Making as Morality

Making as Morality

“The finest fruit of education is character; and the more complete and symmetrical, the more perfectly balanced the education, the choicer the fruit.” ~Calvin M. Woodward, The Manual Training School, 1887

More than a century ago, craft education in the United States wasn’t meant only to make you a better potter or a more marketable cabinetmaker; it was also meant to make you a better person. Education reformers in the 19th century argued for the instruction of both the hand and the mind as an improvement on the teaching model of rote memorization and recitation. But unlike an apprenticeship, which prepares someone for a craft or trade, training children in handwork was intended to promote “the healthy growth and vigor of all the faculties” and the “general robustness of life and character,” according to Calvin M. Woodward, who wrote a book advocating the movement in the late 19th century. The legacy of these reforms can still be felt today, in both craft instruction and the moral value we ascribe to the work of the hand.

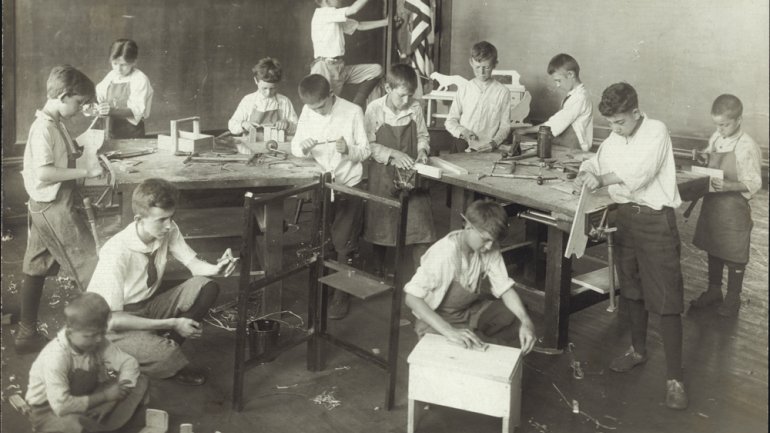

The manual training movement, as championed by Woodward, added instruction in drawing, woodworking, and metal forging to a curriculum that included Latin, mathematics, the sciences, and English composition. In 1880 Woodward opened the St. Louis Manual Training School and put into practice a three-year course of study for young men from 14 to 18 years old; it was followed soon by other manual training schools in Chicago and Toledo, Ohio. Similar to the philosophy of the manual training movement was the Swedish slöjd educational model – slöjd meaning “craft” or “hand skills” – advocated and expounded by Otto Salomon. Slöjd instructed children in the production of household goods, with an emphasis on wood, as part of their overall education; it was most notably promoted in the United States by Pauline Agassiz Shaw, who founded Boston’s North Bennet Street School in 1885.

Neither manual training nor slöjd intended to prepare students for a trade. In his writings on educational slöjd, Salomon argued that “its purpose is not to turn out carpenters, but to develop the mental, moral, and physical powers of children.” Woodward echoed that notion: “To make the production of articles the main object, and the learning of principles and methods incidental, would be to choose the shadow rather than the substance; to destroy our school by converting it into a factory." The tenets of the manual training movement became widely accepted and by the 1930s had been instituted across the United States in wood or metal shop classes and home economics courses, which, until the late 20th century, were required of middle and high school students.

Shop class altered the course of craft education in the last century, as did the GI Bill that later sent thousands of students into academic art departments and helped lead to the establishment of craft programs across the country – which expanded opportunities to teach and learn. Generations of shop students were introduced to the work of the hand without the commitment to a trade. Whether or not their manual training made them better people, the exposure to making, for craftspeople from hobbyists to masters, helped drive energy and innovation in the field of craft to the present day.

Perry A. Price is the American Craft Council director of education.