A New Rhythm

A New Rhythm

Looking at Wade Folger MacDonald’s refined, sophisticated work, you might not guess that he hit an artistic brick wall a few years ago. He was in graduate school at Michigan State University, pursuing his dream of opening a pottery studio in the mold of legends Otto and Gertrud Natzler.

But his work just wasn’t cutting it. “My first critique with pots was just horrendous,” he admits. He wasn’t churning out pieces fast enough to keep up with assignments. Plus he was preoccupied: In his mid-30s, he was separating from the wife he’d met many years before. He started to question his choices, including his plan to devote his career to functional wares. “I realized that I couldn’t express myself honestly through pottery anymore,” he says. “I had to switch gears.”

You might think the realization came as a shock, but for MacDonald, it was pure relief. “I felt like I had much more freedom to do what I want and explore other things,” he says. After surrendering his largely pragmatic goal to run a pottery business, which he had hoped would offset his college debt, he began to find his artistic voice. “As soon as I let go of that, I think I started to really grow.”

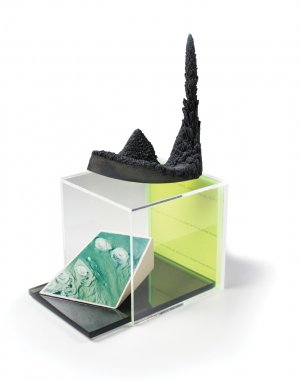

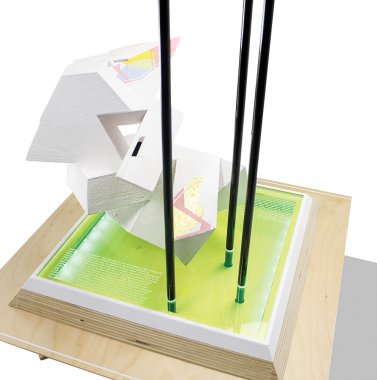

MacDonald, 41, now teaches ceramics at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, about an hour from Birmingham, where he lives with his partner, painter and instructor Anne Herbert. He builds strikingly angular sculptures that resemble avant-garde architectural models. Often encased in colorful plexiglass vitrines, they are at once modern, flashy, introspective, and challenging.

MacDonald was born in Nashville and raised in Kalamazoo, Michigan; his parents had been opera singers, and he grew up immersed in music. He spent his free time playing classical bass and drawing before earning an art education degree at Western Michigan University. In his third year, he took a wheel-throwing course and fell in love with the feel of wet clay.

A number of labels could fit his work – fine art, architecture, furniture design – but MacDonald proudly calls himself a ceramist. You wouldn’t know that at first, approaching one of his deftly constructed counter-weighted pedestals. Step closer, however, and a clay object is always somewhere near the heart of the work; it isn’t always front and center, but it’s a centerpiece nonetheless. And the ceramics world has taken notice: He won a 2018 Emerging Artist award from the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts, which recognizes exceptional work early in a career.

In his geometric works, MacDonald grapples with sweeping ideas: loss, human connection, the limitations of the mind, and the artistic struggle to fully capture an experience or truth. He calls on deconstructivist architecture (of which Frank Gehry is the best-known disciple), early 20th-century design, and Cuban American artist Jorge Pardo, whose work spans sculpture, installation, high-end lighting, and architecture. The same contemplative bent that hindered his production career is now an asset. His complex works are designed to be taken in slowly. “You need to spend time with the pieces, because they’re complicated,” he says. “You have to be able to experience the display and all of the ways that the ceramic pieces are situated within the vitrines. If you glance and you move on, then you’re not really experiencing the work.” His hope, he says, “is that people slow down enough to really look at the details.”

MacDonald wants you not only to slow down, but also to crouch, stand on your tiptoes, peer sideways, even bump your knees against the pedestals. Give it some time, and the many carefully designed elements begin to emerge: jutting angles, pastel glaze marks on ceramic centerpieces that almost blend into the shadow cast over them, text etched in colored plexiglass plates, the slits he sometimes cuts into the top of his vitrines, the glow of lights encased within.

“It’s my way of manipulating the viewer,” he says. The colors of the plexiglass play a similar role. “It’s like looking through rose-colored glasses. You look at the world a certain way. I’m forcing the viewer to look through this color filter.”

MacDonald starts each sculpture by first thinking about how to display it. Using a 3D-rendering program, he designs the pedestals and vitrines that contain his ideas, both literally and figuratively. Only after these pieces are built does he begin to work with clay. He appreciates the limitations the vitrine presents, as well as how it elevates the ceramic elements. “It begins to talk about the space around the object and not just the object, and it gives this reverence to the object, a preciousness that you can’t get without that protective covering.”

Although he now dedicates himself to sculpture, MacDonald continues to produce delicate, decorative pots on commission as well as build furniture. But the big questions he wrestles with remain.

“I think language can only do so much, and visual art is still – you’re limited, in a way,” he says. “And so how do you do it? How are you able to reflect what you truly want to talk about?”