Circle of Knowledge

Circle of Knowledge

Left to right: April Stone, Maggie Thompson, and Pat Kruse at Thompson’s weaving workshop for Craft Labs in August 2020. Photo by Tamara Aupaumut.

Tamara Aupaumut is a multidisciplinary artist and independent curator descending from the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican, Oneida, and Brothertown nations. She lives and works on traditional Dakhóta land, Mni Sota Makoce, also known as Minneapolis, Minnesota. Photo courtesy of Tamara Aupaumut.

My first introduction to traditional Native arts was in the 1980s. Gordon Campbell was a social worker in Indian Education at my elementary school in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and he introduced me to beadwork. Due to cultural assimilation, traditional practices had been lost in my family for generations, so this was a momentous point in reclaiming my heritage as a Native American. Gordon introduced me to a community that shares my values and is deeply rooted in nurturing one another, one that has since given me strength, guided me, and nourished me unconditionally. His impact on me is something I reflect upon every time I pick up a needle and thread and start beading. Most important, he taught me the true meaning of relative. And because of him, community mentorship has always been a way for me to connect to my cultural identity.

I see mentorship as being about relationships and restoration, lessons, and medicine. Because of this, I knew it was important to explore mentorship as part of my residency at the American Craft Council. As the curator-in-residence, I helped launch Craft Labs, a new program with a mission to give diverse craft communities more visibility, to support and encourage diverse artists, and to preserve and advance knowledge. As I began to plan an exhibition with these criteria in mind, inspiration came from conversations about my community and how we learn art forms in our culture, how mentorship nourishes us, and how that gift is passed down through generations.

I decided to produce a series of workshops as part of the exhibition and invited three Ojibwe artists whose work I admire to participate as both teachers and students: April Stone (Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), a traditional ash basketmaker from northern Wisconsin; Pat Kruse (Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), a traditional birchbark artist exploring a contemporary narrative, who lives on the Mille Lacs Indian Reservation in Minnesota; and Maggie Thompson (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), a contemporary artist and textile designer who lives in Minneapolis.

Mentoring Each Other

After some postponements due to the global pandemic, workshops by these artists-in-residence were held in my Minneapolis backyard last summer. While we had originally intended to invite other community members to the workshops to share in the learning, we wanted everyone to stay safe from the coronavirus, so only the artists and I participated. We spent three straight days of intensive learning, sharing, and making; each day an artist instructed our small group on their craft.

Birchbark hats made by April Stone (center) and Maggie Thompson (right) as part of Pat Kruse's workshop. On the left is a hat Kruse made later using techniques from the other two artists' workshops. Photo by Jaida Grey Eagle.

Birchbark Hats. Pat Kruse has been working with birchbark for over 30 years. He creates traditional birchbark baskets, some adorned with traditional Ojibwe quillwork. He also blurs the line between traditional and contemporary art by expanding on traditional materials and functional pieces to create modern, large-scale, two-dimensional mosaic work. Pat learned his art in part through community workshops, but mostly from his mother, Clara. For him, sharing cultural teachings and telling stories through his art is a way to celebrate his Ojibwe heritage and to honor the ancestors that passed down these traditional ways. “Our art is our podium,” Pat says. “It’s our livelihood, our future for our children. The art speaks for your time, for what you’re doing while you’re here.”

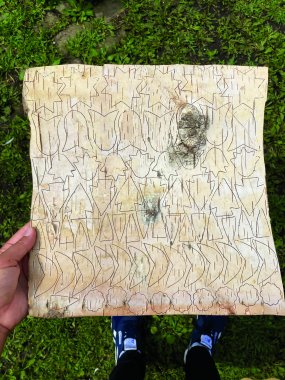

In Pat’s workshop we learned how to make an Ojibwe baseball hat out of birchbark. He had discovered the hat in an old “culture keeping” book that belonged to a medicine man on the Grand Portage Reservation in northern Minnesota. The medicine man asked Pat to create a hat for him, and afterward Pat successfully created a pattern. He felt it was important to share his pattern with his fellow Ojibwe artists.

Pat, who harvests the birchbark himself, showed us multiple pieces of the bark with different textural qualities and colors that could be used. Then he gave us instructions. First, we cut the bark into shapes to form the hat and created traditional Ojibwe floral pieces out of bark to decorate the brim. Next, we made holes so the hat could be sewn together and completed using artificial sinew, rather than the traditional animal tendon. Because birchbark has medicinal qualities, it was healing for all of us to touch and work with something that had sustained our ancestors’ survival for so long.

“I have always wanted to learn how to make Pat’s birchbark hats, so it was definitely a dream-come-true kind of experience,” says Maggie. “Learning from Pat, I really liked thinking about all the layers that go into making something, which I hope to carry on in my own work.”

pat-kruse.com | @patkrusebirchbark

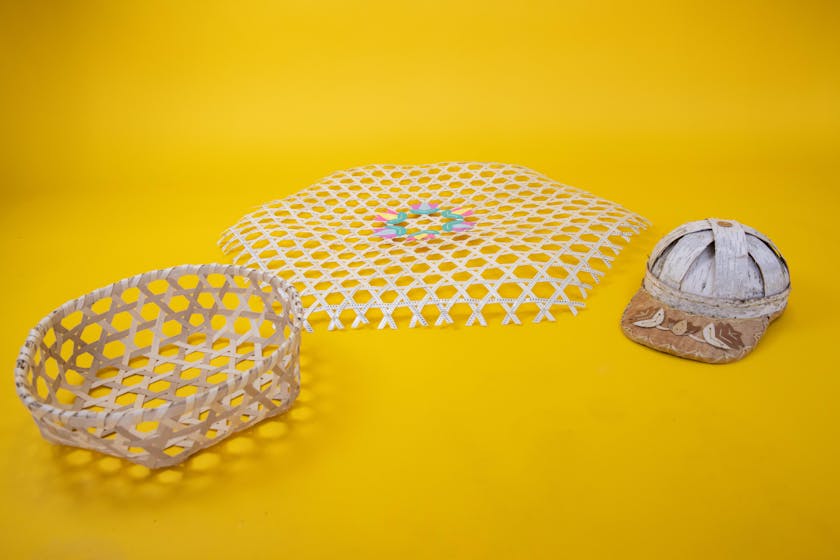

Maggie Thompson and Pat Kruse each made black ash baskets as part of April Stone's workshop (front). Stone in turn incorporated learnings from Thompson and Kruse's workshops into her response project (back). Photo by Jaida Grey Eagle.

Black Ash Baskets. April Stone is a self-taught black ash basketweaver who harvests the hardwood herself. She was once told by a student and First Language speaker that the word for black ash in Ojibwe is baapaagimaak. The root of the word relates to two other words: aagimaak, meaning ash, and bapakine, meaning grasshopper. April said it’s believed that bapa/baapa relates to the “beating of the grasshoppers’ legs and beating the wood to separate.”

In 1998, few Ojibwe on her reservation were making black ash baskets. That’s the year April, who hadn’t yet started making them, closely observed one basket and how it was used. She was unaware at the time of the intimate relationship that was being formed between her and the ancestral craft. At one point the basket needed repairing. That’s when the strength of this natural material captured her curiosity and launched her exploration of basketry. April could see traditional teachings showing themselves through all aspects of creating a basket. The lesson of healing revealed itself to April through the creation of her burial baskets. It also emerged in her students, with many accounts of how working with the material and their hands had empowered them and shifted their energy to carrying themselves more confidently with a renewed self-assuredness.

In her workshop, April taught us how to split wood and then soak it in preparation for weaving. “When learning from April, I really enjoyed learning about the preparation of the material,” says Maggie. Then she instructed us on how to create a basket in a hexagon weave. The pattern is complicated and challenging at first, but with her reassuring guidance we developed an understanding of it.

For Pat, who had never done any ash basketry work, nor weaving, the experience was challenging. “April’s teaching, and Maggie’s, gave me insight into how hard their work actually is. It gave me a perspective on how valuable that work is.”

At one point when I was working on my basket, I was overcome with emotion looking at my hands. In that moment I imagined that my hands were those of my grandmother, and her hands were again creating baskets.

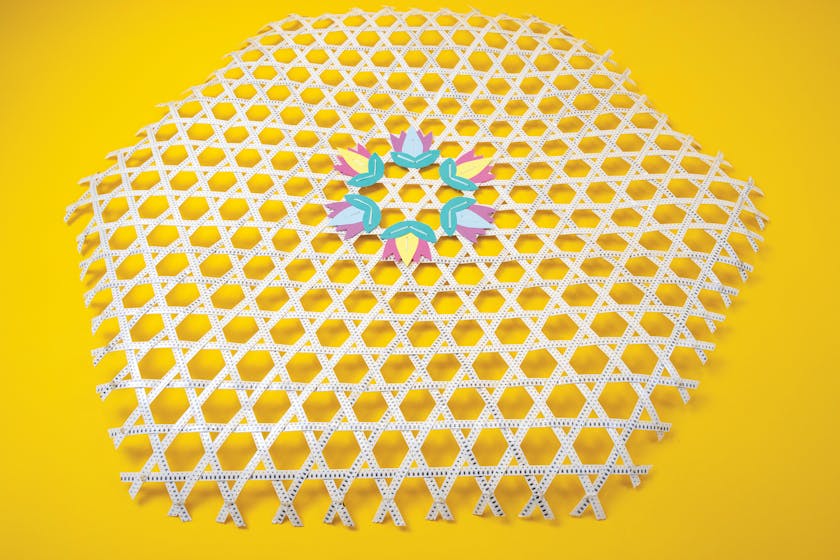

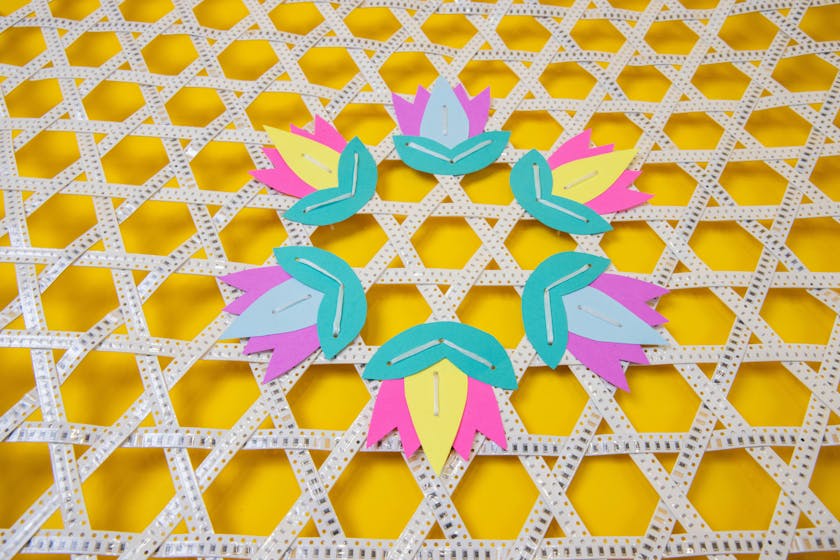

Weavings made by April Stone (left) and Pat Kruse (right) in a workshop led by Maggie Thompson. The wall hanging in the center is Thompson's synthesis of all three of the Craft Labs workshops. Photo by Jaida Grey Eagle.

Weaving. Maggie Thompson was first introduced to textile arts at the Waldorf School she attended as an adolescent, and she eventually graduated with a bachelor of fine arts in textiles from the Rhode Island School of Design. She derives inspiration from her Ojibwe heritage, exploring family history as well as themes and subject matter of the broader Native American experience. Maggie explores many types of materials and fibers in her work—some purchased, others reused—incorporating multimedia elements such as photographs, beer caps, and 3D-printed objects. She also runs Makwa Studio, a small but growing knitwear business.

While Maggie says that her work is not rooted in traditional materials, she works with sustainable materials, and in my eyes that is traditional. Her main focus is exploration, technique, and structure. She’s fascinated by taking something small and creating something large scale out of it. She discovered that the methodical and meditative process of weaving and knitting grounds her. Maggie uses art as a language to explore and convey her inner emotions and what’s most important to her: relationships. When Maggie’s not creating fine art and knitwear, working as a curator or an art instructor, or making the beautiful masks she donates for her Ribbon Mask Project, she is a role model in our community as a leader and arts organizer.

At the beginning of her workshop, Maggie introduced us to various yarns and nonconventional materials you can weave, such as horsehair, random fabrics, cording, and zip ties. Then the artists set up their looms and learned about warp and weft. Maggie worked with each artist individually to create a unique piece. Pat explored the medium by adding floral embroidery to his piece, and April created multiple blocks of color.

Pat says that the skills they learned in all workshops are important life skills. “With what Maggie taught, we can make a net. With what April taught, we can make a fish trap and go grab a fish. You can store food in my baskets. All those things are more than a basket, more than a weaving,” he says. “The more you learn about your culture, the stronger you get in your mind and spirit.”

makwastudio.com | @makwa_studio

Making Something New

During the workshops I could see an interconnectedness between the artists’ practices, and it reminded me that everything is related. Pat’s medium of birchbark related to April’s medium of ash. April’s technique of weaving with hardwood related to Maggie’s technique of weaving with yarn or softer materials. It conjured thoughts of evolution and how we as people hold on to tradition, and how tradition transforms over time, just as we do as people.

I also saw Craft Labs as an opportunity not just for community mentorship, but to further explore how art forms evolve. So, for their final exhibition piece, I invited all three of the artists to create a new piece that demonstrated knowledge gained from the workshops, and to incorporate materials or techniques they’d learned into their current practice.

Each artist created a final exhibition piece incorporating materials or techniques they learned about in the workshops. Pat Kruse incorporated weaving and black ash in his birchbark hat. Photos by Jaida Grey Eagle.

For his final piece, Pat created a hat that incorporated both weaving and black ash. Maggie, wanting to create a piece that was exploratory in its form and material, made a wall hanging. “I am constantly trying to push the boundaries of materials used in textiles so I ended up using some kind of film strip and cut cardstock paper for my final piece,” she says. “I used the strips to do a hex weave with and cut out the floral with the paper and stitched them onto the woven piece similar to the floral design work we did on the bill of our hats.”

Reflecting on her experience in the workshops, April Stone included birch in a black ash basket. Photos by Jaida Grey Eagle.

April says she spent a fair amount of time pondering what to make. “For my final project I desired to create something that was going to make people swoon and think and feel,” she says. “Time was ticking and nothing was coming. My thoughts and ideas ventured into the dream world, and I ended up having two very moving dreams: one dream revealed a birchbark cape with a cloth lining, while the other dream was about old baskets and new baskets and grief and release. Since I had no time to make what I saw in the dream, I felt that those two dreams had to do with other connections down the road.” In the end, she incorporated birch into a basket with simple curlicue work and a braided splint rim.

Maggie Thompson made a wall hanging with a hex weave, bringing together techniques from the three workshops. Photos by Jaida Grey Eagle.

Initially, we planned for an in-person exhibition for final pieces and workshop pieces, but with restrictions and health safety being prioritized, we are exhibiting Circle of Knowledge virtually for all to view.

I love seeing the diverse ways the artists interpreted and responded to my invitation in their final pieces. Seeing how the workshops will further the artists’ work and impact our community in the future is something I look forward to. My hope is that whatever they took from this time together, they pay it forward. I know they will. It’s up to each and every single one of us to be a good relative and grow and nourish a strong community; otherwise, culture, stories, language, and arts will be lost. Art in my community is so much more than making something. What we create embodies memories and preservation.

This online exhibition is dedicated in memory of Gordon Campbell. “Oneewe (thank you) to all the mentors—past, present, and future—your memory lives on in us!” says Tamara Aupaumut, who offers special thanks to Scott Pollock, Jenean Gilmer, Charlie Stately at Woodland Indian Crafts, and Wheelhouse Creative for their support. Craft Labs was funded by a grant from the Harlan Boss Foundation for the Arts.

Help Make Programs Like Craft Labs Possible as a Member

Joining the American Craft Council provides critical funding for a range of nonprofit programs that strengthen our community and connect people to craft, including our magazine, marketplaces, library, and more. Give your support today by joining at one of our membership levels and enjoy a subscription to American Craft and other benefits.