever can be found. But unlike found-object sculpture or ad hoc arts, Logan is not assembling the things he finds. Instead he transmutes them. He releases color from these materials, making a new object through what appears to be alchemy. That new object, ink, tells the story of the materials it was made from, about the place those materials came from. Those stories are carried forward into the pictures or words the ink will make. “I think of your work as a map,” says author Michael Ondaatje to Logan in their conversation that concludes Logan’s book Make Ink: A Forager’s Guide to Natural Inkmaking.

For Liz McCarthy and E. Saffronia Downing, clay and place are nearly inseparable. Both artists value the intentionality of foraging clay from a site and bringing the histories of that place into the concept of their work.

Downing, an emerging artist based in Maine, centered her 2020 graduate thesis show at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago around her work using clay foraged from Chicago’s historic clay pits, relics of the city’s brickmaking past. Combining waste glaze, foraged clay, and other found materials—also referred to as “discarded” or “detritus” in her materials list—she refers to her use of “wild clay” as a means to map material histories. Recent work, such as her exhibition Field Dug Over at Bad Water Gallery in Knoxville, Tennessee, creates something akin to a topographic map of the relationship between the built environment and its natural foundation, with a tight section of clay slabs, both glazed and unglazed, laid out atop a dirt floor.

Chicago-based McCarthy, who intermittently uses foraged clay in their work, frequently sculpts clay bodies, either identifiable as human figures or shaped in ways that suggest fleshy forms. For years they have produced an ongoing series of whistles, both singular and “built for two,” that bring the living body into connection with the clay one. In their classes, they frequently teach about clay foraging and the development of a reciprocal relationship with the landscape, both of which can be integral to the meaning embedded in an artwork and its process.

The base of McCarthy’s 2022 untitled painting, 4 x 5 ft., is pigmented clay they gathered in Chicago; the shapes applied to its surface are made from Chicago clay fired at various temperatures. Photo courtesy of Liz McCarthy.

Expanding Empathy

The commonality I found across artists foraging materials was a commitment to mindful, compassionate relatedness to land, to place, and to the environment. That kind of relatedness can be not only healing but transformative. My takeaway is that foraging for materials—working and thinking with them thoughtfully and specifically, and considering their origins—is a kind of healing, transformative dialogue with the planet: the land, the human and nonhuman, the wild.

“Perhaps counterintuitively,” Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and her collaborators write in the introduction to Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, “slowing down to listen to the world—empirically and imaginatively at the same time—seems our only hope in a moment of crisis and urgency.” Could this intimate conversation that artists are having with place have the power to bring maker and observer closer to the earth that supports all our lives, including nonhuman ones? As Ursula K. Le Guin writes in the same book: “Science describes accurately from outside; poetry describes accurately from inside. . . . We need the languages of both science and poetry to save us from merely stockpiling endless ‘information’ that fails to inform our ignorance or our responsibility.”

This article was made possible with support from the Windgate Charitable Foundation.

Want to learn more about the craft artists inspiring contemporary craft? Become a member today!

Become a member of ACC today and receive a season subscription to the award-winning American Craft magazine along with several other exciting benefits!