Kitchen Heirlooms: Michael Twitty

Kitchen Heirlooms: Michael Twitty

↑ An asanka is used in Ghanaian cooking to macerate herbs, chilis, garlic, and other ingredients.

Photo: Courtesy of Michael Twitty

Last fall, American Craft introduced Object Stories, a series of pieces written by members of the craft community on the handmade objects that they cherish. In the Kitchen Table issue, we invited members of the craft and culinary communities to share stories about pieces from their kitchens and dining rooms that hold meaning to them, many of which were passed down by other generations of cooks or makers. Each story demonstrates how the objects we cook with and eat from carry vital personal, familial, and cultural history and invites readers to compliment the kitchen heirlooms in their own lives.

Story 4 of 7: Michael Twitty on culinary traditions lost and recovered

Sometimes an heirloom isn’t something passed down, it’s something you’ve lost. On my kitchen shelves in Washington, DC, is a treasure I purchased from a roadside in Ghana, a nation on the coast of West Africa, near the capital of the former Asante (uh-SHAAN-tee) Empire. It is simple, geometric, and quietly elegant. Complete with a small mortar, the grinding bowl, grooved on its insides, is known as an asanka. It is used for the mashing and macerating of fresh chilies and bulbous spices such as garlic, ginger, turmeric, and the like.

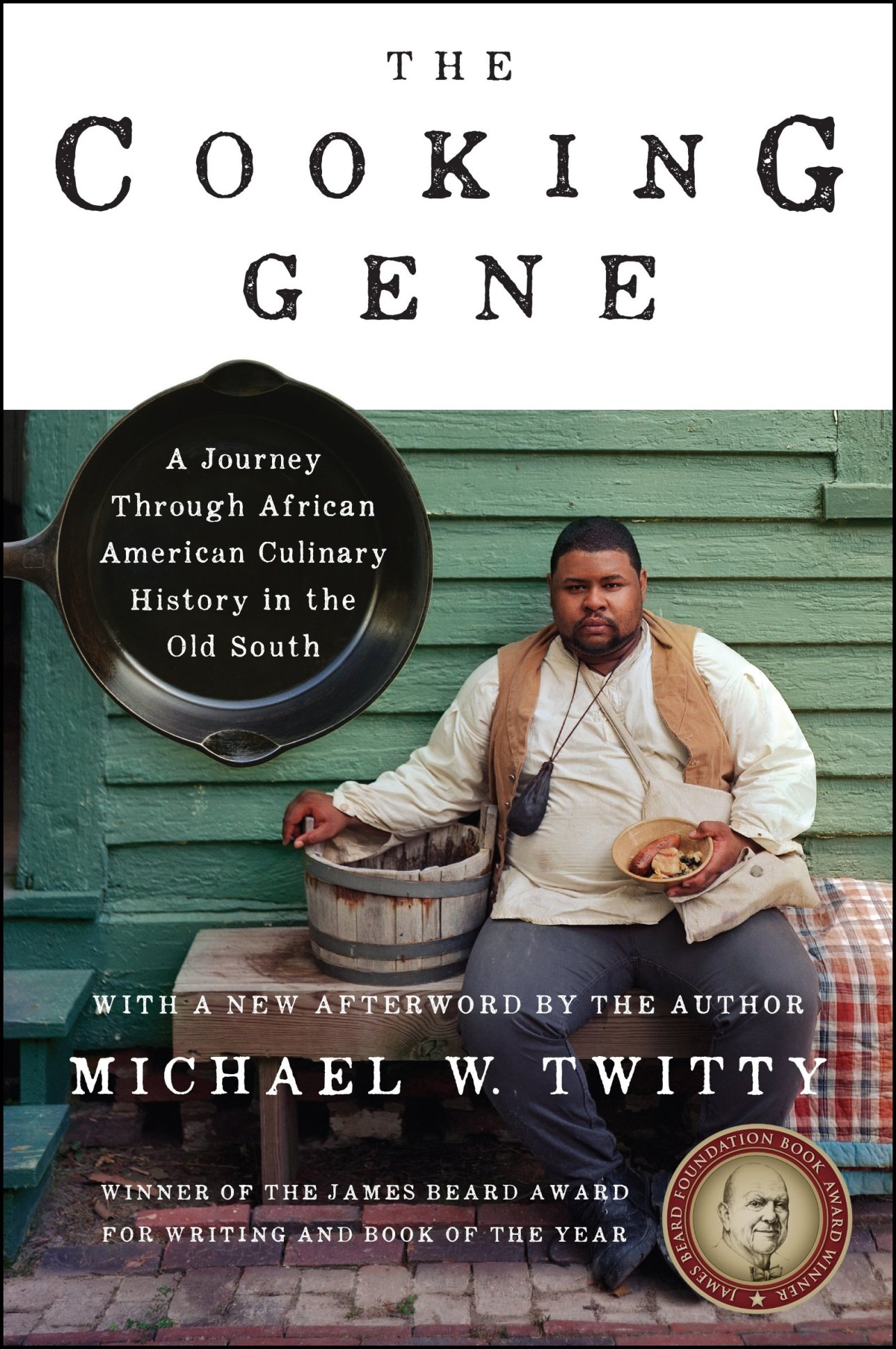

My family’s story, recounted in my 2017 food-memoir-meets-food-history The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African-American Culinary History in the Old South, helps place this heirloom recovery in its context. My ancestors were from the American South, specifically Alabama, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Georgia, and Virginia, with links to every other southern state. Most – but not all – were enslaved Africans brought through the Middle Passage from nearly every place between the modern nations of Mauritania and Senegal to Angola in the south over to Madagascar and Mozambique in the east. Although it may seem like an impossibly huge area, the traditional diet of a starch eaten with a soup, stew, or roasted or fried protein made fresh peppery condiments prepared in the asanka vital to seasoning traditional dishes to perfection.

Barbecued chicken with Jollaf rice – an example of Ghanaian cuisine. →

The brutal nature of racial chattel slavery meant the loss of human lives, stories, and artifacts key to daily life. It also meant the loss of time needed to prepare the food and the sonic environment that had surrounded my ancestors for millennia. The asanka has its own rhythm of movement – its own music, and the colors that emerge when grinding spices are beautiful. Through DNA, I have been able to trace several of my family lines to the Asante people and their neighbors. Holding this basic piece of their culinary life, grinding my own spices the way our ancient forefathers once did, has given my hearth its heart again.

Michael Twitty is a writer, culinary historian, educator, and winner of the 2018 James Beard Foundation’s awards for Writing and Book of the Year for The Cooking Gene. @thecookinggene

Thoughts on this story?

We'd love to hear from you. Send your reactions, reflections, questions, and concerns to [email protected].

Help us share impactful stories like this one

Become an American Craft Council member and support nonprofit craft publishing. You will not only receive our magazine but also help grow the number of lives craft has touched.