Birdman

Birdman

Tom Hill sees ballet in the low, soaring whoosh of a chicken and soulful intelligence in the eyes of the creatures that inspired the unfortunate epithet “birdbrain.” And although birds aren’t the only subjects of his sculptures, they are a recurrent theme across his two-decade body of work. “Birds are kind of miraculous,” says Hill. “They’re embedded in our folklore and our imagery . . . and we totally underestimate them.”

Born in Norfolk County, England, Hill spent a good part of his youth sketching – cranes on freezing December days in London’s Golders Hill Park and taxidermy models in natural history museums. The 45-year-old made the leap to three dimensions at the School of Art and Design at Middlesex University, graduating in 1994 with a degree in jewelry making, a choice he finds perplexing to this day. In any case, it did lead him to his primary medium.

“We had a silversmithing department, and this black wire was absolutely everywhere,” says Hill. “And one day I just sat down and started making this very simple bird.” It was the eureka moment, he says, that let him make the leap off the page. “Working with wire felt as free and loose as drawing, and allowed me to capture movement – which was critical, considering my subjects.”

His pieces really started to come alive after one of his tutors, enamelist Ros Conway, suggested that Hill check out Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential-motion photographs of animals. These became the catalyst for a number of multi-piece installations, where Hill uses wire to convey taking off, soaring, landing, and everything in between. One such grouping found a recent perch at a Lisbon restaurant, where a flock of ricebirds are arrayed “like scribbles on the wall” around the room – fixed, but not static. (Hill now uses his iPhone to shoot video and break down movement, something Muybridge could not have imagined.)

As he embarks on a piece, Hill often works from several drawings of different angles, some made long ago. When he moved from London to San Francisco in 1999 to be with his husband, Mike Holmes (founder and owner of Velvet da Vinci gallery), he brought all of his sketchbooks, which are stacked in piles and stashed in cubbies in the garden-level art studio of their Victorian; they emit little puffs of dust when pulled out of a pile. A neighbor’s fishpond attracts herons and snowy egrets to the backyard, satisfying Hill’s penchant for birds that are supported by improbably long legs.

However, whether working from life, a sketch, or his memory, Hill has no aspirations to be the Audubon of the sculpture world. Some of his creations are recognizable species; others are composites – “crowlike, pigeon-esque, owlish” – or entirely made up. “I’m never going for a perfect replica,” says Hill. “It’s more impressionistic. William Morris talks about how artists working from the natural world can’t convey the whole complexity of nature – and how the ‘debased’ art is the one where someone tries to render every feather.” Sometimes Hill takes liberties to reflect a deeper truth, such as sandpipers endowed with three legs, “which is what your eyes see when they’re running along the shore.”

Today, Hill tends to see birds everywhere, including in the sweet potatoes mounded up in shops before Thanksgiving. In his latest series, the sinuous forms create the bodies (which will later be replicated in more stable redwood) and handmade details – carved beaks, painted eyes, brass and steel feathers – fill in the rest. It’s Hill’s version of Mr. Potato Head and a nod to the craft projects he undertook as a child.

“Where the wire birds are almost non-corporeal, these are more solid and earthbound, with their own characters and personalities. And humor,” Hill adds quickly. “Sometimes craftspeople are so desperate to be taken seriously, we shy away from humor. It’s like the Oscars – when’s the last time a comedy won for Best Picture?” he asks, laughing. “I think that looking at animals makes it easier for us to laugh at ourselves,” he continues. “And humor is the only way we survive.”

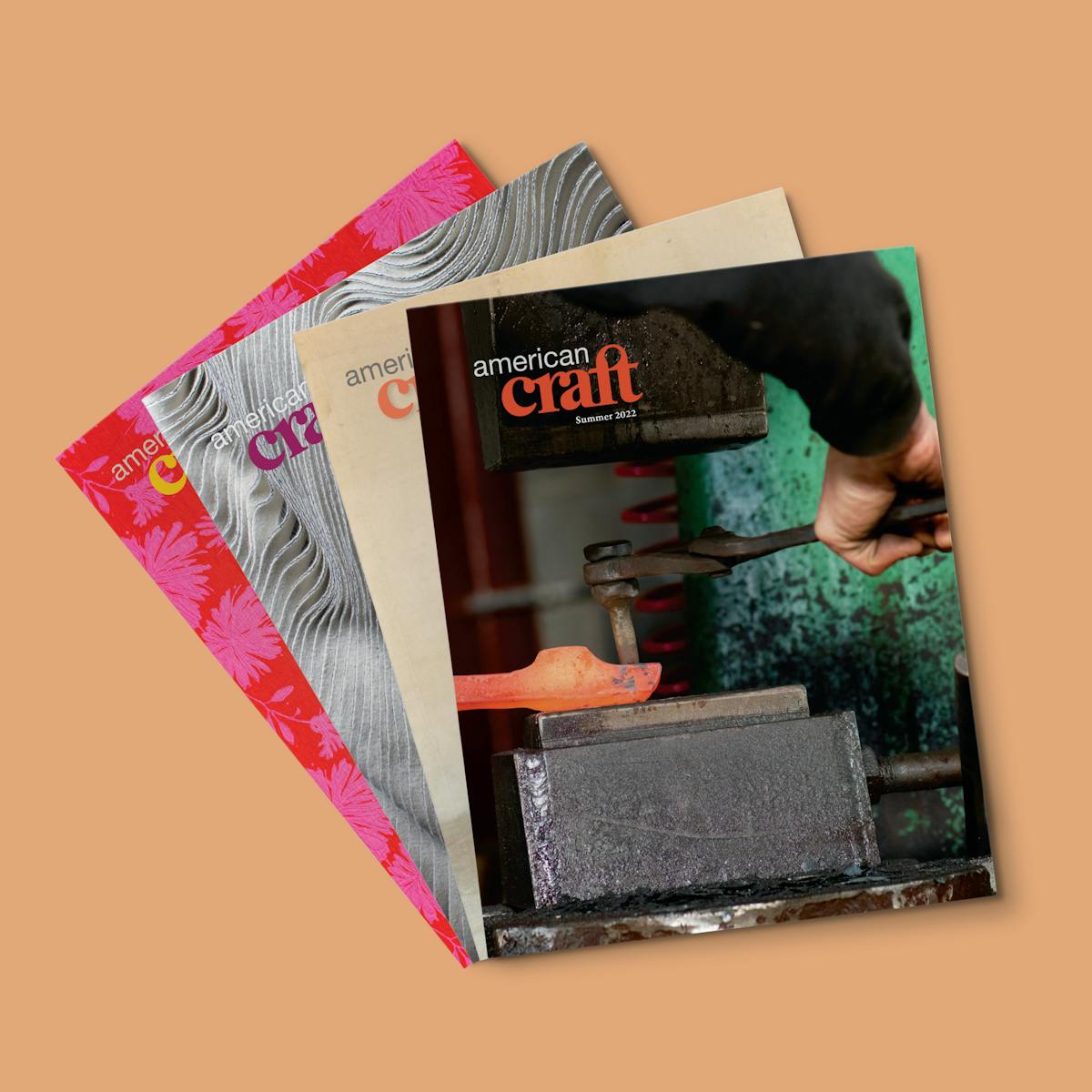

Discover More Inspiring Stories in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.