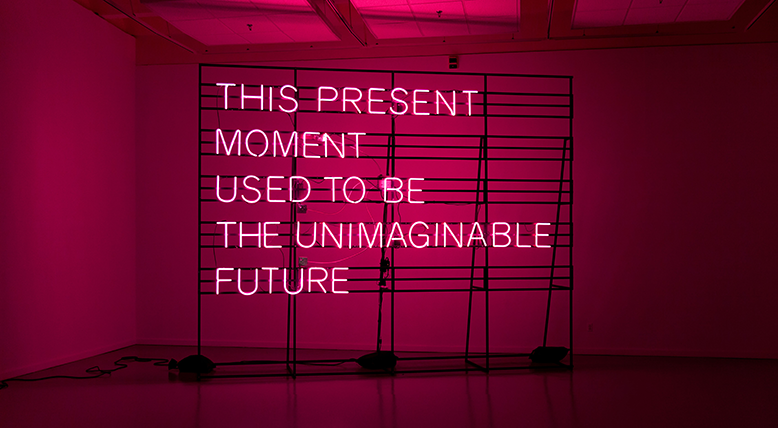

Leo Tecosky is a Brooklyn-based artist whose exquisite blown glass and neon objects and installations grow out of, and contribute to, hip hop culture. He is the first artist to systematically bring the ethos and approaches of hip hop to glass and is the only artist to have persistently and consistently applied its values to glassmaking.

What Leo Tecosky has done in his nearly 20 years of work is to show that there are so many other possibilities, so many other languages for glass. And the work is not just fresh—it’s beautiful, energizing, and powerful. In its attention to history and broad sampling, his work reflects a truly American experience of the 21st century.

Tecosky grew up during the golden age of hip hop, the late 1980s through 1990s. During this time, socially conscious hip hop artists such as Eric B. Rakim, A Tribe Called Quest, KRS-One, and others used hip hop as a way to elevate the Black self and advocate for Black liberation and social change, often with a playful approach and a positive message. The reach of hip hop went far beyond music, creating a rich culture that persists to this day in visual art and fashion, as well as a framework that emphasizes education, equity, and social justice.

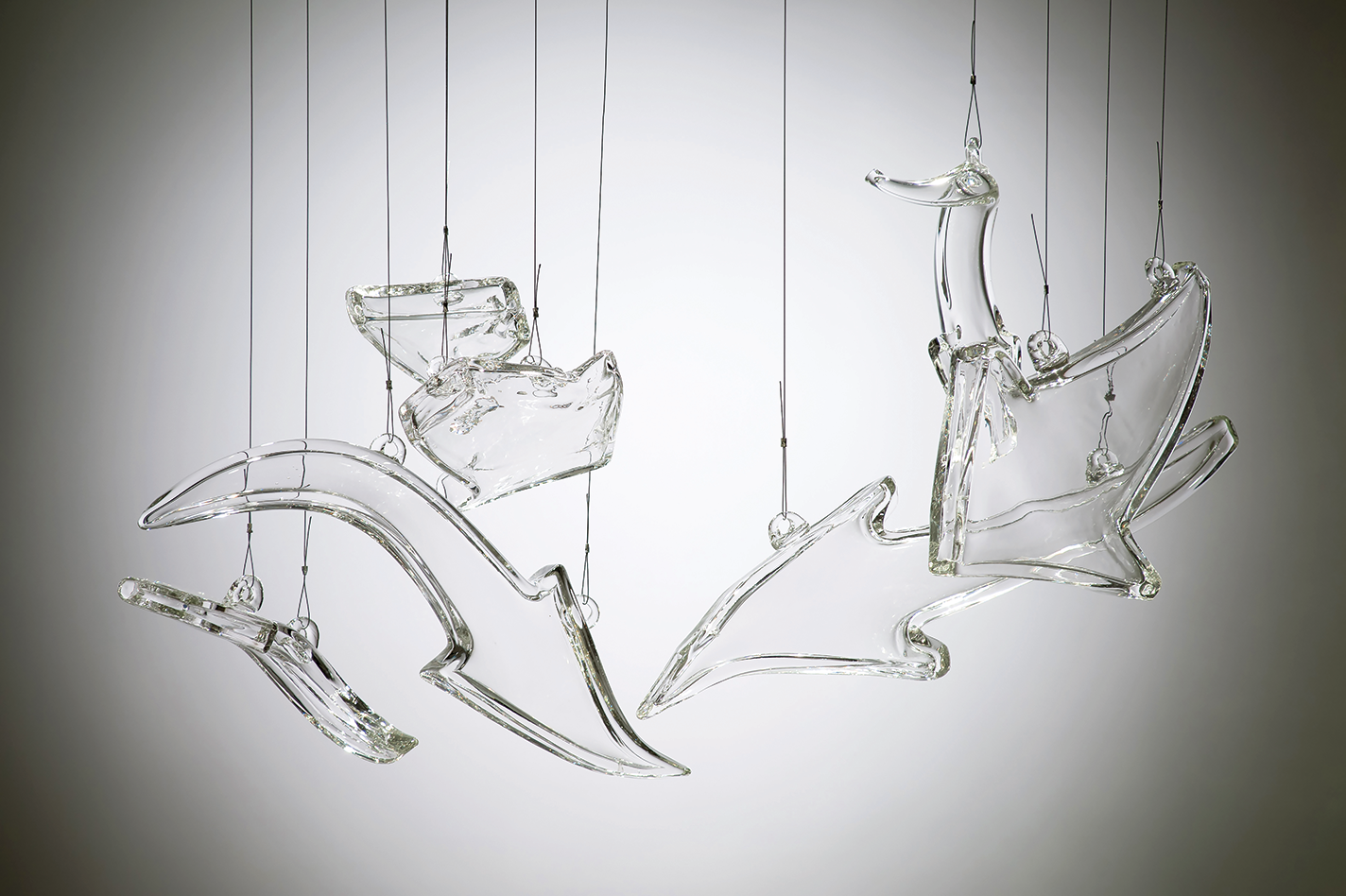

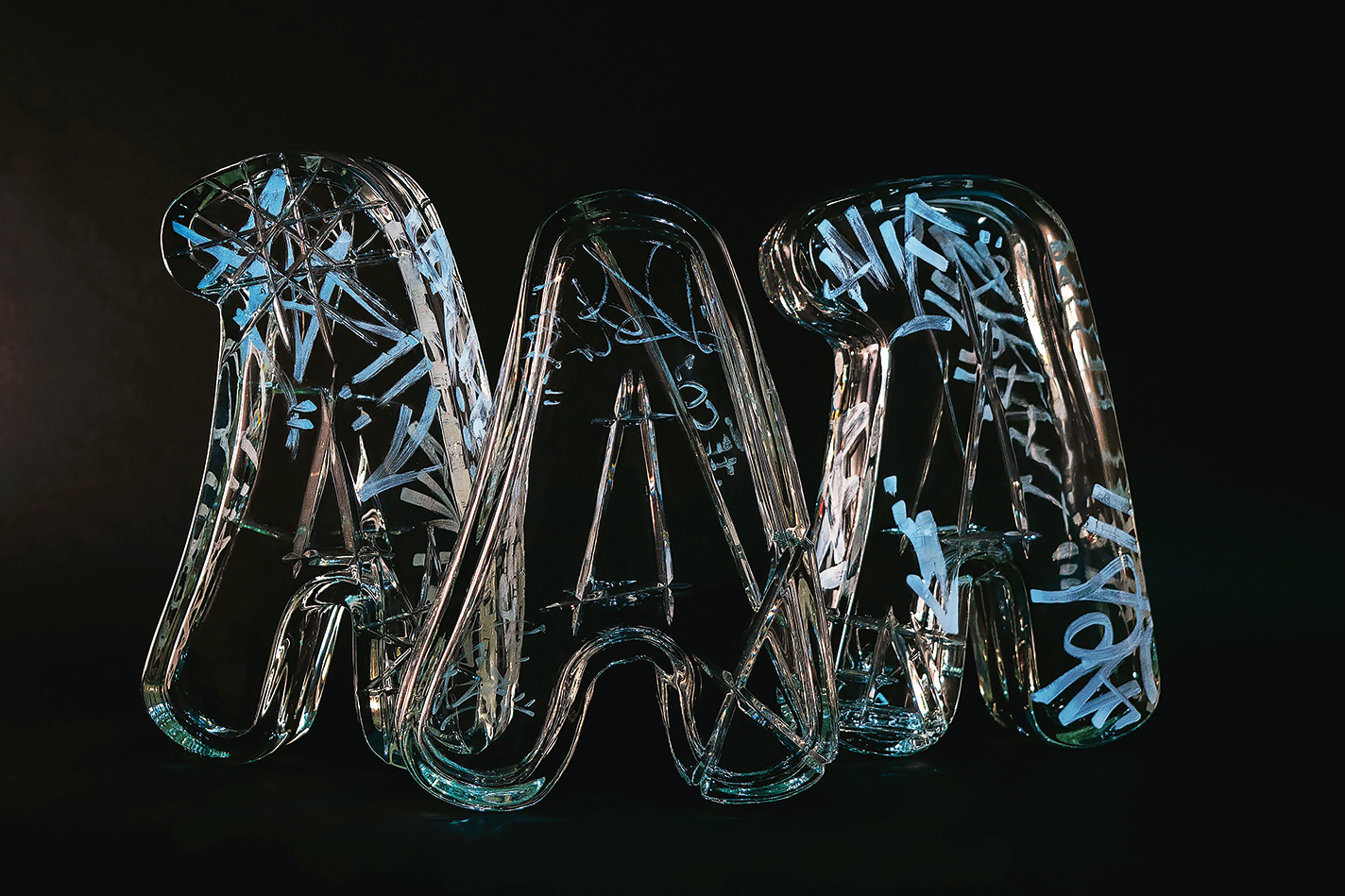

Hip hop has four main elements—DJing, MCing (aka rapping), break dancing, and graffiti—each of which requires the body to move in specific ways, to control the breath, to engage in movements that require split-second timing. Similarly, Tecosky sees the glass shop as a place of hip hop activity, given the ethos in which he creates and the physicality of making. “A lot of the way that I work,” he says, “is reminiscent of hip hop methodology, which is hot and fast or rough and ready. You get on the street and get that paint down and then go home; you can’t be on that wall forever. Glassmaking is very body-oriented in all of its processes. The glass shop is heat. It’s time. It’s the elements of gravity and temperature. And I like to think that I embody that kind of movement.”

The artist in his studio.