Intentions and Impact

Intentions and Impact

The south side of Chicago is a paradox – neglected, yet the focus of intense nationwide attention. It’s architecturally stunning, yet distressed by years of disinvestment. Outsiders peer in and make judgments, with little to no connection to the area’s rich history, complex present, and diverse mix of residents.

Responding to the crises that plague the South Side – high unemployment, urban blight, segregation – is a network of organizations masterminded by artist and University of Chicago professor Theaster Gates. Intended to build stronger communities through cultural programming, the separate entities are sometimes known as the Constellation. The network includes two university programs: Place Lab (“a catalyst for mindful urban transformation and creative redevelopment,” according to the website) and Space Fund (a charitable land trust developing spaces for artists, community organizations, and entrepreneurs).

The Rebuild Foundation lies close to the center of the network. Founded in 2010, the independent nonprofit presents programs, events, and workshops specifically designed to cultivate and celebrate black people and the black experience through the arts as well as to help redevelop the South Side through site-specific cultural institutions such as archives, film houses, building renovation, and job training. Its work is part of a larger trend of artists moving toward social practice – performative, site-specific, participatory – that highlights problems and seeks to offer solutions through art.

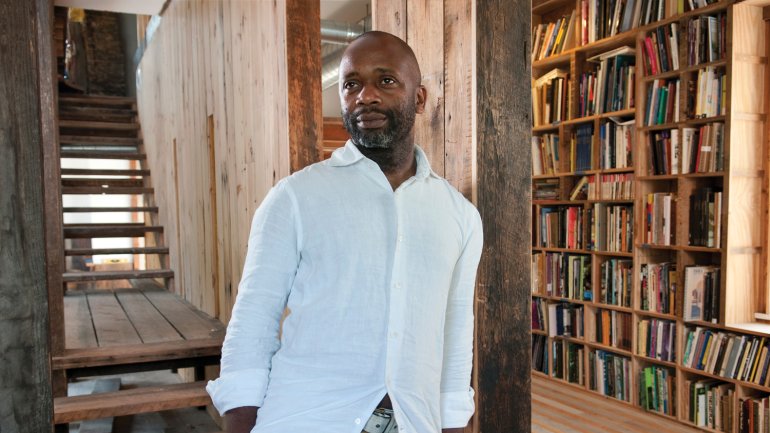

At the heart of this work is Gates, whose persona has two distinct yet linked sides: property developer and artist. In both roles, he’s ambitious. (As he told the Chicago Tribune in 2015, “I believe that all the work I do is art, and artists should make art in the biggest ways possible.”) Ultimately, his story highlights the challenges of combining art and real estate development and the unintended consequences that can befall social-practice artists, no matter how well-intentioned.

Reclaiming History

Trained as a potter, Gates primarily makes sculpture and installations using found materials – sometimes detritus from abandoned buildings – that are physical relics of various histories. His 2010 installation at the Whitney Biennial used wood from a derelict Wrigley Gum factory to build a large-scale, modular performance and meeting space in the museum’s sculpture garden. Some of his more recent work includes “paintings” made with gymnasium flooring from Chicago’s shuttered schools.

His reclaimed-material works allude to the black histories and the cultural richness that saturate architecture, art, and community development on the South Side, while referencing the extreme neglect the area has suffered. It is at this intersection where Gates begins his secondary practice in “ethical redevelopment” (a term used by Place Lab), purchasing real estate on Chicago’s South Side that he transforms into arts and cultural spaces. He’s been doing it for almost a decade.

Aiming to Do Good

The Rebuild Foundation plays a major role in Gates’ revitalization initiatives. The organization is housed in his best-known “ethical redevelopment” project, the Stony Island Arts Bank, a long-abandoned building Gates bought from the city for $1 in 2013, with a plan to turn it into a hub for community and culture. Sitting at the crossroads of two underserved South Side neighborhoods, Woodlawn and Greater Grand Crossing, the bank is a striking space for programs and archives of black cultural objects, music, history, and ephemera.

It’s also a reminder of a once-thriving community. Originally a savings and loan, it sat vacant from the 1980s until Gates reopened it as an arts center in 2015. A hefty renovation preserved or restored ornate architectural details. Gates even repurposed marble slabs into works of art he called “bank bonds” and sold to patrons, using the money to help fund the bank’s rehabilitation. In the rehabbed building, flourishes of unfinished ceiling and paint-stripped walls remind visitors of its recent past, amid the refurbished expanse of gathering and exhibition spaces, offices, and a library.

There, the Rebuild Foundation hosts myriad arts programs that put people to work, physically and intellectually. The free events, exhibitions, and cultural amenities are informed by values described in their mission: “Black people matter, black spaces matter, and black things matter.” One long-standing project, the Black Cinema House, screens films relevant to black history and experience, from narratives to documentaries to experimental films, as well as “home movies” by amateur videographers and filmmakers, which Gates describes as “smart ways to capture and offer intimate glimpses into the everyday black experience.” BCH encourages citizens to make their own movies by providing cameras and equipment training, as well as training on editing software for people who want to shoot footage on a camera phone.

One of Rebuild’s recent initiatives, Dorchester Industries, was inspired by Gates’ desire to engage neighborhood residents in carpentry and construction tasks in his development projects. “The workforce program exposes the participants to all aspects of the business of the arts,” says program manager Sam Darrigrand. “There are real jobs that involve installing neon art, crating artworks, etc. Theaster’s idea is that the work is there and needs to be done; why not turn that work into pedagogical moments and employment opportunities for the neighborhood?” he says.

A typical day for trainees ranges from art handling to demolition to construction. Painting, warehouse organization, and community garden work are also common duties. Participants can leverage their new skills by earning credentials that help them find other jobs.

Under Fire

As promising as these programs sound, they have recently come under sharp attack. In April, an anonymous user accessed Rebuild’s Twitter account to allege unfair employment practices and unequal treatment of black employees, citing a white managerial staff, as well as little chance for black staff members to advance in the organization.

The user also demanded that a human resources professional be hired and called for Gates and Amy Schachman to resign as executive director and director of programs and development, respectively. (Schachman left the organization shortly after the Twitter incident. She could not be reached for comment.)

As reported in the May 23, 2017, issue of the South Side Weekly, these demands and allegations were articulated two months before the hack by the Black Arts and Artisans Labor Coalition, led by former Rebuild employee Darren Wallace. The group also mentioned a 2014 article that took issue with Gates’ “ethical redevelopment” approach. In “Art & Gentrification,” in the British magazine Art Monthly, writer Larne Gogarty scrutinized the nature of Gates’ social practice work. “Though Gates has largely eluded the usual ethics-versus-aesthetics debate due to his success in the mainstream art world,” Gogarty charged, “his practice readily invites criticism that the ‘usefulness’ of his Rebuild Foundation is based on compliance with a system that perpetuates the social issues it attempts to improve.” In other words, the redevelopment model Gates follows – to buy and fix up rundown properties – also spurs rapid gentrification and displacement of low-income people of color.

The Rebuild Foundation’s Board of Directors issued a response reaffirming their core values and rejecting the hacker’s claims. “These demands express misconceptions about the work that we do,” it reads. But the question remains: Do these projects actually increase access to the arts – or just gentrify the area, pricing out original residents?

As of press time, Rebuild had issued no cumulative report on the impact of the Constellation’s programming on the community it serves, nor would the interim staff at Rebuild comment on it. Operations manager Sheree Goertzen says that they are working on a report, although it is an internal project, not led by a neutral third party. Gates could not be reached for comment on this issue.

Learning to Fail

Questions about impact and concerns about gentrification aren’t new, and Gates isn’t the only social-practice artist subject to those critiques. Another thorny issue is the notion of failure. J. Gibran Villalobos is an emerging voice in Chicago’s arts programming community; he has worked with the City of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and the Chicago Architecture Biennial to create free, accessible programming throughout the city. His experience providing cultural programming to underserved communities has taught him that learning takes place on a steep curve.

“Arts programming is often about experimentation – throwing an idea on the table to see if it sticks. But there has to be space for failure,” he says. When they fail, arts administrators can see that there is no single or simple way to make effective programming. “Each community is different – one program that works in one community will not necessarily have the same results or impact in another,” he says.

The implication: Programming aimed at increasing access to the arts or regenerating a community is inherently risky; success in not guaranteed.

Opening Up

Perhaps it’s exactly that acceptance of vulnerability the Rebuild Foundation lacks – demonstrated by a lack of transparency in how the organization measures the success of its programs while serving some of the most vulnerable populations in Chicago.

Yet from his point of view as craftsperson, artist, and the engineer of a redevelopment machine, Theaster Gates is opening doors for the arts to have greater social impact. Rebuild’s programs are venues to discuss complex ideas and conflicts, through which, he says, “we’re creating sympathy and empathy and dialogue, which has allowed us to create a public that is super-generous and sensitive.”

Gates has been a critics’ darling for some time, profiled in glowing terms by the New York Times and the New Yorker, among others. But with greater ambition for public impact comes greater need for integrity, transparency, reporting, and learning. As it stands now, Rebuild’s inner workings are facing intense scrutiny. What Gates and his staff do next will be instructive for all artists and organizations with a desire to do good.