Crafted stories.

Every object has a maker, and every maker has a story. Discover the narratives of emerging and established artists, the evolution of their creations, and how the everyday is made more extraordinary through the fine art of craft.

You are now entering a filterable feed of Articles.

302 articles

-

![]() ACC NewsFree To Read

ACC NewsFree To ReadJoyce Lin Wins 2025 John D. Mineck Fellowship

Houston-based Joyce Lin's uncanny furniture forms have earned her a prestigious fellowship from the John D. Mineck Foundation.

Digital Only

-

![]() Free To Read

Free To ReadTreasures from the Collection

A cataloger for the American Craft Council Archives reflects on her long, strange trip through two decades of magazine back issues.

Digital Only

From the Archives -

![Nolan poses with the Japanese indigo plants in her garden.]() Free To Read

Free To ReadThe Queue: Cait Nolan

For natural dyer and quilter Cait Nolan, creation follows nature’s rhythms. In The Queue, the New Jersey–based artist discusses the cadence of her work, the power of collaboration and asking for help, and learning from an indigo-dyeing master.

Digital Only

-

![]() Free To Read

Free To Read -

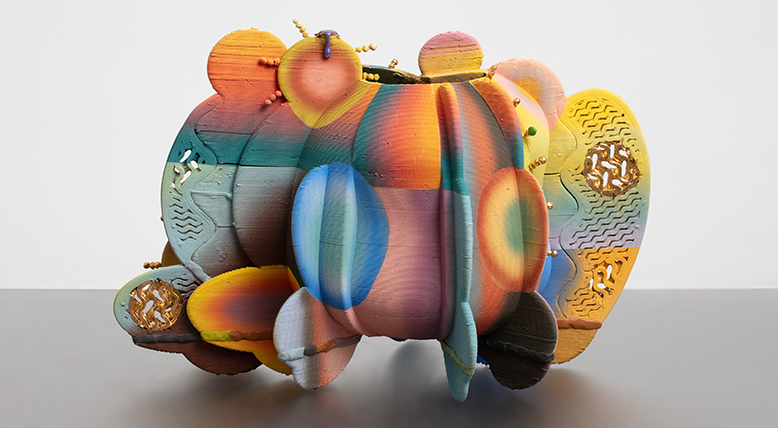

![Multicolored, multi-textured stoneware vessel]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadAnother Dimension

Ceramist Jolie Ngo is creating intricate, ebullient work that brings together craft and emerging technology.

Winter 2026

Features + Profiles -

![Large hand-dyed quilt held up in a field of grasses]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadStitched from the Soil

In a medium often focused on uniformity and speed, quiltmaker Cait Nolan relishes process, repetition, and giving back.

Winter 2026

Features + Profiles -

![]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadOut of the Elements

New York–based designer Shaina Tabak’s fecund imagination pushes materials to the brink.

Winter 2026

Features + Profiles -

![Woodworking professor and student]() MakersFree To Read

MakersFree To ReadHead and Hand

The American College of the Building Arts blends liberal arts courses and building-trades training in a four-year degree.

Winter 2026

Craft Communities -

![]() Free To Read

Free To Read

Story categories.

-

Craft Happenings

Browse a timely, curated, and frequently updated list of must-see exhibitions, shows, and other events.

-

Points of View

Essays, craft histories, ideas, analysis, and other perspectives on the significance of craft.

-

Makers

Profiles, interviews, studio tours, and videos on people who are making the world more beautiful.

-

Materials & Processes

Learn about materials and how craftspeople transform them into functional and sculptural works.

-

Handcrafted Living

Discover practical and pleasing handmade goods and stories about living with meaningful objects.

-

Travel

Explore the world of craft by visiting the places and communities where it is created and celebrated.

-

Media Hub

Discover new books, niche periodicals, videos, and podcasts—plus highlights from ACC’s archives.

-

ACC News

Explore the impact of the American Craft Council and the ACC community through stories and updates on our programs, events, artists, and more.

Take part.

Become a member of ACC.

Craft is better when we experience it together. Support makers, celebrate the handcrafted, and explore the nationwide craft community with a membership to the American Craft Council.