In 2017, on a trip to Japan with the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, architectural writer Henry Whiting encountered the work of the ceramist Shiro Tsujimura at Kou Gallery in Kyoto. He noticed in particular a vase with a pale spot on its surface (he later learned it had been masked by a small cup in the kiln). “That yellow eye kept following me as I moved around the space,” he says. “It was as if the pot chose me.”

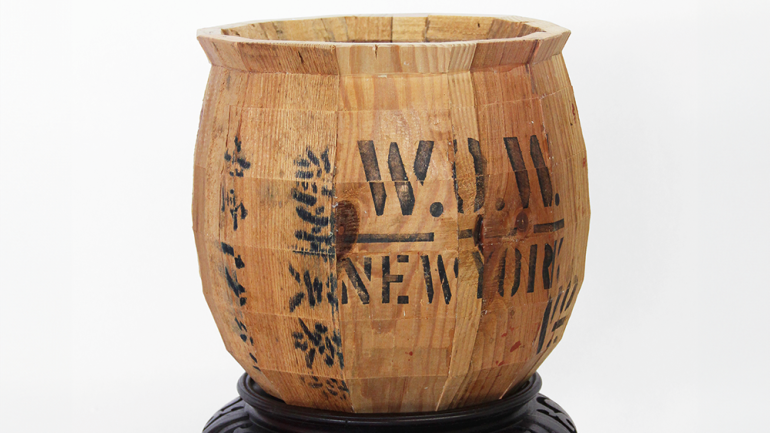

Whiting bought the pot, of course. It was the first of many by Tsujimura that he would acquire, along with the works of other Japanese potters, ranging from the young phenom Kodai Ujiie, who enlivens his work with fine inlays of polychrome lacquer, and the eminent Suzuki Goro, who has infused the venerable tradition of Oribe ware with seismic deconstructivist energy. Also in his collection are representative examples of leading American ceramists past and present, including the work of Richard DeVore, Gertrud and Otto Natzler, and Toshiko Takaezu. It’s a diverse collection that finds perfect unity at Whiting’s residence, Teater’s Knoll, a special place located in Bliss, Idaho. “The synergy between the architecture and the ceramics, something that was totally unplanned, was a revelation for me,” says Whiting.

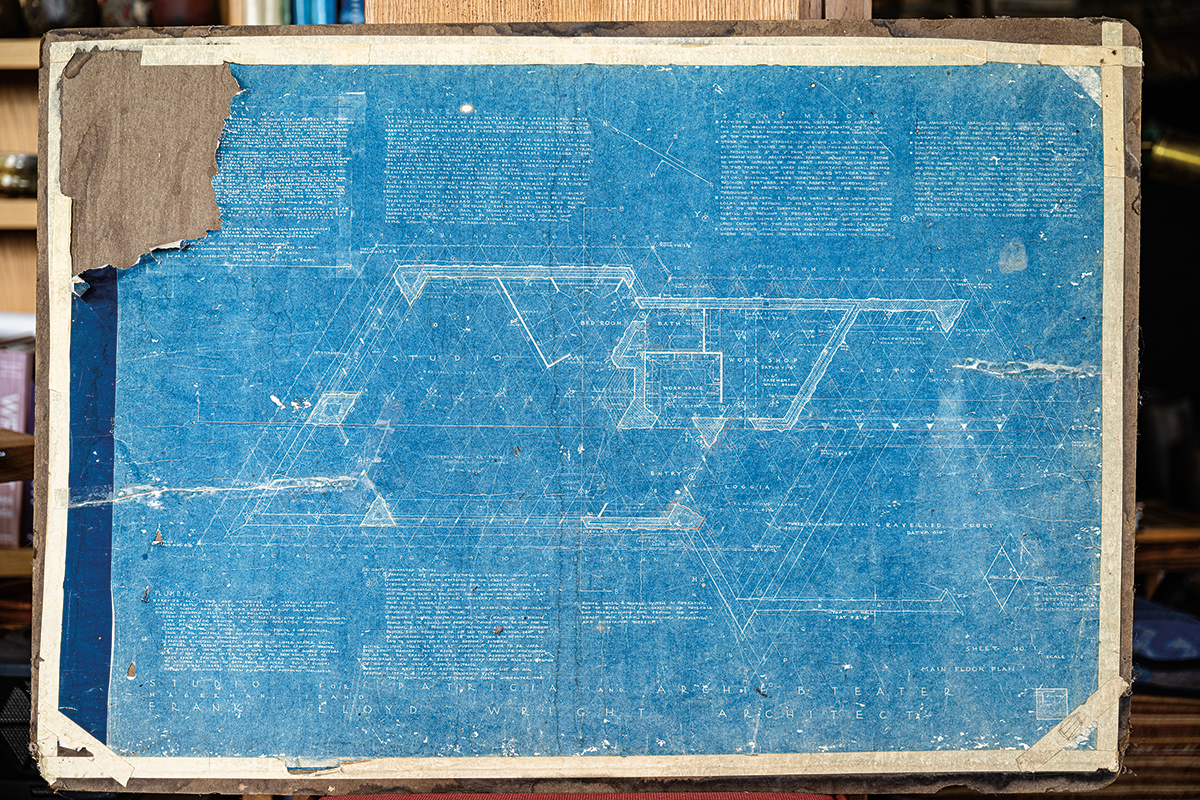

An 1,800-square-foot artist’s studio perched on a basalt cliff high above the Snake River, Teater’s Knoll is the only building in the state designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The sublimely round works by Tsujimura—inspired by storage jars from the old kilns of Korea and Japan, noble in their proportions and marvelously subtle in their coloration, each one the archaeological record of its own making and firing—are the perfect complement to the angular prow of Teater’s Knoll, which juts into the valley like a boat cresting a wave. It’s a scene one of its original owners, Archie Boyd Teater, painted many times, and never the same twice.

Teater's Knoll, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.