On This Land Where We Belong

On This Land Where We Belong

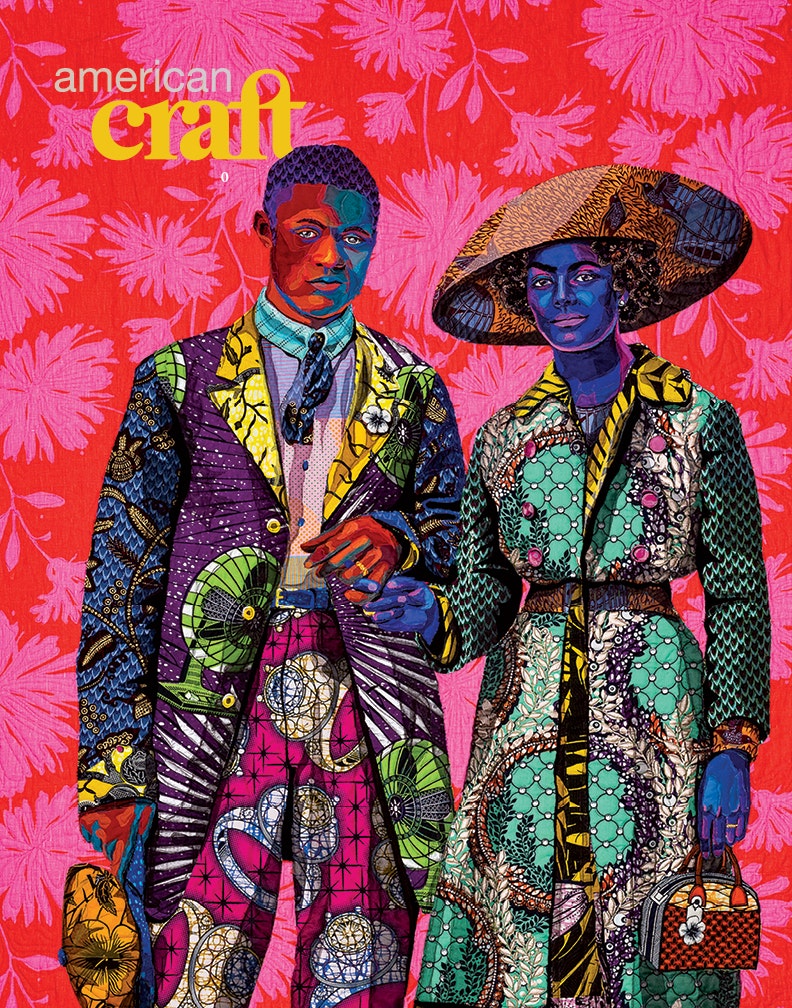

Children use stamps—featuring trees, animals, rivers, and Lake Superior—to create “kinship flags” in Shanai Matteson’s community workshops. Photos courtesy of Shanai Matteson.

“... You were a visitor, time after time

climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was the other way around.”

—Margaret Atwood, The Moment

When I learned in 2018 that a tar sands oil pipeline would be built across the Mississippi River just upstream from my hometown, I got into a car with my two young children and drove to northern Minnesota. I needed to see the exact place where they intended to lay pipe, so we followed the Great River Road from Minneapolis toward the spot designated by coordinates on a construction map: the Line 3 Mississippi River crossing. Here, the permits said a Canadian company could drill beneath the water that sustains us, creating what some have called a climate time bomb.

We stood along the roadside, soaking in the sounds, smells, and sights of riverine forests and wetlands. There was a single utility flag in the ditch—a small splash of orange against the lush green of summer, marking the place for destruction.

//

One of the most important things I’ve learned from my relationships with Indigenous people here in the occupied Dakota and Anishinaabe territories known as Minnesota is the importance of kinship to world-making.

Minnesota is a name derived from the Dakota word for water, Mni. Many people believe Minnesota means “the land of sky blue waters,” but a more accurate translation is “land where the water reflects the sky.” Even our colonial place-names reflect our broken relationships, exposing just how limited our understanding is of what it means to live in place.

To Dakota people, water is not just a resource to be extracted or managed. Water is a relative. To Anishinaabeg, land is not just property that can be bought, sold, or taken from. Earth and all the beings who reside here together are kin.

That kinship is not metaphorical.

I would never say that my mother, my daughter, or my brother are only symbolically connected. We recognize bloodlines, genetic codes, the ways we’ve nourished and guided each other, and the memories we carry between generations, some of them held deep within our bodies. We are family, capable of loving and caring for one another. Capable of keeping each other alive.

Making kin with place means widening the circle.

//

Sometimes we speak about our creative expressions or activism as our work…. What if it is not just work we are doing, but a process of making kin?

When I moved back to Palisade in 2020, I moved to an 80-acre parcel of land that had been purchased by Akiing, an Indigenous land trust and community development initiative aimed at restoring an economy rooted in Anishinaabe culture.

I am not Anishinaabe. My people came to this place from northern and eastern Europe, part of a process of colonization that is still underway. We brought with us ideas of property and control that have irrevocably altered the landscape.

Akiing is an Anishinaabe word that means “the land to which the people belong,” and last summer, this place became my home and studio. I brought with me questions about what it means to be a non-Native person living and creating from inside an Indigenous Land Back movement.

Akiing sits adjacent to the corridor where the Line 3 oil pipeline is being built across the Mississippi. Two miles away, the pipeline also crosses the Willow River on the very homestead where my grandmother was born 90 years ago.

//

If we can regard water and earth as kin, how do we reimagine the material from which we create? Fabric, dye, ink, paper. Wood or linoleum block cut for relief printing. In just one piece of textile work there are plants, insects, water, earth, and even petroleum products. And, importantly, there are stories and questions about the nature of our relationships with these.

Matteson gathered fabric and fiber from women in Minnesota Iron Range communities to create Mine/Not Mine, a quilt that’s part of the Overburden/Overlook project (collaborators include Sara Pajunen and Roopali Phadke). The material is dyed with “overburden,” the waste left by mining. Photos courtesy of Shanai Matteson

Material passes through my hands and is shaped into stories. But who belongs to whom?

//

At Akiing I began gathering material from the land and the water, and from people in my family, including my grandmothers. Though only one of them is still alive, they’ve both been wells of inspiration for crafting stories about the place I come from, about kinship, and about the movement of material through our lives.

Most of that knowledge was passed along to me in stories shared around kitchen tables, or in the process of learning how to do something with my hands. I learned to gather material and to sew from my grandmother Violet. While I was learning, I also heard from her what it meant to belong in a remote rural place, as a white-bodied person, and as a woman.

Our relationships with this land and water do not run nearly as deep as in Anishinaabeg, but in complicated and painful ways, we are woven from this land and water too.

//

Catfish, sapling, sewing needle.

Ditch bank, clear-cut, pipeline.

//

Biidwewegiizhagookwe, otherwise known as Tania Aubid, also lives at Akiing. We trudge through the woods and swamps together, sometimes up to our knees in mud. Here to fight an oil pipeline, we are also learning and teaching the landscape of family. In my case, that means revisiting settler-colonial places and stories, and looking for cracks that I can pry open to better see what is underneath. In her case, it means facing the pipeline as a survivor of genocide and displacement, continuing to create a culture of reciprocity and resistance.

As an Anishinaabe woman, she is a living expression of her ancestors’ care and commitment. In other ways, I’m an expression of mine. The problem is that one has tried to dominate and negate the other, to control the meaning of place as a means to extract. By living in my settler ancestors’ dream world of property and profit, I continue to create a nightmare for the people whom those dreams have displaced.

Fighting a pipeline means waking up each day together and radically redefining ourselves in relationship to the place where we belong. Alongside Tania and other Indigenous water protectors, I try to make kin of every bird, bee, plant, and piece of earth I touch. I don’t do this so that I can own or extract. I do this so that I might also have the inner strength and sense of purpose to resist further destruction.

//

A pipeline is being built, and in the process, a forest is being destroyed.

Activism is a creative practice, and, much like weaving or stitching together the pieces of a quilt, it takes time and patience. Sometimes the bigger picture is elusive. And sometimes it swarms to surround you.

Here, we hold material, and we shape it, while recognizing that this shaping goes both ways. Everywhere I move now, I’m surrounded by family.

//

The day Enbridge completed its Mississippi River crossing just upstream from my hometown, Tania and I stood face-to-face with police. They’d come to Anishinaabe Akiing from counties across Minnesota to protect the pipeline from protests, suppressing civil unrest with the violence of militarized law and order.

As we stood there, looking into the eyes of men who were told to remove us if we crossed an invisible line on the ground, pipe was pulled under our feet and beneath the river. “I think I’m going to be sick,” Tania whispered to me. “My knees are shaking.”

“Remember that you belong here, and I’m here with you,” I said, reaching out to hold on to her arm.

//

I repeat these words often:

You belong here.

I’m here with you.

They serve as reminders when the dominant stories take hold.

//

Sometimes we speak about our creative expressions or activism as our work, and this carries with it a sense of responsibility toward something outside ourselves. We put in the work to reap a reward, whether that be monetary or political or just recognition that we made a mark with our time here.

But what if it is not just work we are doing, but a process of making kin? What if, over time, we sow ourselves into the land, and we let it transform us? Then it would not be responsibility that binds us to places, but love born of the fact that we are alive.

What we do unto others has repercussions for ourselves and future generations too.

//

“It’s not just a responsibility to protect this place that keeps me standing here,” a friend said to me recently. He was reflecting on time he’d recently spent in jail for trespassing on land that had been stolen from his people. “It’s still a privilege to be here, resisting further destruction.”

I’ll carry his words with me now as a reminder: That kinship, belonging, and taking action out of love are all part of a creative process that’s been underway for a very long time. That there is still so much to protect.

That we are the ones who’ve been called here for that purpose.

shanai.work | @shanai_matteson

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.

This activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund.