The Fashion Factor

The Fashion Factor

Bishop wears Waistcoat of Earthly Delights, 2021. In mid-19th-century menswear, only waistcoats still sported such ornate floral motifs. Photo by LOAM.

Fashion is also a meeting of the personal and the social/political. It gives a larger structure to the visual language of dress, which individuals use every day to communicate their sense of themselves and their place in the world. Even people who aren’t interested in fashion as such contribute to the fashion landscape of their time. The shape and fit of clothes, the material, color, pattern, method of production, advertisement, and sale—these all affect what is being said by our clothes.

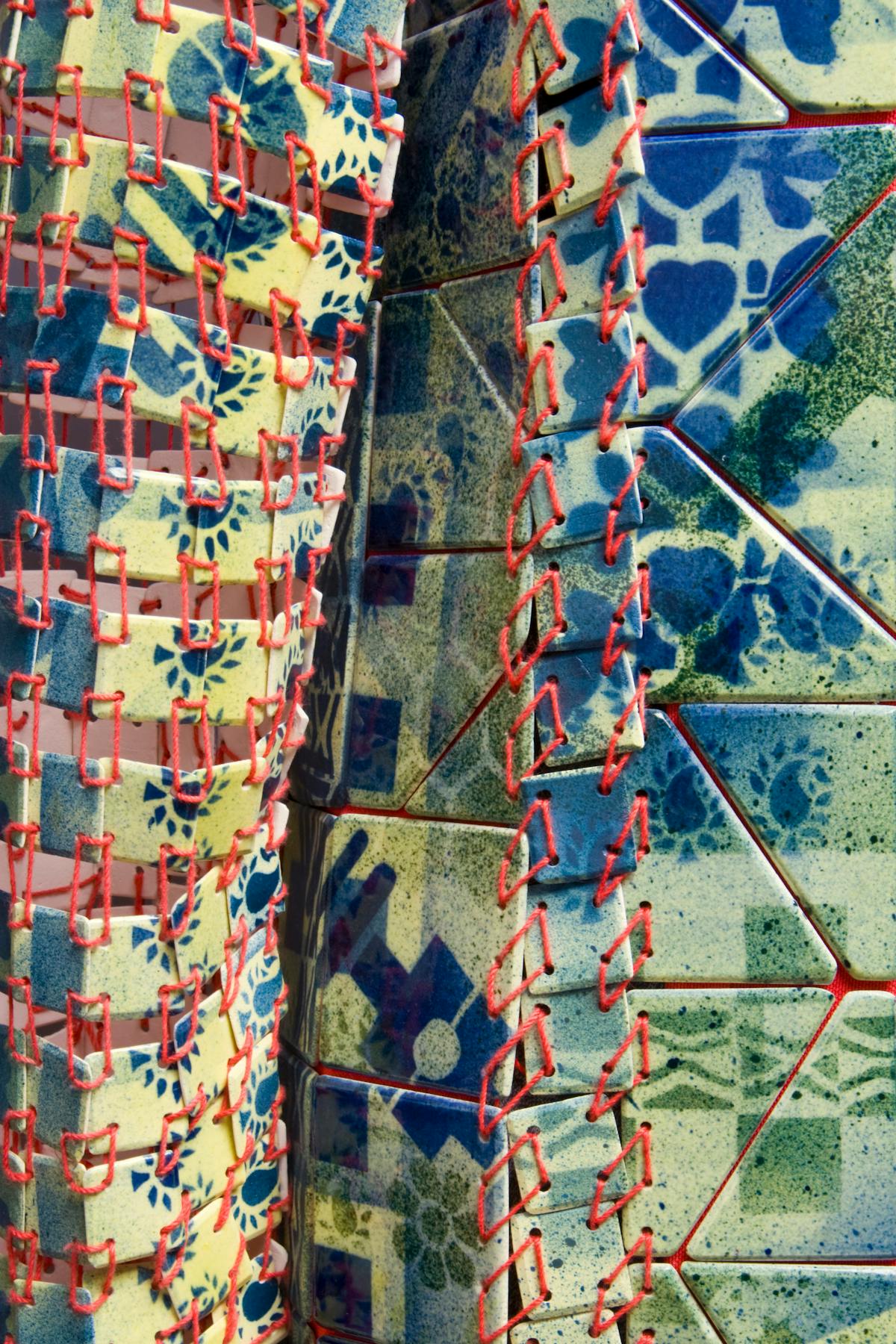

TOP: Bishop working on the belt of his chaps, a stitched-together mosaic of ceramic tiles plus PE braid, canvas, leather, and brass. The blue ceramic hat at upper left completes the ensemble Eternal Cowboy. Photo by LOAM. BOTTOM: A closeup of the chaps. Photo by Myles Pettengill.

How might a craft artist articulate this interplay between social-historical patterns and personal expression? I can speak for myself: in my own work I reference the history of fashion, along with the history of ceramics and my own lived experience, to create something akin to wearable portraits. I make sculptural garments from ceramic and fiber materials, often by lacing together hundreds of small tiles.

Ceramic represents history to me, something hard and long-lasting, heavy but fragile. Textile represents the individual—flexible, soft, and personal. Merging the materials, I am seeking to merge the personal with the historical, to locate myself and my individual narrative within the larger story of human culture. I use the vocabulary of clothing to construct this narrative.

In my Fragile Masculinity series, for example, I use ceramic cowboy hats with colorful floral decoration to explore the paradoxes of archetypal American manliness. To study the history of floral motifs in menswear, in fact, is to reveal broad historical shifts in how fashion conveys identity. In the case of florals, those shifts are strongly tied to gender.

This coat, 2011, was the first ceramic garment Bishop made. Photos by Jim Walker.

In Europe, from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, floral garments were worn by both men and women. Colorful dyes, imported brocades, and laborious embroidery were expensive, so bright flower-patterned clothing demonstrated wealth and prestige. But during the 18th century, florals began fading as men’s clothing modernized. Surface decoration and color were increasingly perceived as frivolous, and thus relegated to the female wardrobe. Flowery clothing became part of a stereotypical ideal of delicate, ornamental femininity.

But as American western wear developed, flowers kept a niche place in male-gendered clothing, influenced by Indigenous beadwork as well as European embroidery. Perhaps an “exotic” perception of the frontier allowed exceptions to normal taste. “Wild West” outfits often featured flowers, especially costumes romanticized for mass audiences in shows and movies. Flowery shirts, boots, and leatherwork became popular, reaching a peak in the flamboyant Nudie suits of Hollywood actors and musicians from the 1940s to the 1980s. Today, florals have regained wider acceptance in fashion as society’s view of gender norms in clothing becomes more inclusive.

Another element of fashion that informs my artwork is the formalization of specific functions. While “fashionable” garments are often thought of in the context of red-carpet galas, in a broader sense fashion includes specialized and very functional garments, from sportswear to work wear, which often influence high fashion.

A Swimsuit to Wear While Looking for Hellbenders, 2020, white porcelain and black stoneware. Mannequin photo by LOAM. Outdoor photo by Myles Pettengill.

The idea of making garments for specific activities is relatable to the craft world, where artists think about function in similar ways. In ceramics, if I make a cup, I’m thinking about the intended beverage, the cup’s most appropriate size and shape, and whether it has a handle. Most garments, including the most fashionable, began with similar considerations of function, even if time has divorced them from those roots. Tailcoats, now worn only for the most formal white-tie events, were originally made for easy horseback riding in the 18th century. Even jeans, which are ubiquitous and often high-end fashion today, started out as sturdy pants for mining. Just as in craft, fashion exists under productive tension between utilitarian function and formal aesthetics.

I believe in the craft world we can draw from the language and history of fashion, not only as visual inspiration, but as a conceptual framework to convey meaning. It can be tempting to dismiss fashion, and thereby underestimate its importance. Fashion should be understood not just as an industry capitalizing on vanity, but as a key part of how humans construct group and personal identity, as well as a full-fledged visual art. While the contemporary world of fashion operates very differently from that of craft, there is so much common ground in construction techniques, material understanding, function, and history.

Clothes are crafted objects that virtually become part of the body; they are loaded with symbolic implications, and this in turn gives them enormous power and makes them worthy of serious thought. Often derided as being superficial and frivolous, fashion is a reflection of ourselves and our time, always flawed but always beautiful.

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.